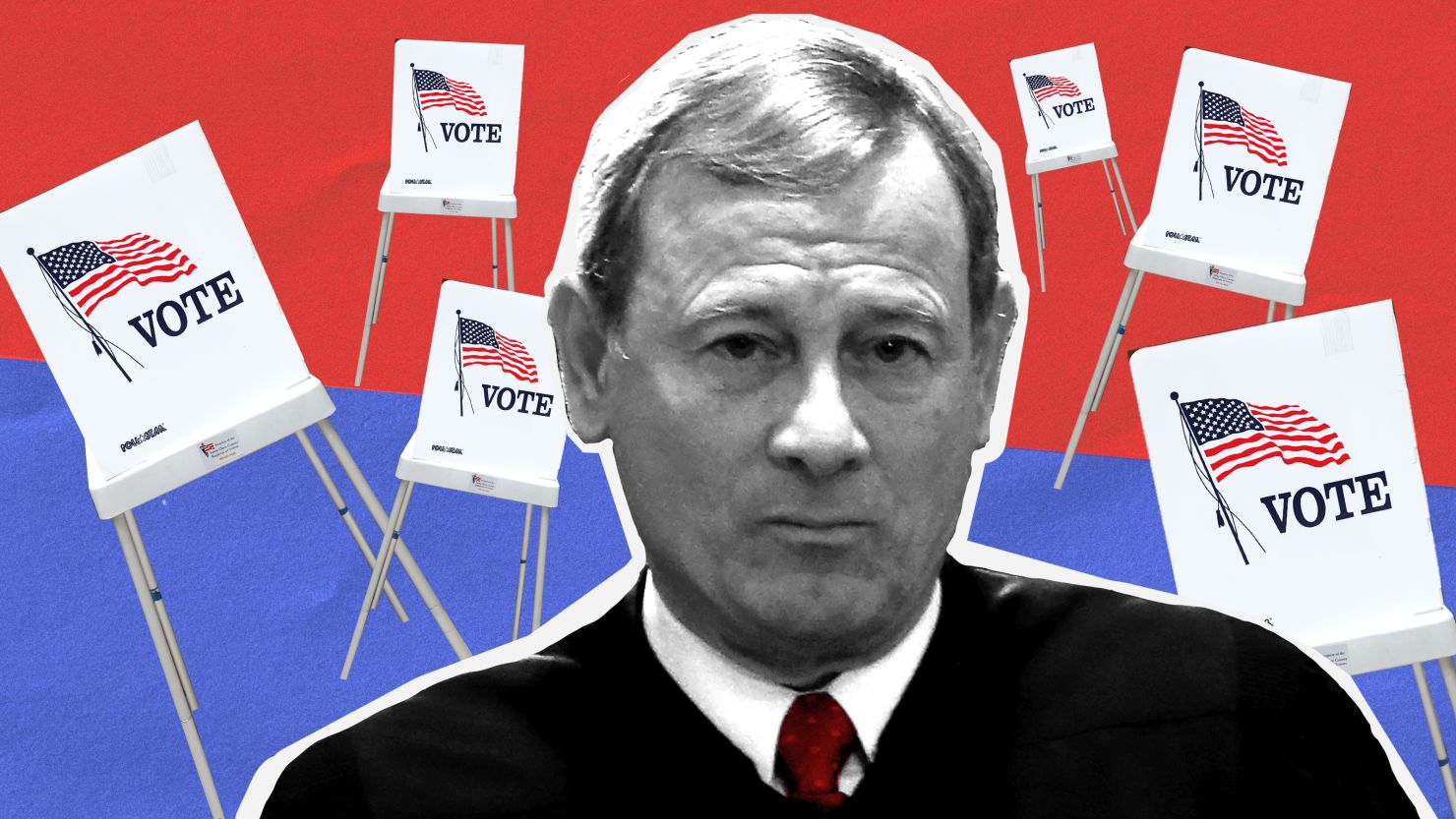

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts has hollowed out the historic Voting Rights Act, curtailed regulation of big political donors and limited challenges to partisan gerrymandering.

The final two decisions of the court session on Thursday continued this trend of Roberts’ stewardship that cuts to the heart of democracy and generally benefits conservatives over liberals, Republican voters over Democratic voters.

The pattern on voting rights traces to Roberts’ early years serving in the Ronald Reagan administration when the young GOP lawyer opposed racial remedies and argued for a constricted interpretation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

That emphasis reemerged again Thursday, just as Attorney General Merrick Garland has pointed to a “dramatic rise in state legislative actions that will make it harder for millions of citizens to cast a vote that counts.” Dissenting liberal justices on Thursday observed that “efforts to suppress the minority vote continue” yet “no one would know this from reading the majority opinion.”

RELATED: How the Supreme Court laid the path for Georgia’s new election law

The annual court session had been largely defined by incremental and often consensus moves, including to reject a third challenge to the Obama-sponsored Affordable Care Act and to compromise on a clash between LGBTQ interests and religious liberty. But the final action in two politically charged disputes showed the justices returning to predictable camps, the six Republican-appointed conservatives prevailing over the three Democratic-appointed liberals.

The Roberts Court has also sought over the years to restrain government regulation of money in politics, most notably in the 2010 Citizens United decision. And two years ago, a Roberts-led majority prevented federal courts from ever hearing challenges to extreme partisan gerrymanders, drawn by state legislators to entrench the party in power.

