Editor’s Note: David M. Perry is a journalist and historian. He is senior academic adviser in the history department of the University of Minnesota. Follow him on Twitter. The views expressed here are those of the author. View more opinion articles on CNN.

My father-in-law died last week. He didn’t have Covid. He had terminal lung cancer that spread through his body, and at the end experienced severe delirium and fluid in his lungs.

He was one of eight kids and because we knew his death was coming, the family wanted to do what they always do at difficult times like this: descend on the hospital en masse, raucous and sad, and most of all together. In the past, when mourning, they would hold big Lutheran funerals (with hotdish, meatballs, and yes, funeral potatoes). My family is smaller and not-at-all Lutheran, but when my mother was dying a few years ago, people traveled from around the country and we gathered around her in the hospice as her final weeks passed. Even the day after she slipped from consciousness, two more friends flew in from the East Coast, and we sat close, crying, but together. Those memories carry me today as I still wrestle with her loss.

On Thursday, ten of us get to stand outside in sub-zero weather for 15 minutes at a military graveyard as soldiers fire a salute and play taps. Then we’ll scatter back into the Minnesota winter.

We are left with the cold fact of imminent death surging throughout this brutal winter, without access to any of the rituals that might make it more bearable.

For obvious reasons, all of us have been focused on the direct human cost of the pandemic, with more than 470,000 dead in the United States alone. But that number, even as it rises, drastically underestimates the scale of the disaster when it comes to mortality and grief. That’s because the experience of pretty much every person touched by any single death for any cause – in the US that’s over 3 million last year – has also been shaped by Covid. The pandemic forces us to sever the connections that can enable us to endure grief. What it takes to stay safe is to close off the pathways that lead to healing.

The crisis of the pandemic operates on a titanic scale. It’s nearly impossible for me to get my mind around the numbers of people dying, those suffering from long-haul Covid effects, the sweeping malign economic consequences, the widening inequalities that will linger for years. There’s just so much weight from month after month of strangeness and fear.

But if anything, even this scope is looking too small, somehow underselling the true breadth of the catastrophe. We’re now just over a year since the first confirmed Covid-19 death in America, but nowhere near the end of the pandemic. My family is reeling from our loss, one death reverberating among dozens of friends and family members. But communal grieving, and hopefully healing, may not really be possible until this summer or even next year. The road ahead is still grim and too solitary.

One analysis from last summer found that for each death from Covid, nine people experienced bereavement (which comes with associated mental and physical health problems). The ways in which Covid keeps us from the rituals of mourning nearly every death, no matter how expected or peaceful, means that each loss potentially likewise multiplies bereavement. If one expands that lens to include not only those who perished from Covid but anyone whose grieving process has been altered by it, and that number explodes to over 460,000 times nine; it becomes unfathomable.

