Editor’s Note: Nick Paton Walsh is CNN’s International Security Editor. He has reported extensively from Afghanistan for the past 15 years. The opinions in this article belong to the author.

In the end it was a sin of inattention.

For the hundreds of Afghans – crushing each other close to suffocation outside the North Gate of Kabul’s airport and holding babies in the air for US Marines to grab – the lack of regard paid to their country and the events unfolding in it has been palpable for a while now.

The US Special Immigrant Visa program to help take out Afghans and their families who worked with the US has been slow. So slow that in 2020 a federal judge called it “tortured and untenable,” ordering the Trump administration to end the processing delays.

For those in the comfort of the West, sat at their screens, inhaling deeply, and wondering why America’s longest war has collapsed with such a plughole gurgle, ask yourself: when was the last time you thought about Afghanistan? Or, as a politician spoke of it, or as a pundit, wrote or spoke about it? For the majority, it was probably only in recent days and weeks.

For the past five or six years, the US campaign in Afghanistan was about doing just enough to stop this moment from happening. To keep peace talks bumbling along. To keep the Taliban out of major cities by using precision US bombs. And to prevent a swift collapse – taking 10 days or so – into the arms of the insurgency, like the one we’ve just witnessed.

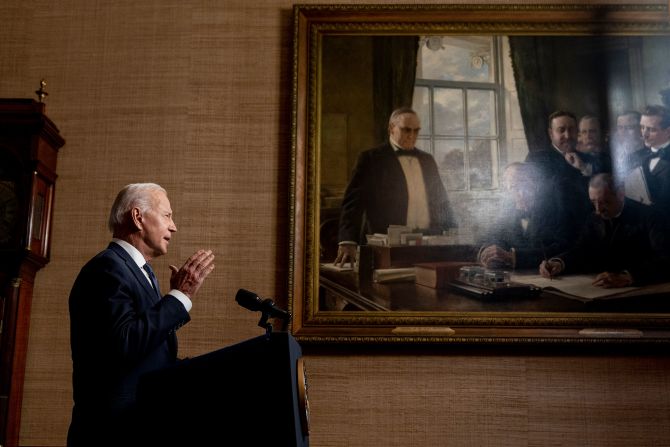

But in the background, since Barack Obama announced the US was leaving in 2014, the clock of American patience would always eventually run down to zero. As it bottomed out, the expectation was not – as President Joe Biden seems to have suggested Wednesday – that there would be chaos, like the scenes of Afghans on Monday trying to jump onto the wheels of a US Air Force plane as it taxied down the runway.

The hope was that the US public had gotten so tired of hearing about two decades of investment and promises, that Afghanistan would just fade quietly into the background. In fact, this remains the only plank of the Biden administration’s policy that may prove correct.

They were wrong about diplomatic efforts with the Taliban, about Afghan security forces holding once US forces withdrew and wrong too about former Afghan president Ashraf Ghani, who fled the country as Kabul was encircled over the weekend. But they might be right that the vast majority of Americans are not much exercised about Afghanistan.

Biden officials were actually briefing in April that the tiny numbers who opposed the withdrawal – 16% according to one April poll – meant they really could leave unconditionally. An even smaller percentage of Americans have actually served there over the past 20 years.

In pictures: Afghanistan in crisis after Taliban takeover

Afghanistan has long been a story with low American TV ratings and reader numbers. Perhaps this was present in Biden’s head when he delivered a quick and defiant speech during Monday’s afternoon news cycle. And then flew back to Camp David, where he’d spent the weekend on vacation.

But, even after this extraordinary exposition of how massive the bridge is between what America says it will do and what it can do, similar polling suggests only about a third of Americans oppose the withdrawal. About half still think it is a good idea.

Strategically, there is little doubt it is: America could not keep trying the same half-measures in Afghanistan indefinitely. But the slow-rolled visa program for the people who risked their lives to work with them, the diplomacy efforts pursued with the Taliban, and the airstrikes it continued with until Kabul fell all show that America knew where it needed to be before it left. It just never managed – or bothered – to get there.

Why did over a trillion dollars and 20 years fail to change this outcome?

I was reminded of the disconnect between America’s Afghanistan, and the real one outside the wire fences, as I witnessed the evacuation of Kabul airport this week.

The Americans working inside the base had no idea how bad it was outside the airport for the very Afghans they were there to try to get on the tarmac and to safety. Many stuck and unable to get past Taliban checkpoints. It was not the fault of those Marines – the ones processing potential evacuees – that they found themselves in that situation. But it was emblematic of how America kept the real Afghanistan often at arms-length for years.

About a decade ago, it was still normal and safe to drive to the huge US airbase of Bagram, where a large part of the American presence sat around the vast runway.

To get on, you had to coordinate which gate you had arrived at. But those outside the base – Afghan drivers and fixers without accreditation – had never been on the base to know what gate had which name to the Americans. And those Americans on the base had never been off the base for security reasons. They had no idea what we meant if we said “we are near the market. I can see a gate. Is that the place?”

The same issue endures today, as panicked Afghans try to get on to Kabul airport.

After 20 years, a fair number of the troops on the airport – sleepless, valiant and breathlessly trying – have never been to Afghanistan before, let alone outside Kabul airport.

There are Americans, American-Afghans, and former NATO soldiers, all over the world, trying to explain to people outside the base, how to get to the right people inside the base to help them. But it is hard. The Taliban are swirling nearby. Keeping the airport secure is vital to keep the planes running, and the American military evacuation machine flowing.

Even as they leave Afghanistan, the United States is really not sure what is happening outside the wire, but utterly beholden to it.