Editor’s Note: Lisa Gitelman is a professor in the departments of English and Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University. Her most recent book is “Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents.” The views expressed in here are the author’s own. Read more opinion on CNN.

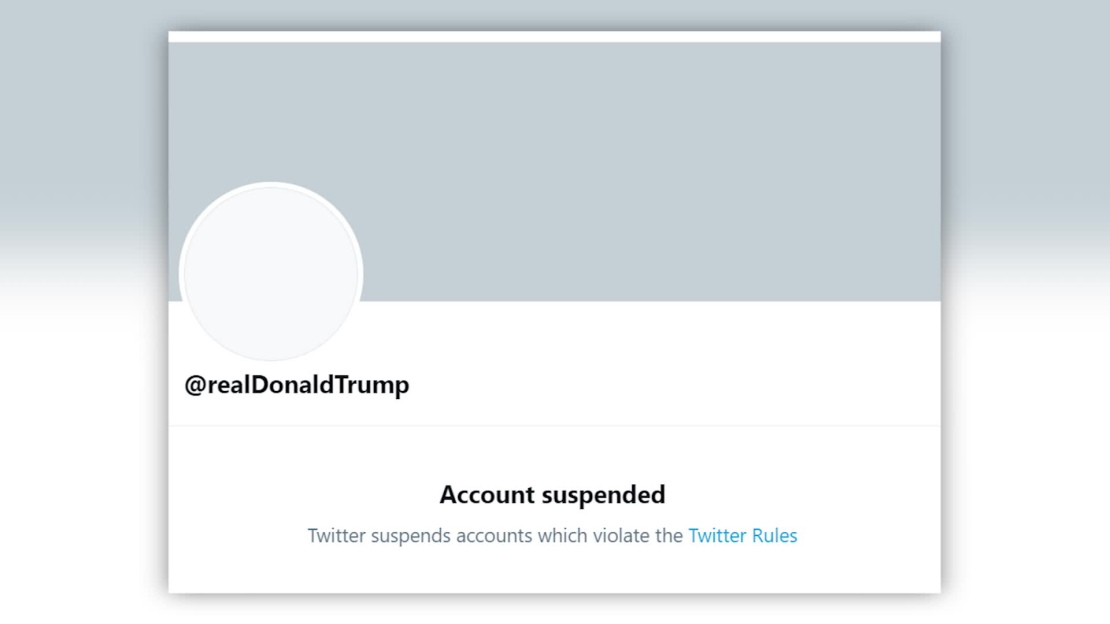

The President who tweets is now gone from Twitter. Whether they followed @realDonaldTrump or not, Americans are now facing a jarring readjustment – on top of what is otherwise already a moment of national crisis (or several). To know that daily life is now no longer subject to the sudden insults, dire policy pronouncements or signal-boosting of conspiracy theories that made up the soon to be former President’s feed is, for many, a comfort. But the suspension of @realDonaldTrump doesn’t erase the meaning or power exerted by the last four years of his tweets.

Recent cries of “censorship” from right-wing figures invoking British author George Orwell make this plain. Even as the de-platformed, who include more than Trump himself, and the pundit class focus on possible destinations for continuing their far-right conversation online, missing tweets by President Donald J. Trump still matter for a different reason. We may no longer see them, but they are, in very real ways, still with us.

At stake is how his social media posts will survive as part of the historical record as well as how we should remember @realDonaldTrump. Historians and others are already raising important questions about what aspects of America’s recent history are at risk of being lost if the President’s tweets are not properly preserved in their full context. No other commander in chief has executed as much of his presidency on Twitter as Trump has. To lose access to that material would be to lose sight of what made Trump Trump for much of the time he was in office.

There is, of course, a more immediate reason his tweets should be available for both lawmakers and the public to see. The historic second impeachment of a sitting president hinges on accusations of incitement in relation to the insurrection at the US Capitol. While Exhibit A in any trial before the Senate could certainly be Trump’s speech at the protest rally on January 6, attended by many who later turned toward the Capitol and became a violent mob, it is not too difficult to imagine that Exhibits B, C and D are likely to be Trump tweets. When the Senate tries Trump, as when history eventually judges him, the contexts for his words – not just the words themselves – will be critical to understand.

And mustn’t the contexts of tweets, in both cases, somehow include Twitter? Taking words off platform robs them of their original context. Unless we can see the ways Trump’s tweets appeared in his feed and a follower’s timeline, it will be difficult to judge their full meanings.

The Library of Congress once tried to archive Twitter – all of it – but a usable collection of tweets never materialized. We can expect that the National Archive will do a better job with Trump’s tweets, since it’s been working with Twitter to capture them and make them accessible when the rest of his records are made publicly available. However, all presidential records are embargoed for five years.

At least one private collection of Trump’s tweets (including deleted ones) exists now, publicly available at thetrumparchive.com, courtesy of a programmer named Brendan. And as the National Archive prepares to receive Trump’s official papers starting on January 20, officials have assured the public that all of his tweets will be included.

But any Twitter user knows that something is lost when tweets are separated from Twitter: the social part of social media. How might we recover or document the ways that tweets originally appeared online, not just how many “likes” and retweets they garnered, but by whom? How were they interlinked with other content and replied to, trending and streamed in the moment by Twitter’s algorithms? “Covfefe” made sense somehow on Twitter in 2017 (to the extent that everyone knew what you were referring to if you said it). How exactly did “LIBERATE MICHIGAN” make sense in 2020 and to whom? Those are questions historians and others looking back decades from now may well be asking. Considering how often the word “unprecedented” has been used to describe this administration, it’s clear those answers and many more will matter to future generations (and to our own).

This isn’t the first time that innovations in communication have prompted questions about the historical record. When President Ronald Reagan left office in January 1989 email presented a new problem, so much so that an epic tangle of litigation ensued. Archivists and historians wanted to be sure that emails were preserved, and they agreed that printouts (which might lack relevant information about transmission) were not satisfactory. This dispute helped to raise public awareness about electronic records, and it helped to create consensus among professional archivists about relevant best practices.

We face another such moment today, now that electronic records include those that are native to our smartphones and social media platforms. What’s more, lawmakers and the public remain rightly concerned that all sorts of other materials relating to the outgoing administration may be at peril. At least one lawsuit is already underway in the hopes of preventing the outgoing administration from destroying records created using unofficial channels like WhatsApp.

The de-platforming of Trump and QAnon-related accounts has called renewed attention to the role that private corporations have been allowed to play in regulating political speech. Americans also need to be attentive to the role those corporations have assumed in creating and collecting, if not preserving, the historical record.

So far, self-appointed individuals and private non-profits have been leading some notable preservation efforts. All of Parler, we learn, has been scraped – that is saved – by a hacker calling herself @donk_enby, who sprang into action when Amazon Web Services announced last week that it would stop hosting the conservative platform. And over at the Internet Archive (archive.org) users can browse an inspiring collection of obsolete webpages, but they should expect lots of dead links and zero dynamic content. Is that what we should expect from a historical collection of social media?

As Twitter without @realDonaldTrump turns its attentions elsewhere – Sports and K-pop are trending as I write this – it can’t hurt to be a little more self-conscious about social media as a kind of participatory history in the making. For one thing, that might make us more judicious users of social media.