Tiny particles recovered from the summit of a mountain in Antarctica are clues that a meteorite more than 100 yards wide exploded in the sky 430,000 years ago, sending a fireball of vaporized extraterrestrial material to the icy surface, according to new research.

Such “airbursts” are thought to occur more frequently than fallingmeteors or much larger asteroids that leave craters in the ground – such as the one that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Identifying these space rocks, however, is much harder because they leave few traces in the geological record.

“Asteroids must be sufficiently massive to make it through the atmosphere and reach the ground with enough speed to form an impact crater. Smaller objects, which are much more abundant, explode in the atmosphere and do not form a crater,” said Mark Boslough, a researcher at the University of New Mexico, who has studied meteorite explosions but wasn’t involved in this latest study.

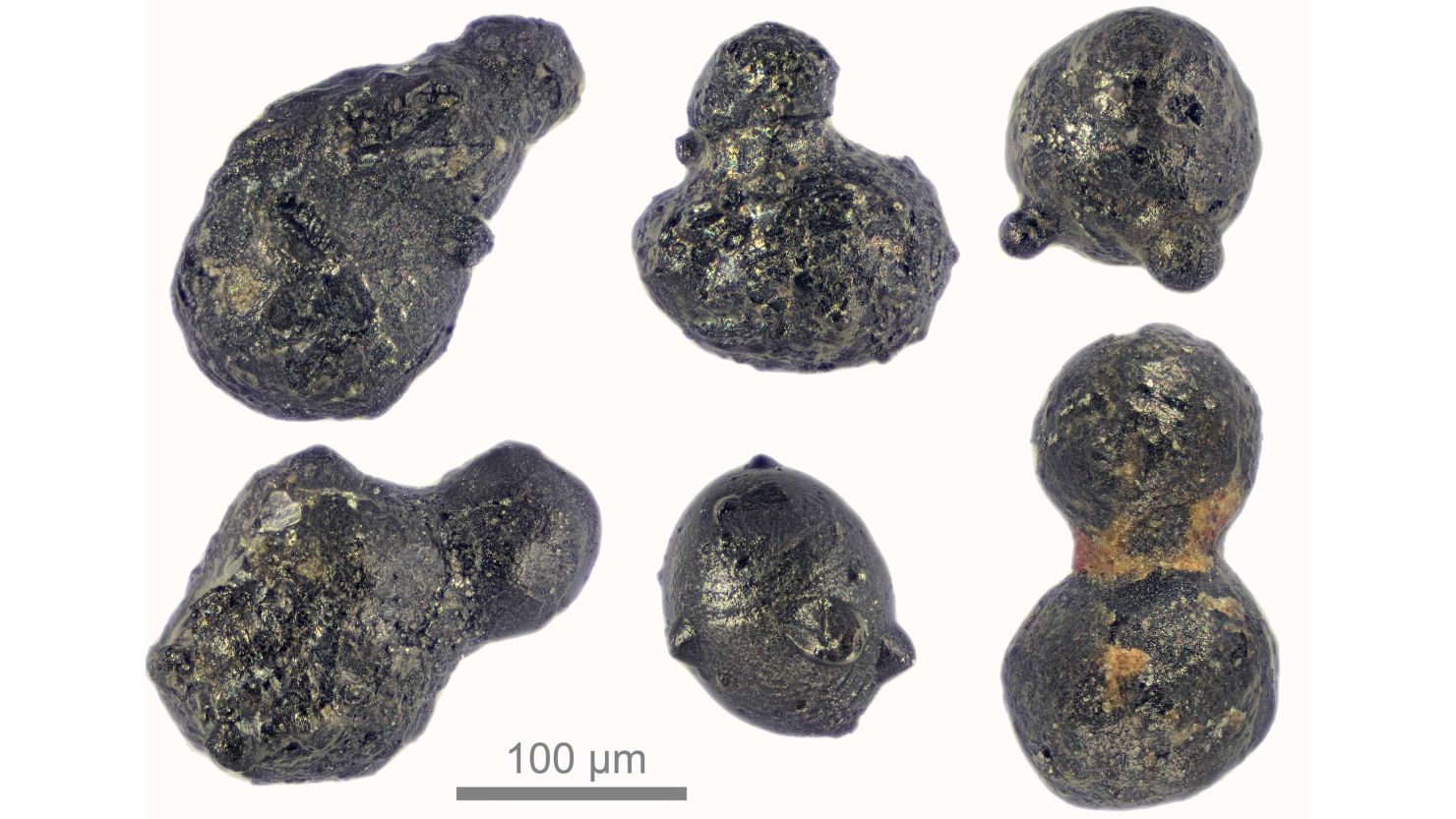

Matthias van Ginneken, a research associate from the University of Kent’s School of Physical Sciences, collected the 17 dark black particles – all smaller than 1 millimeter and invisible to the naked eye – while on an expedition to the S?r Rondane Mountains, Queen Maud Land, in East Antarctica, where the Belgian Princess Elisabeth Antarctica station is based.

