Editor’s Note: Wrestler Navid Afkari was executed by the Iranian government on September 12, 2020. The story of his life and the movement he has inspired is being republished by CNN International to mark the anniversary of his death. This article was first published on June 28, 2021.

It was the worst news that anybody could have woken up to; as Sardar Pashaei reached for his phone one morning in September, he knew immediately that something terrible had happened.?

“When I woke at about six or seven o’clock in the morning,” he told CNN Sport, “I see a lot of phone calls from Persian television. And when I listened to the voicemail of my journalist friend, I just cried. I couldn’t control my tears.”

The Iranian Pashaei, who was the 1998 Junior 60-kilogram Greco-Roman World Wrestling champion, has been living in self-imposed exile in the US since 2009.

On that fateful morning, he learned that another Iranian wrestler, Navid Afkari, had been executed, hanged for a crime that his family and friends say he didn’t commit.?

Pashaei, who was close to Afkari’s coach in Iran, had been campaigning hard to save his life. It was a campaign that ended brutally with a hangman’s noose, but in the months since Afkari was silenced, his voice seems only to have grown louder.

An ancient sport

Wrestling is one of the oldest sports in Iran and it is one of the most popular. Ever since winning their first Olympic wrestling medal at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Iranian wrestlers have excelled at the Games, returning home with a total of 43 medals to date, more than double the haul in their next best sport – weightlifting.?

Pashaei says that there’s a wrestling gym “in every corner of every city in Iran,” and successful wrestlers there are treated differently, enjoying an elevated status in comparison to other athletes. They’re on a pedestal.?

The ancient sport is naturally aggressive and competitive, but experts say it’s a combat sport borne out of a practice to promote?inner?strength through?outer?strength.

When viewed through such a lens, wrestling might not seem too dissimilar to yoga. The spirit of wrestling is deeply engrained in Iranian culture, where it has transcended the arena of sport.

Max Fisher wrote in The Atlantic in 2012 that “The ideal practitioner is meant to embody such moral traits as kindness and humility and to defend the community against sinfulness and external threats.”?

One could argue that it was these very qualities that got Afkari executed – by his own government.?

‘He was the best one’

Afkari was born on July 22, 1993, and raised in the city of Shiraz; located in the southwest region of Iran, it’s one of the oldest cities in Ancient Persia and known to be a hotbed of poets, literature, flowers and wine.

Legend has it that the famous Syrah grape, grown as far afield as the Rh?ne Valley in France and in the new world territories of Australia, New Zealand and California, first took root in Shiraz.?

