Two years ago, Joanne Su was anxious about turning 30 years old.

She worked for a foreign trade company in China’s southern metropolis of Guangzhou, earned a decent income and spent her weekends hanging out with friends. But to Su and her parents, there was one problem – she was single.

“Back then, I felt like 30 years old was such an important threshold. When it loomed closer, I came under tremendous pressure to find the right person to marry – both from my parents and myself,” she said.

Now 31, Su is still single, but says she is no longer worried. “What’s the point of making do with someone you don’t like, and then divorcing in a couple of years? It’s only a waste of time,” she said.

Su is among a growing number of Chinese millennials who are postponing or eschewing marriage entirely. In just six years, the number of Chinese people getting married for the first time has fallen by a crushing 41%, from 23.8 million in 2013 to 13.9 million in 2019, according to data released by China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

The decline is partly due to decades of policies designed to limit China’s population growth, which mean there are fewer young people in China available to be married, according to Chinese officials and sociologists. But it’s also a result of changing attitudes to marriage, especially among young women, some of whom are growing disillusioned with the institution for its role in entrenching gender inequality, experts say.

In extreme cases, some even took to social media to insult wives as being a “married donkey,” a derogatory term used to describe submissive women who conform to patriarchal rules within marriage, said Xiao Meili, a leading voice in China’s feminist movement.

“This kind of personal attack is wrong, but it shows the strong fear towards marriage felt by many. They hope all women can realize that marriage is an unfair institution to both the individual, and to female as a whole, and thus turn away from it,” said Xiao, who once walked 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) to call for reform of China’s child sexual abuse laws.

The declining marriage rate is a problem for Beijing.

Getting young people to have children is central to its efforts to avert a looming population crisis that could severely distress its economic and social stability – and potentially pose a risk to Chinese Communist Party rule.

“Marriage and reproduction are closely related. The decline in the marriage rate will affect the birth rate, which in turn affects economic and social developments,” Yang Zongtao, an official with the Ministry of Civil Affairs, said at a news conference last year.

“This (issue) should be brought to the forefront,” he said, adding that the ministry will “improve relevant social policies and enhance propaganda efforts to guide the public to establish positive values on love, marriage and family.”

Alarming statistics

In 2019, China’s marriage rate plunged for the sixth year in a row to 6.6 per 1,000 people – a 33% drop from 2013 and the lowest level in 14 years, according to data from the Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Chinese officials have attributed the decline to a drop in the number of people of marriageable age, due to the one-child policy, a deliberate strategy introduced in 1979 to control China’s population.

But demographers have been warning for years of a looming population crisis. In 2014, the country’s working-age population started to shrink for the first time in more than three decades, alarming Chinese leaders.

The next year, the Chinese government announced an end to the one-child policy, allowing couples to have two children. It went into force on January 1, 2016, but both marriage and birth rates have dropped anyway. Between 2016 and 2019, birth declined from 13 per 1,000 people to 10 – a trend not helped by the fact women are emancipating and millennials have different values.

The decline of marriage is not unique to China. Across the globe, marriage rates have fallen over the past few decades, especially in richer Western countries. Compared with other East Asian societies like Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan, China still has the highest marriage rate, said Wei-Jun Jean Yeung, a sociologist at the National University of Singapore who has studied marriage and family across Asian societies.

But no other country has tried to social engineer its population in the way China did with its one-child policy.

That policy has also affected marriages in other ways, Yeung said. Chinese families’ traditional preference for sons has led to a skewed sex ratio at birth, especially in rural areas. Currently, China has a surplus of more than 30 million men, who will face a hard time looking for brides.

Social economic changes

Demographic changes alone don’t explain the drastic drop in China’s marriage rate. Women are becoming more educated, and economically more independent.

In the 1990s, the Chinese government accelerated the rollout of nine-year compulsory education, bringing girls in poverty-stricken areas into the classroom. In 1999, the government expanded higher education to boost university enrollments. By 2016, women started outnumbering men in higher education programs, accounting for 52.5% of college students and 50.6% of postgraduate students.

