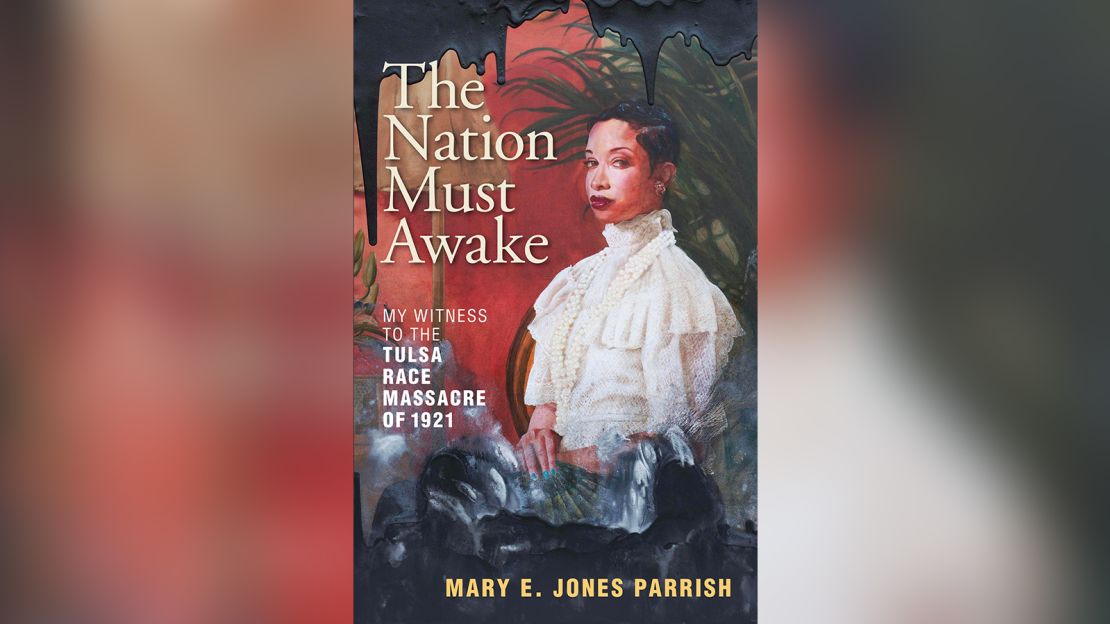

Editor’s Note: Anneliese M. Bruner is a Washington, DC-based writer and editor. She is the great-granddaughter of Mary E. Jones Parrish, a survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre whose account of the event, “The Nation Must Awake: My Witness to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921,” has been reissued by Trinity University Press with an afterword by Bruner. The views expressed here are the author’s own. View more opinion on CNN.

Pushing a preferred storyline to uphold a system that favors the powerful is at the heart of any effort to rewrite history. But creating false public narratives is the purview of authoritarians.

This a standard game, but many Americans are still just waking up to it. My great-grandmother Mary E. Jones Parrish understood this dynamic all too well. She was a trained journalist and teacher who moved to Tulsa around 1919 and was reading at home when the violence began on May 31, 1921. Her young daughter, my grandmother Florence Mary, called her to the window, saying: “I see men with guns.”

In her newly republished book-length account of the Tulsa massacre of 1921, my great-grandmother reported on the horrific events that she and her daughter escaped. She admonished the nation to awake to the factors that feed state-sanctioned violence and provided a model for capturing and preserving the truth. She knew, as did the other survivors of the massacre: Our democracy depends on it. She wrote: “The rich man of power and the fat politician who have maneuvered to get into office, and even our Congress, may sit idly by with folded hands and say, ‘What can we do?’ Let me warn you that the time is fast approaching when you will want to do something and it will be too late.”

The truth our democracy requires is fighting its way to the light. Earlier this month, “Mother” Viola Fletcher, 107, the oldest living survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre, testified before Congress about what she witnessed on May 31, as a mob of White Tulsans rampaged through her neighborhood killing Black people, looting and torching their homes and businesses. With a calm demeanor that belied the terror she recounted, she told the story of her family fleeing in the middle of the night to escape violence sweeping the Greenwood quarter: “The night of the massacre, I was awakened by my family – my parents and five siblings were there – I was told we had to leave and that was it … I will never forget the violence of the White mob when we left our home. I still see Black men being shot. I still see Black bodies lying in the street.”