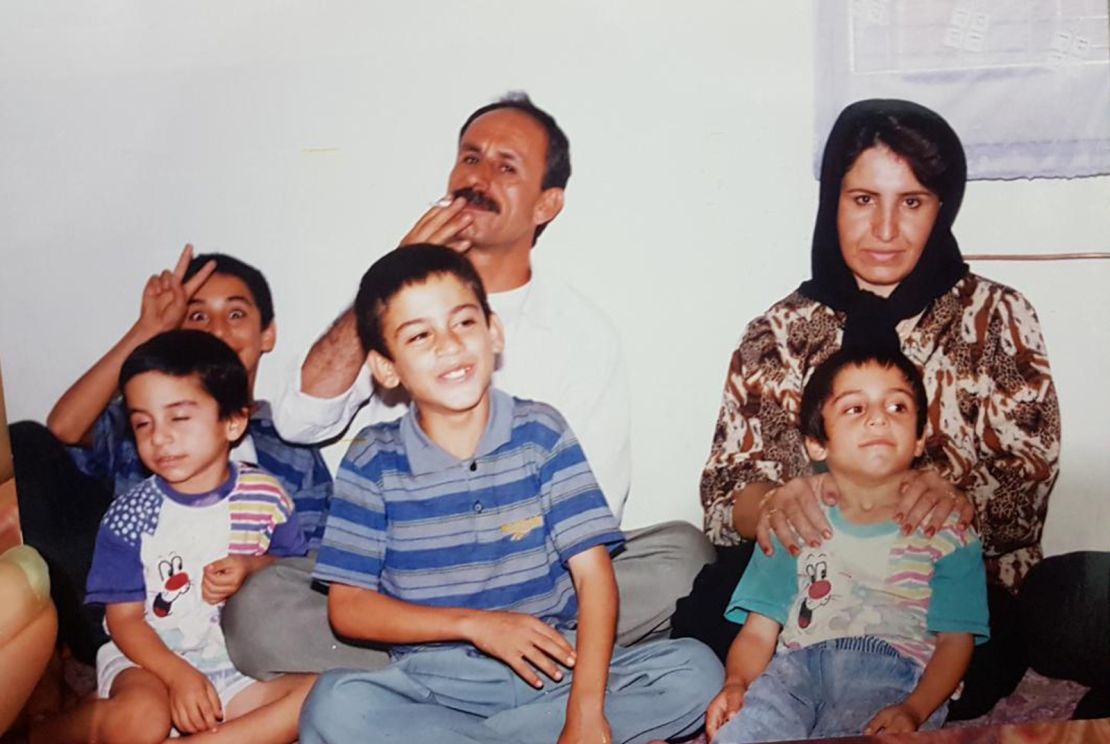

It was here that a young Afkari learned to find his way in the world. One of five children, he discovered wrestling at the age of nine and quickly dedicated his life to the sport.

By the time he was 17, he was good enough to be included in a group of eight wrestlers in the 69-kg category that attended a national training camp. Six years later, Pashaei says Afkari was ranked second in his division and on track to fulfill his dream of one day becoming an Olympic champion.?

Parents will usually try to avoid having a favorite child or revealing the truth if they do have a preference, but Afkari’s three brothers and sister knew their place in the family.

Sources close to them say that he was the apple of his mother’s eye; Afkari was successful, but modest, and he was never a burden to them.

A family member, speaking to CNN Sport only on the understanding that their identity would be protected, described Afkari as “the nicest member of the family,” adding that his friends would agree: “He was the best one.”?

Videos of him with his hands in the air, dancing and singing at home during Persian New Year, and somersaulting acrobatically into a swimming pool confirm the family’s description of Afkari as “enthusiastic, full of energy and excitement.” Such positivity would rub off on those closest to him, especially within his family.?

They say that he wasn’t particularly interested in politics, but he was keen to help out in the community, making donations and helping the poor, and he was troubled by the culture of discrimination in Iran, especially against women and those living in poverty.??

That’s why Afkari took part in the seismic demonstrations that swept through the country in 2018.

Initially, these were protests against the government’s economic policies, but they soon morphed into political opposition of the theocratic regime and its Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and were regarded as the most significant domestic challenge to the government in almost a decade.?

Afkari was concerned about rising prices in Iran, so – along with millions of others – he took to the streets to protest. His family says he was frustrated by corruption and poverty and worried that daily life was no longer affordable to many of his compatriots.?

It was a fateful decision that would end up costing him his life.?

A forced confession / A lack of evidence

According to the official version of events, Afkari killed Hassan Torkman, a water company security employee, during a protest in Shiraz on August 2, 2018.

Afkari and his brother, Vahid, were arrested a month and a half later, on September 17 according to the UN, and another brother, Habib, was rounded up later that year.

Afkari was condemned to death; Vahid and Habib received prison sentences of more than 33 and 15 years respectively and all were to be punished with 74 lashes each, according to Amnesty International.

Initially, Afkari confessed to the crime, but in court he retracted those words, arguing that he had been tortured during his interrogation by “men with hats, glasses and masks on,” and that a false confession had been forced out of him.

His supporters say that his trial was devoid of any compelling evidence, and in fact, the only video evidence available, from a closed-circuit television camera, would have been more likely to prove his innocence.

Afkari’s attorney, Hassan Younesi, told the Center for Human Rights in Iran that “There is no visual evidence of the moment of the crime, and the film presented in this case shows scenes an hour?before?the time of the murder.”

