The United States’ determination that China is committing genocide in Xinjiang presents a rare moral predicament for athletes and countries preparing to compete in the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

Outgoing US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made the announcement on the last day of the Trump administration, drawing attention to the systematic abuse of the minority Uyghur population in China’s far west.

The designation is the first by the US State Department since 2016, when then Secretary of State John Kerry determined that the atrocities committed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria amounted to genocide, and only among a handful of times a US administration has applied the term to an ongoing crisis.

Genocide is defined by the United Nations as “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group,” and although the US determination won’t trigger any immediate penalties, it will put pressure on anyone who does business with China – and that includes the 90 or so nations that are due to send athletes to the Winter Games in February next year.

“Right now there is a lot of pressure on any kind of major engagements with the Chinese government that involves lending (them) legitimacy,” said Maya Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch.

The prospect of US athletes competing in the capital of a country accused of carrying out an ongoing genocide, will at the very least send mixed messages about Washington’s commitment to human rights.

Beijing has long denied claims of genocide, claiming its policies in Xinjiang are part of a program of mass deradicalization and poverty alleviation. Last week a spokeswoman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry accused Pompeo of spreading “venomous” lies, inviting people to visit Xinjiang to “see with your own eyes.”

Politicians in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada and the US have publicly raised the prospect of not sending athletes to Beijing in 2022. While in March last year, 12 US senators led by Republican Rick Scott submitted a bipartisan resolution requesting that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) remove the 2022 Games from China and reopen the bidding process. But to date no government or national sports authority has officially announced it will be pulling out.

CNN has reached out to the US Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) for comment.

In a statement to CNN, the IOC said that it had received “assurances” from Chinese authorities that the principles of the Olympic Charter will be respected at the Beijing 2022 Games.

“Awarding the Olympic Games to a National Olympic Committee (NOC) does not mean that the IOC agrees with the political structure, social circumstances or human rights standards in its country,” the statement said.

Activists and experts said that US’ accusations will undoubtedly fuel calls for at least a partial boycott of the Games. In September 2020, more than 160 human rights groups around the world wrote to the IOC to reverse its decision to hold the 2022 Games in Beijing.

Mandie McKeown, executive director of the International Tibet Network, who coordinated the letter, said that if they were to put together another group letter now, the number of organizations would “undoubtedly” be higher.

She said if the Games couldn’t be canceled, then her organization was advocating for a diplomatic boycott of the event, which would allow teams to attend while world leaders stayed away.

“The push for diplomatic boycott is definitely growing and noises (from governments) are positive,” McKeown said.

Politicizing the Games

Over the years there have been many calls for Olympic boycotts, either over alleged human rights abuses or for political purposes.

In 1936, shortly before the beginning of World War II, pressure was placed on countries to boycott the Summer Olympics in Berlin, which was presided over by then-Chancellor Adolf Hitler.

In 1976, more than 20 African nations boycotted the Montreal Summer Games over the participation of New Zealand athletes, after the country’s rugby team defied the United Nations to go on a controversial tour of apartheid South Africa.

During the Cold War, the US and its allies boycotted the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow after which the Soviet Union then boycotted the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

But Susan Brownell, an Olympics expert and professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri-St Louis, said that from the Winter Olympics in Albertville in 1992 onwards there had been no national boycotts.

“A broad consensus opposing boycotts emerged among national governments worldwide because of the feeling that they accomplish nothing and only harm the athletes,” she said.

There was a push by human rights organizations and NGOs for a boycott of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics over the Chinese government’s restrictions on civil liberties, especially in regards to Tibetan minority groups, but in the end the Olympics went ahead as planned. “No-one with the power to withdraw from the Games was seriously considering it,” Brownell said.

But since then, allegations against Beijing in relation to mass detention camps in Xinjiang have mounted. Beijing claims it’s offering Muslim minorities, including the Uyghurs, an education in Chinese language and values as part of its anti-terrorism program.

“Languages, traditional cultures and customs of all ethnic minorities in Xinjiang have been well protected and inherited. All residents fully enjoy their rights, including the right to subsistence and development,” said Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying on January 20.