Hearing the excruciating details of what she saw as a child of seven was not the only shock for viewers – and it wasn’t at all a shock to me. “For 70 years, the City of Tulsa and its Chamber of Commerce told us that the massacre didn’t happen, like we didn’t see it with our own eyes,” she said, revealing the complicity of local government and businesses in covering up the crimes of 1921. City officials were not keen to acknowledge what happened because of how it would look to the outside world and imposed their self serving agenda of denialism on the victimized community, without regard for the people’s suffering. Evidence that city fathers, along with the National Guard, bore some responsibility for the destruction provided another motive for official eagerness to suppress the truth.

A week before Mother Fletcher testified, another denial of truth was unfolding within the same halls of power. The House Oversight and Reform Committee held hearings on the Jan. 6 invasion of the US Capitol, during which Georgia Rep. Andrew Clyde told his colleagues, “Watching the TV footage of those who entered the Capitol and walked through Statuary Hall showed people in an orderly fashion staying between the stanchions and ropes taking videos and pictures. You know, if you didn’t know the TV footage was a video from January the sixth, you’d actually think it was a normal tourist visit.”

He and other like-minded lawmakers oppose the establishment of a commission to investigate the unprecedented attack, downplaying the gravity of an event that some have referred to as a failed coup d’etat. They are working feverishly to characterize the attack as relatively benign and to cast doubt on the legitimacy on any commission that is empaneled to investigate the crimes that took place in Washington, DC – the city where I reside – on Jan. 6.

Some others who lived through the attack on the Capitol see it differently. On Feb. 23, former US Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund testified before the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration and the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee: “The events on January 6, 2021, constituted the worst attack on law enforcement that I have seen in my entire career. This was an attack that we are learning was pre-planned and involved participants from a number of states who came well equipped, coordinated and prepared to carry out a violent insurrection at the United States Capitol. I witnessed insurgents beating police officers with fists, pipes, sticks, bats, metal barricades and flag poles. These criminals came prepared for war. They came with weapons, chemical munitions and explosives. They came with shields, ballistic protection and tactical gear. They came with their own radio system to coordinate the attack, as well as climbing gear and other equipment to defeat the Capitol’s security features.”

Another law enforcement officer, Metropolitan Police Department Officer Michael Fanone has gained fame for his condemnation of attempts by some lawmakers to sanitize what happened that day. “It’s been very difficult seeing elected officials and other officials kind of whitewash the events of that day or downplay what happened,” he told CNN’s Don Lemon, adding, “I experienced a group of individuals that were trying to kill me to accomplish their goal.”

In each of these scenarios, authority for bringing to light what happened and who was responsible rests, paradoxically, with stakeholders whose interests align with suppressing a factual accounting. In Tulsa, city fathers were more concerned with their image than in ensuring justice for the victims. And in Congress, what could be complicit factions among lawmakers are thwarting efforts to ensure transparency in government, a hallmark of a healthy democracy, to maintain power and escape possible criminal prosecution.

Their lust for power is matched by the bloodlust that Mary Parrish saw in the Tulsa mobs. She wrote: “This spirit of destruction, like that of mob violence when it is once kindled, has no measure or bounds.”

In a conversation I had with renowned historian Scott Ellsworth, who has been studying and writing about the Tulsa Race Massacre since the 1970s, I recall him using that same word – bloodlust – to describe what eyewitnesses said the Tulsa attackers exhibited. That was the motivating force for the murderous mob to organize and resume the attack on Greenwood, deploying the machinery and methods of war. It’s what we can see in the eyes of those who marched in Charlottesville, carrying torches and shouting “Jews will not replace us.” It’s what we can hear in the voices of those screaming as they slammed their bodies and weapons into the US Capitol.

Looking back on the events of 1921 and how we dissect and analyze what happened, it feels strange to think that people 100 years from today will evaluate the way we handled the political turmoil and violence in which we are currently embroiled. Will we demand truth and accountability, or will we accept a watered-down investigation that does not make people answer for potential crimes?

Mary Parrish’s warning is clear that failing to hold those responsible for political violence will beget further violence and destruction, perhaps even of democracy itself. I hope that we pass muster.