An audio recording was made in the court and leaked by human rights activists; in it, an agitated Afkari, speaking in a high-pitched voice, can be heard pleading with the judge, who seems to have little interest in giving him a fair hearing.?

Such recordings of court proceedings are extremely rare in Iran and whoever made it and released it would have done so at great personal risk.

The prosecution claimed to have video evidence of the crime committed at the specific time of 11:32 p.m., but according to the audio tape, it was never shown in court and the defendant was never able to see it for himself.

Long reads

“Why are you afraid and will not show the film?” demands Afkari. “We are not afraid of anything,” responds the judge.

On the recording, Afkari demands that his witness, Shahin Nasseri, be heard, somebody who can testify to the abuse he experienced while being held in police detention for nearly 50 days.

In a complaint filed with the judiciary in September 2019, Afkari described “the most severe and physical psychological torture,” but according to Iran’s state-run news agency, IRNA, the head of the Fars Province Judiciary rejected claims that Afkari had been beaten or tortured and, in court, he was dismissed out of hand.

“Not related. Not the time for it, sit down, don’t talk anymore!” ordered the judge on the recording. “You do not have a defense.”

The Iranian government has said repeatedly that Afkari was not tortured and that his confession wasn’t forced. CNN has asked the government if he received a fair trial, but we have not received a response.

The execution

According to the Afkari family, his final days were brutal, but there wasn’t necessarily any reason to think that the end was near.

The family says that he was kept in solitary confinement for a week and “beaten by 20 guards,” before being told that he and his brothers were being moved from the prison in Shiraz to the capital, Tehran.

That was a lie; instead, Afkari was executed on September 12th, at the age of 27.?Much later, family members learned that Vahid and Habib were in a cell close to the gallows where they had heard their brother die. ?

His body was returned to his family in the middle of the night, and they say he was denied a proper burial. The authorities had already dug a hole in the dirt and that’s where Navid was expected to be placed.

In the months that have passed since, he has hardly been able to rest in peace. The family has tried to honor Afkari, by placing a stone to inscribe in remembrance and a wall to protect it, but they say it was broken down by the authorities with a bulldozer.?

As the Afkaris tried to prevent further damage, the father was arrested, and they were cautioned that the whole site could be completely destroyed.?

As such, Afkari’s final resting place is now just a simple grave.?

His death was a crippling blow to those who had loved him and also to those who had never even met him.

So successful was the campaign to raise awareness of his plight that Dana White, the head of UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship) asked then US President Donald Trump to appeal to Iran for clemency.?

Unfortunately, though, their efforts were in vain.?

Speaking shortly after Afkari’s death in a press conference, White tried to make sense of it all but could only conclude that “he was fighting for what he believed in. And it cost him his life.”

One UFC fighter, Bobby Green, was so emotional that he could think of nothing else after beating Alan Patrick in Las Vegas.

Green, who was a wrestler himself before turning to Mixed Martial Arts, cut short his post-fight interview by saying, “Somebody just lost their life for protesting; that just messed me up. I thought we were going to be able to save him. That is so sad, it broke my heart. I don’t even want to talk right now.”

Inciting a culture of fear

Afkari was one of at least 267 people who were executed in Iran in 2020.

A report compiled by Iran Human Rights and advocacy group Together Against the Death Penalty (ECPM) concluded that Iran can boast of the highest number of confirmed executions in the world per capita, and that The Islamic Republic uses executions “as a tool to oppress political dissidents, including protesting citizens, ethnic minorities and journalists.”

IHR’s director Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam explained that the regime creates fear through the death penalty to maintain power, but that fear is now waning.

“Protests in recent years,” he said in the report, “have shown that not only are people losing their sense of fear but they are also uniting in their anger against these executions.”

While still grieving, Afkari’s friends and family are dealing with further intimidation.

His former coach,?Mohammad Ali Chamiani, says he has been warned not to talk about him, and just in case there is any misunderstanding, he’s been banned from teaching wrestling, sacked by his gym and stripped of his benefits and insurance.?