In the final decision of the 2020-21 term, as Roberts tossed out the California mandate that nonprofits turn over the names of major donors, the chief rejected the state’s arguments regarding anti-fraud and other law enforcement purposes.

He emphasized that “disclosure requirements can chill” First Amendment free association rights, agreeing with the challengers that donors could be dissuaded by potential public exposure. The challenges were brought by the Americans for Prosperity Foundation, affiliated with the powerful Koch family, and the Thomas More Law Center, a Christian advocacy group.

“The upshot is that California casts a dragnet for sensitive donor information from tens of thousands of charities each year, even though that information will become relevant in only a small number of cases involved filed complaints,” Roberts wrote.

Some liberal critics beyond the court said the decision in the case outside the campaign finance context could crimp political regulations and lead to more anonymous contributions, so-called dark money, in campaigns.

“Today’s analysis marks reporting and disclosure requirements with a bull’s-eye,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent. “Regulated entities who wish to avoid their obligations can do so by vaguely waving toward First Amendment ‘privacy concerns.’”

Race and election law have long split the Roberts Court and in the past, those controversies came down to 5-4 votes. But with the succession of Justice Amy Coney Barrett for the late liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg last October, the disputes fell along 6-3 conservative-liberal lines.

The three appointees of former President Donald Trump are relatively young, likely entrenching the current trend for years. Roberts, now finishing his 16th term as chief justice, is himself only 66 and based on the usual judicial tenure could serve two more decades. Senior liberal Justice Stephen Breyer is 82 years old.

Another attack on the Voting Rights Act

The Arizona case offered a new Roberts Court milestone on the breadth of the Voting Rights Act, adopted amid the nation’s epic civil rights struggles and only after the March 1965 “Bloody Sunday” attack on marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

The disputed Arizona policies required ballots cast by people at the wrong precinct to be wholly discarded and separately criminalized third-party collection of absentee ballots, for example from residents at a nursing home.

The Democratic National Committee, along with state Democrats, had argued that wide swaths of Native Americans, Latino and Black voters could be disenfranchised by the restrictions. The Republican National Committee and state Republicans defended the measures as modest steps to protect election integrity.

The two sides offered competing views of the Voting Rights Act Section 2, which bars practices that racially discriminate. Challengers can prevail if they show a practice arose from a discriminatory purpose but also if it had the “result” of denying racial minorities’ equal opportunity to participate in elections.

That latter section was at the heart of the case. A federal appeals court had ruled that both Arizona ballot rules violated that so-called “results” test, in a decision that declared, “For over a century, Arizona has repeatedly targeted its American Indian, Hispanic, and African American citizens, limiting or eliminating their ability to vote and to participate in the political process.”

Hearing the Republican appeal, the Roberts Court picked up where it left off in 2013.

That decision in Shelby County v. Holder eviscerated a separate VRA provision, known as Section 5, that demanded states with a history of discrimination obtain federal approval for any new electoral change, such as to district lines, ballot ID rules or polling operations.

Roberts had authored that 5-4 decision premised on the notion that the country no longer needed to take special steps to prevent voter discrimination based on race.

“Our country has changed,” Roberts wrote eight years ago, “and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.”

Elimination of “preclearance” generated a raft of new state ballot rules and forced voting rights advocates to rely more on Section 2 of the VRA.

On Thursday, the conservative majority said neither Arizona restriction violated the VRA as it enhanced the ability of states to defend themselves against Section 2 challenges. Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito said dissenting liberals were partly fighting the battle of eight years ago.

As the senior justice among the six in the majority, Roberts assigned the case to Alito. The two men were appointed within months of each other by President George W. Bush and have been allies on voting rights controversies.

The majority rejected the lower court’s dire assessment of the voting restrictions, stating, for example, “Having to identify one’s own polling place and then travel there to vote does not exceed the ‘usual burdens of voting.’”

Alito also rejected a focus on a voting procedure’s disparate impact on racial minorities or any “artificially magnified” differences.

“Small disparities are less likely than large ones to indicate that a system is not equally open,” Alito wrote. “To the extent that minority and non-minority groups differ with respect to employment, wealth, and education, even neutral regulations, no matter how crafted, may well result in some predictable disparities in rates of voting and noncompliance with voting rules.

“But the mere fact there is some disparity in impact does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open or that it does not give everyone an equal opportunity to vote,” Alito’s majority opinion added.

“What is tragic here,” Justice Elena Kagan asserted in her dissent for the three liberals, “is that the Court has (yet again) rewritten – in order to weaken – a statute that stands as a monument to America’s greatness, and protects against its basest impulses.”

Kagan said the majority’s approach “ignores the sweep of” the VRA objective that “minority citizens can access the electoral system as easily as whites.”

She invoked Roberts’ view in the Shelby County case that “things have changed dramatically” and then said, “Maybe some think that vote suppression is a relic of history—and so the need for a potent Section 2 has come and gone.”

But, she concluded, “Congress gets to make that call. Because it has not done so, this Court’s duty is to apply the law as it is written. The law that confronted one of this country’s most enduring wrongs; pledged to give every American, of every race, an equal chance to participate in our democracy; and now stands as the crucial tool to achieve that goal. That law, of all laws, deserves the sweep and power Congress gave it. That law, of all laws, should not be diminished by this Court.