“With increased education, women gained economic independence, so marriage is no longer a necessity for women as it was in the past,” Yeung said. “Women now want to pursue self-development and a career for themselves before they get married.”

But gender norms and patriarchal traditions have not caught up with these changes. In China, many men and parents-in-law still expect women to carry out most of the childcare and housework after marriage, even if they have full-time jobs.

“The whole package of marriage is too hard. It’s not just marrying someone, it’s to marry the in-laws, take care of children – there are a lot of responsibilities that come with marriage,” Yeung said.

Meanwhile, job discrimination against women is commonplace, making it difficult for women to have both a career and children.

“More and more young women are thinking: Why am I doing this? What’s in there for me?” said Li Xuan, an assistant professor of psychology at New York University Shanghai who researches families. “(The gender inequality) is really making young Chinese female hesitate before getting into the institution of marriage.”

To make matter worse, the grueling long hours and high pressure at work have left young people little time and energy to build relationships and maintain a family life, Li said.

Statistics show both genders are delaying marriage. From 1990 to 2016, the average age for first marriages rose from 22 to 25 for Chinese women, and from 24 to 27 for Chinese men, according to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

The figures in big cities are even higher. For example, in Shanghai in 2015, the average age for first marriages was 30 for men and 28 for women.

Su, the 31-year-old from Guangzhou, has often heard from married friends about the burden that comes with married life.

“Nowadays, women’s economic capability has improved, so it’s actually quite nice to live alone. If you find a man to marry and form a family, there will be much more stress and your life quality will decrease accordingly,” she said.

The increased social and economic status of women has also made it more difficult to find a suitable partner for two groups at the opposite ends of the marriage market: highly educated, high-earning women and low-educated, low-income men.

“Traditionally, Chinese women want to ‘marry up’ – that means marrying someone with higher education and income than themselves – and men want to ‘marry down,’” Yeung said. That preference has largely remained in place, despite the rising education and income levels status of women.

Shifting values

There has also been a shift in values towards love and marriage – changes that have come a long way since the founding of modern China.