It’s a humiliating end to Ali Chamiani’s career; until recently, he was revered, considered on three separate occasions to be the top wrestling coach in the country.

The family is now concerned for the safety of their other sons in prison but they say that Afkari has prepared them to be strong.

Throughout the two years that he was imprisoned, family members say he was building them up, allaying their fears where possible and ensuring that they’d be able to continue his struggle when he was gone.

He knew that he was going to be put to death, but in his last night alive, his family says he called them to say that he was doing OK, asking them not to worry.

United for Navid

Afkari may be gone, but his voice is now louder than ever. The recording of him defiantly challenging the judge can be found all over social media, so, too, an audio recording that he made while he was in jail.?

“During all the years that I wrestled,” he states calmly, “I never faced a cowardly opponent who played dirty because wrestling is an inherently honorable sport. But it’s been two years that my family and I have had to face off against injustice and the most cowardly and dishonorable opponent.”

Upon realizing that his legal challenge was destined to fail, he concluded, “They are just looking for a neck to throw their noose around.”

One of his most prominent supporters is Masih Alinejad, an exiled Iranian journalist, author and political activist, who’s now living in New York.?

She never met Afkari, but she later learned that he had reached out to her during the protests.?

On February 12, 2018, Alinejad had posted an image on Instagram of an Iranian woman who’d been arrested for protesting the compulsory headscarf (Hijab) law.

Among the list of 1,648 comments was one from Afkari, whose public courage and audacity would have been inconceivable to many in Iran.

In Farsi, he posted a direct attack on the Supreme Leader, a line which translates to “I spit on your rotten soul.” Alinejad’s original post received over 71,000 likes and could have been seen by any of her five million followers.?

Alinejad told CNN that it was Afkari’s brief comment, quickly lost in the sea of social media, that has posthumously formed such an unbreakable bond between them.

“I was shocked at how brave he was,” she told CNN Sport. “He cursed the Supreme Leader of Iran, in public, under his own name. That is why I care so much about Navid. That actually breaks my heart. I did my best, but sometimes I feel miserable and frustrated that we couldn’t save him.

“We have so many Navids now fighting for freedom,” Alinejad explained, “fighting for equality, fighting for justice, fighting for dignity, fighting to have a normal life, fighting to get rid of dictatorship.”?

Tokyo 2020

Alinejad believes that the government viewed Afkari as a threat and moved quickly to silence him, using his execution as a deterrent to others, adding, “His only crime was just joining Iran protests and that scares the government. The government actually wanted to create fear within the society.”

But his execution might prove to have been a miscalculation; it may have backfired.?

Alinejad is the?campaign founder?of United for Navid, an action group that is keeping his voice alive.

Afkari’s sacrifice has motivated many Iranian athletes to find the courage to step up and speak out; while some want politics to be separated from sport in their country, all agree on the need for even greater reforms.

She understands the risks that many of them are taking.

“Sometimes, when you keep silent, they can execute you. Sometimes, when you speak up, they can execute you. So that is why we have to do something beyond just talking about Navid, talking about his goal. He wanted to have greater freedom. He wanted to have a better country [in which] to live.”

The execution ended the life of Afkari, but it has failed to silence his voice. He continues speaking from beyond the grave: “If there’s one thing I learned from stepping onto the wrestling mat,” he was recorded saying in jail, “it’s that I should never give into oppression and lies.”

That spirit seems to be alive in his family; despite enormous pressure to comply with the government and blacken Afkari’s name, they are standing firm.

“We care about the good thing that we have to do. We care about our goal, rather than think about the tortures and fear,” said his relative, adding that Afkari’s mother is torn between conflicting emotions.

“She has two feelings right now. She’s so sad for losing Navid. And secondly, she’s so proud of Navid because she knows that Navid chose the right path.”?

Afkari has become larger in death than he ever was in life. Pashaei concludes that the campaign of which he is a spokesman is now an unstoppable force.

“They thought that by killing this guy, they can bury his name like his body. But it never happened. Now, we see that he’s a champ. He’s a hero for millions of young athletes. He’s everywhere now.”