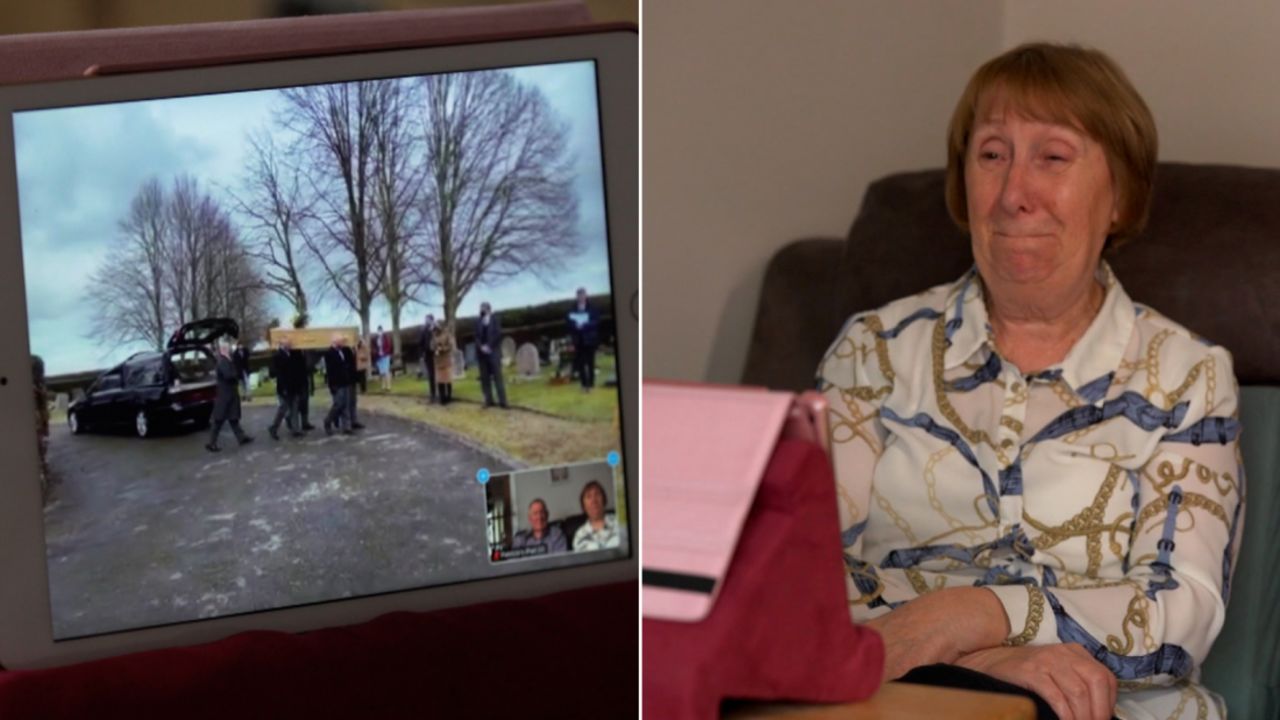

Too many people have died alone, accompanied only by a view screen, or at most one or two family members. Zoom funerals do not replace hotdish, potatoes and laughter.

There’s a reason that societies develop rituals to help us process the loss of life and, of course, there have always been reasons that funerals and memorials get delayed or canceled all together. But certainly during my lifetime, there’s never been such a relatively total shutdown of our rituals, secular and sacred, formal and informal, somber and filled with whiskey-fueled revelry. That level of trauma will not pass soon for most of us, certainly not without recognizing it and doing the work to address the pain, even if we do manage to gather for memorials and funerals in the (hopefully) post-Covid years ahead.

Our mental health systems aren’t ready. Our spiritual leaders may not be ready either. We’ll have to be proactive both in building capacity to support mourning and encouraging people to take care of themselves in an era of post-Covid trauma.

It’s not just about health and guidance though; there’s also bureaucracy. The shape of most of our lives does not permit a long and retroactive wave of memorials and wakes and funeral masses and the other rituals that soothe the pain of loss. We already struggle in our work-life culture to gain time away for bereavement, operating in managed human resource systems that measure our minutes and grudgingly yield a day or two of paid leave in the immediate aftermath of a death, and then only for an immediate family member. These bureaucratic systems are not ready for the coming cycles of delayed mourning.

And a similar problem will take place in our educational systems, where still too many teachers demand documentation of recent passing of a close relative to permit excused absences or extensions on assigned work. Some professors even joke about the “dead grandmother” excuse, not reckoning with the fact that grandparents do die. We’re going to have to shift our burdens of proof and timeliness.

Bereavement and excused-absence policies aren’t as deep a need as the spiritual and psychological burdens of delayed mourning, but it’s in these pragmatic policy spaces where inequalities emerge. My boss has made it clear that I can take as much time away as I want, and there’s no question that when we have our memorial in August, or November, or a year from now, my boss will let me go to that too. But having a good boss is not a system.

Preachers and teachers, HR executives, parents, coaches, friends, we all need to think about how we can build more space in our work, families and communities to make space for a long process of grieving. It’s not just about policy. Everyone you meet – and you too, even if you aren’t quite ready to face the trauma yet (I don’t blame you!) is waiting to properly mourn all the things we’ve lost this last year. That we’re still losing. We’re going to need to engage each other without demanding that people prove they are still struggling. Assume that everyone is struggling with the trauma of living through a year of mass death, faced mostly alone.

As we crest into, hopefully, someday, a post-Covid world, the traumas of this past year will be slow to fade. I hope we can face them as communities, building pathways for mutual support, flexibility and healing.