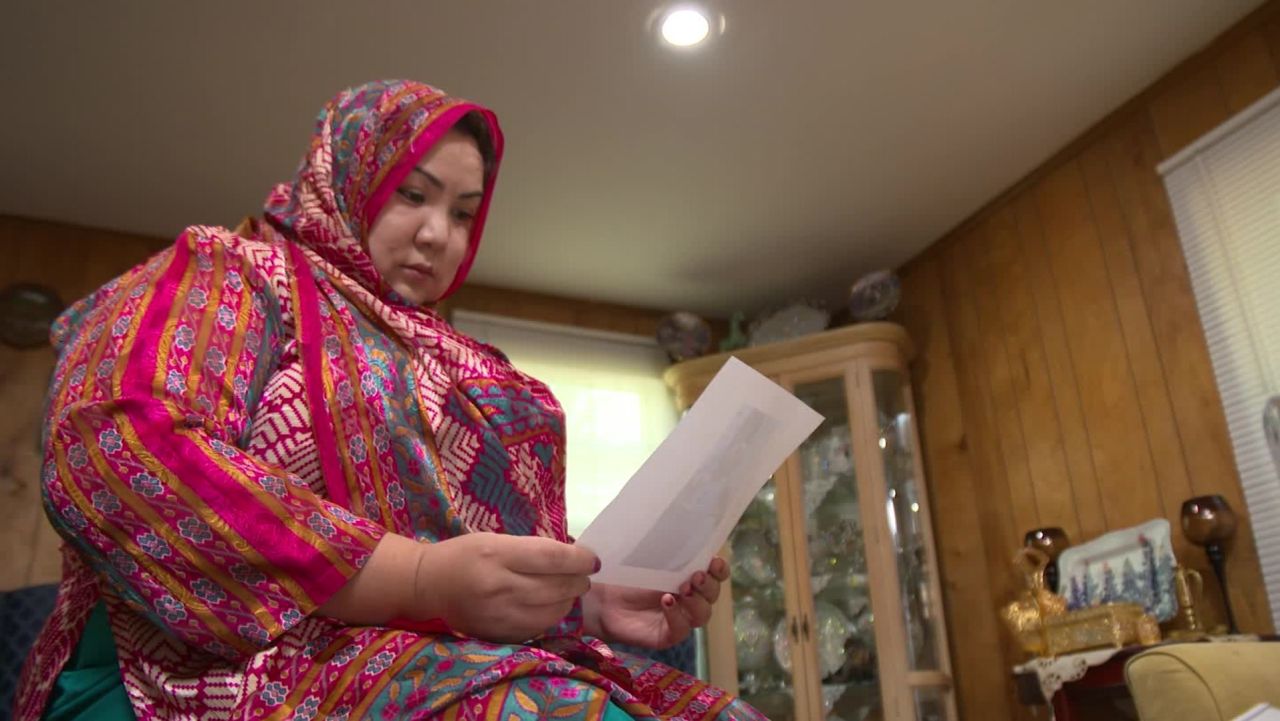

However, Uyghurs in exile say their families are being imprisoned for arbitrary offenses and subjected to forced labor and abuse.

Even without formal boycotts, the 2022 event is likely to attract protests, though mass demonstrations won’t be possible in a country that prides itself on maintaining order.

McKeown, from the International Tibet Network, said her organization and other groups working with it would be undertaking a program of action, including protests around the world, in the lead up to the 2022 Beijing Games to draw attention to the Chinese government’s human rights abuses.

She said for now they were advocating for a political boycott, rather than a total boycott, for the sake of the athletes.

“Athletes have worked incredibly hard to get where they are. It’s not necessarily their concern that the IOC made such a terrible mistake in giving the Games to Beijing,” she said.

Individual athletes could still boycott the 2022 Games, although this would mean compromising years of training and lucrative sponsorships. Under Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, any political protests by individual competitors at the Games are banned.

‘The power of sport’

An Olympics can still be heavily political even if there’s no boycotts, and the 2022 Beijing Games are likely to be no exception.

In 2018, at the Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, North and South Korea marched in the Opening Ceremony under a United Korea banner, a powerful symbol of unity between the two divided nations.

But the 2018 Games came at the same time as rising tensions between the US and North Korea. At the Opening Ceremony, then-US Vice President Mike Pence appeared to act coldly towards North Korean representatives, including the sister of leader Kim Jong Un.

A boycott by Western political leaders of the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2022 Games is possible, said Olympic expert Brownell, but she added that given Winter Olympics rarely attracted the attention of the Summer Games, many leaders were unlikely to go in the first place.

Brownell said that she believed the worst damage to the Olympics’ reputation didn’t come from an association with China or human rights issues. “The damage seems to have come from the perception of excess cost to the taxpayer and corruption in the IOC,” she said.

Despite the genocide ruling by the US, no countries have publicly moved to downsize relations with the Chinese government. And signs point to stronger ties, not weaker. In late December, for example, the European Union struck a wide-reaching investment agreement with Beijing despite the concerns of human rights organizations.

Human rights activists said it was too early to say whether or not a boycott of the 2022 Games, political or otherwise, was likely to go ahead.

And that’s assuming the Games even go ahead as planned. Events in Beijing are scheduled to begin on Friday, February 4, 2022 – just over 12 months away. But as the postponement of last year’s Summer Games in Tokyo has shown, the coronavirus pandemic has thrown doubt on countries’ ability to host large sporting events.

With numerous potential problems ahead, Wang, of Human Rights Watch, said the Chinese government needed to be given a chance to respond to international concerns over their actions in Xinjiang and the crackdown on civil liberties in Hong Kong.

But Wang said that she found it hard to see that happening and without demonstrable changes in Beijing’s behavior, there could be a “change of perception among other governments.”

“They are going to have to make a decision,” Wang said. Human Rights Watch is currently not calling for any boycott of the 2022 Games.

In response to a question about a potential boycott in 2022 on January 20, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said that “preparations are being smoothly carried out.” “We have confidence that it will be an extraordinary gathering,” she said.

In 2017, the IOC announced that it would add human rights, anti-corruption and sustainable development clauses to Olympic Host City contracts in the future. However, the new rules will only come into place after the 2022 Winter Olympics, beginning with the 2024 Summer Games. It is unclear how the clauses will be policed or what will happen if a host city breaks them.

In its statement to CNN, the IOC said that it recognizes and upholds human rights but at the same time, couldn’t change laws or the political system in a sovereign country. “This must rightfully remain the legitimate role of governments and respective intergovernmental organizations,” the statement said.

The IOC said that the Olympic Games had a unique role in bringing the world together.

“In our fragile world, the power of sport to bring the whole world together, despite all the existing differences, gives us all hope for a better future,” the statement said.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly named Munich as the host city of the 1936 Olympic Games. The Games were held in Berlin.