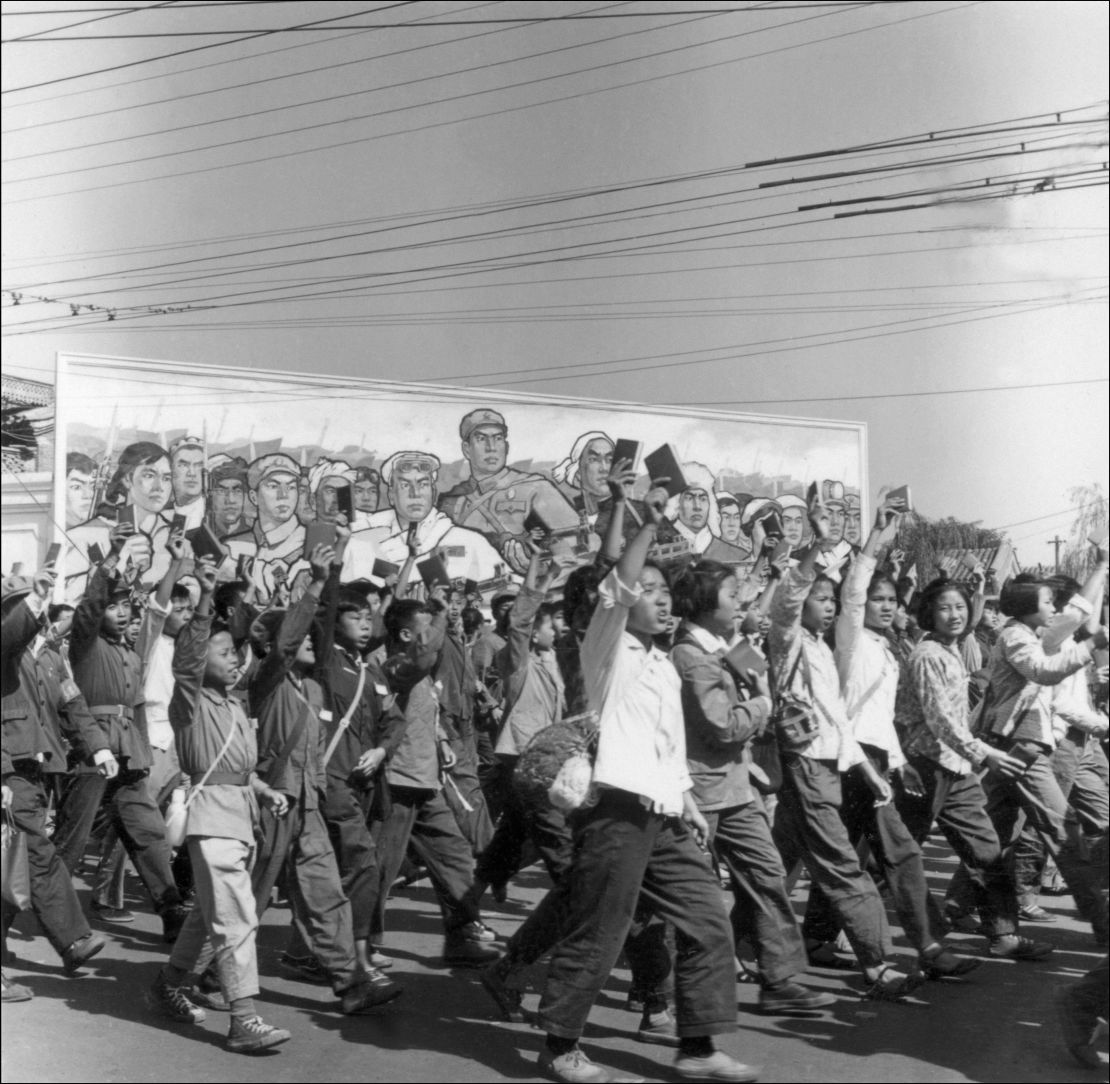

“During Mao’s era, marriage wasn’t a personal choice,” said Pan Wang, an expert on marriage in China at the University of New South Wales. During the Great Leap Forward, the ruling Communist Party encouraged people to have as many children as possible, as the country needed labor to build a socialist economy. Marriage, therefore, played a key role in socialism and nation building, she said.

In 1950, China passed the New Marriage Law, which outlawed arranged marriages and concubines, and enabled women to divorce their husbands. But in practice, arranged marriages remained commonplace, and the language of freedom of marriage and divorce was not translated into the freedom of love, Pan said.

“During the Cultural Revolution period, when you talked about love, that was (seen as) something capitalist, something people needed to struggle against,” she said.

Much has changed since then. Having grown up with more freedoms than their parents and grandparents after China’s reform and opening up, some Chinese millennials no longer see the institution of marriage as an obligation, but a personal choice.

Increasing social acceptance of cohabitation and premarital sex, as well as the wide availability of contraception and abortion, has enabled young people to enjoy romantic relationships outside the legal institution of marriage. They see marriage as an expression of their emotional connection, not just a means of reproduction.

Star Tong, 32, used to believe that romance, marriage and childbirth are things that should happen once a girl hits her mid-20s. Worried about being single, she attended about 10 blind dates – mostly set up by her parents – after she turned 25.

But none of them worked out – Tong insists on finding a partner who shares her values and interests, and refuses to settle for someone just for the sake of tying the knot.

“Now I’ve realized getting married is not the only option,” she said,”And it’s totally fine to just be by myself – I’m perfectly happy, have plenty of friends, and can focus my attention on advancing my career and taking care of myself and my parents.”

Tong said she felt encouraged by what she saw as a shift in society’s attitudes towards single women.

In 2007, the state-backed All-China Women’s Federation used “leftover women” to describe unmarried women over 27 years old. Later in the year, the Ministry of Education even added the term to the official lexicon, further popularizing its use.

Since then, the term has frequently made headlines and dominated online discussions, often as a criticism of highly educated women deemed “too picky” in the search of a partner. In recent years, the term has drawn criticism from feminists and scholars, and in 2017, the flagship newspaper of the Women’s Federation said it would no longer use the discriminatory term in its coverage.