“I first noticed that some of them looked like they had been stuck together, which would have had to have happened when they were molten. It would have meant lots of them interacting with each other when they were at a very high temperature. The only sensible way to explain this was a huge impact,” said van Ginneken, the lead author of the study that published in the journal Science Advances on Wednesday.

‘Touchdown impact’

He and a team of international scientists were able to piece together what happened when the ancient meteorite entered the Earth’s atmosphere by analyzing the microscopic particles. Their chemistry and high nickel content suggested they originated in outer space.

The researchers compared them with similar particles found in two cores of ice, which serve as archives of past geological conditions. The samples, dated to 430,000 years ago, were taken from other locations in East Antarctica. Numerical modeling looking at the distribution and density of the particles suggested that the meteorite would have been between 100 meters and 150 meters wide.

While the meteorite didn’t create a crater, it would have wreaked havoc on the ground.

“It was a touchdown impact. Like an explosion in the atmosphere that’s creating this very hot cloud of gas that travels very fast toward the ground,” van Ginneken said.

He said if a meteor event like that took place above a densely populated area, it would result in millions of casualties and severe damage over distances of up to hundreds of miles.

There are eyewitness accounts for two smaller but more recent airbursts – although in both cases no fireball made contact with the Earth’s surface.

An asteroid entered Earth’s atmosphere over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013. The rock exploded in the air, generating brightness greater than the sun. The asteroid damaged more than 7,000 buildings and injured more than 1,000 people. The shock wave broke windows 58 miles away. It had gone undetected because the asteroid came from the same direction and path as the sun.

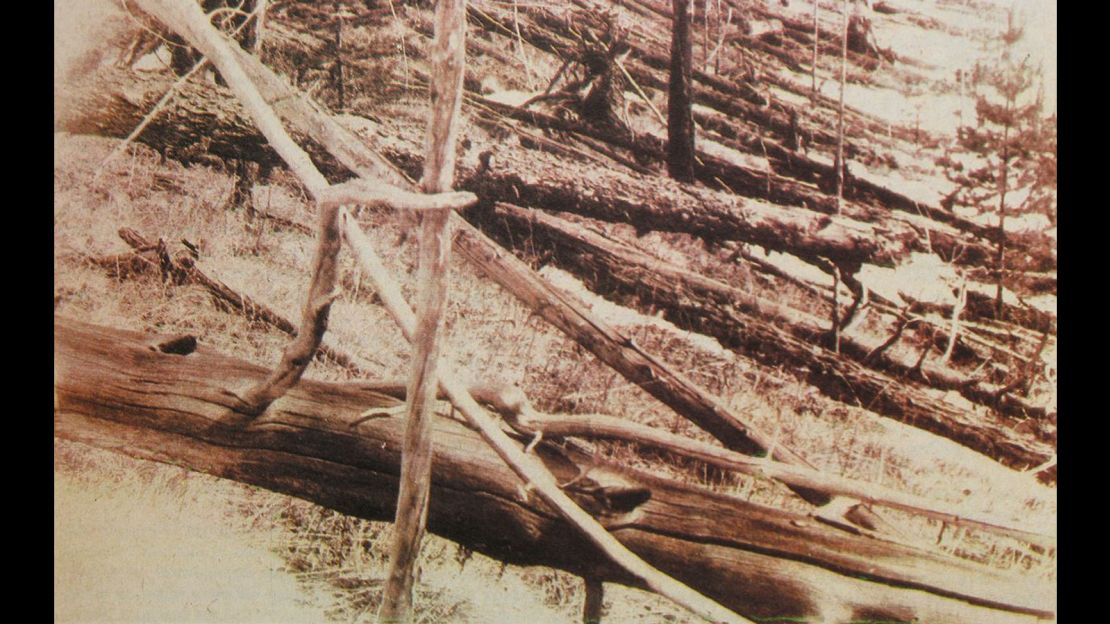

It’s believed a powerful asteroid struck the Podkamennaya Tunguska River area in a remote Siberian forest of Russia in 1908 – although the idea was viewed as far-fetched at the time. The event leveled trees and destroyed forests across 770 square miles (1,200 square kilometers), an area nearly three-quarters the size of the US state of Rhode Island. The impact threw people to the ground in a town 40 miles away.

Boslough, the University of New Mexico researcher who wasn’t involved with this study but has studied the Chelyabinsk meteorite explosion, said the paper provided good evidence of the meteorite airburst over Antarctica 430,000 years ago.

“The details of what happened were inferred from the structure, shape, chemistry, and mineralogy of the particles. There are no other processes we know of that could form them,” he said.

“Therefore airburst events happen much more often than cratering events. The geological evidence for an airburst is not as obvious as that for a solid impact, but this paper makes a strong case.”

Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory newsletter: Sign up and explore the universe with weekly news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.