During festive family gatherings, Tong was often lectured by relatives not to be “too picky” when looking for a partner. “I used to think ‘picky’ is a derogatory term,” she said. “But now, I think it’s about me choosing what I want. And there’s nothing wrong in that.”

Rising costs

Then there is the problem of the cost.

For many Chinese families, buying a home is a prerequisite for marriage. But many young couples simply don’t have the money to pay for an expensive property – and not every parent has enough savings to help out.

Li Xuan, the psychologist at NYU Shanghai, said even if buying an apartment is not necessarily wanted by everyone, the social and welfare system in China is built in such a way that home ownership has become almost crucial for couples looking for a better future for their children.

For example, owning a home near a good school grants access to high-quality education for their children, and wealthy couples are often willing to pay a high price for these coveted properties.

Joanna Wang, a 24-year-old student from the southwestern city of Chengdu, has been with her boyfriend for three years. The university sweethearts plan to live together in Shanghai when she graduates from her Master’s program in Hong Kong, but have no immediate plans to marry.

“Everything about getting married costs money, but I can’t make money faster than these expenses,” she said.

And the financial pressure is not only being felt in cities. In rural areas, the families of grooms must pay a “bride price” to her family – usually in the form of a large sum of cash, or a house. The practice has existed in China for centuries, but the costs have soared in recent decades due to the worsening gender imbalance – namely a surplus of rural bachelors, due to the one-child policy and rapid urbanization, which has encouraged many women to move to cities for work.

The Chinese government is worried

With a looming population crisis on the horizon, the Chinese government has introduced a flurry of policies and propaganda campaigns exhorting couples to have children. State media lectured couples that the birth of a child is “not only a family matter, but also a state affair.” In cities and villages, propaganda slogans advocating for a second child went up, replacing old ones threatening strict punishment in violation of the one-child policy.

“The government wants to keep new kids coming,” said Li, the psychologist from NYU Shanghai.

Following the two-child policy, provincial governments extended maternity leave beyond the 98 days mandated by national standards, with the highest reaching 190 days. Some cities also started giving cash subsidies to couples with a second child.

In 2019, several delegates to the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislature, proposed lowering the minimum marriage age to 18 for both sexes from 22 for men and 20 for women, to encourage young couples to marry earlier and have more babies. But the proposal drew criticism and ridicule online, with many pointing out that it is the social and financial pressure, instead of legal age limits, that has led young people to put off marriage.

Meanwhile, the Communist Youth League – the CCP’s youth branch – has picked up the task of matchmaking, holding mass blind dating events to help singletons find life partners.

Authorities are not only encouraging young people to get married, they are also trying to keep married couples together.

Last year, China’s national legislature introduced a 30-day “cooling-off” period for people filing for divorce, which went into force this year. The new law provoked criticism online, especially from women, who fear it will make it harder to leave a broken marriage – especially for victims of domestic violence.

But so far, none of these policies appear to have reversed the fall in marriage rates.

A big part of the problem, according to experts, is none of the policies address the entrenched gender inequality that has deterred young women from entering the institution of marriage and family life – such as traditional gender roles and job market discrimination against women.

Li said she has observed a revival of more traditional gender roles in government propaganda in recent years. “It has a lot to do with governmental plans, and how the government sees young men and women as social resources,” she said.

“Nowadays, there’s a very strong need for care work given the culture of intensive parenting and the growing number of elderly. With the retreat of state welfare, we need more and more people to shoulder childcare and elderly care, and women are the ‘default’ pool of labor for such work. So I think that is part of the reason for them to be pushing women back into the family life.”

Discrimination against women at work has also worsened since the relaxation of the one-child policy, as employers worry that women will now have a second child and take more maternity leave, said Xiao, the activist.

With these problems unresolved, the pressure from the state for young women to get married, stay married and have children will only further estrange them from it, she said.

“(The government) needs to change its way of thinking and encourage women to give birth from the aspects of protecting women’s rights. They shouldn’t treat women’s uterus as a water tap, one that they can turn off and on as they wish,” Xiao added.