Science’s biggest achievement in 2020 was undoubtedly the rapid development of effective vaccines against Covid-19 – a massive feat that should be widely celebrated and lauded with prizes in the years to come.

Away from the coronavirus pandemic, however, there were discoveries in many different fields that inspired much-needed moments of awe and wonder in this tumultuous year.

As 2020 comes to a close, here is a roundup of some of the fascinating findings you may have missed.

Ancient humans: Skulls, chewing gum and a prehistoric Picasso

We learned a lot more about our ancient relatives in 2020 – other species of humans that existed before and, in some cases, alongside early Homo sapiensin the centuries and millennia before we emerged as the lone hominin survivor.

The oldest skull belonging to Homo erectus, the earliest humans to have body proportions similar to Homo sapiens and known for migrating out of Africa, was found in pieces in the Drimolen archaeologicalsite just outside Johannesburg. It belonged to a young child, only about 2 or 3 years old, and was dated to between 1.95 and 2.04 million years ago. Until this discovery, the oldest erectus fossil came from Dmanisi, Georgia, and was dated to 1.8 million years ago.

A piece of late Stone Age chewing gum also yielded an extraordinary story.

Geneticists were able to sequence the genome and oral microbiome of the last person to chew the birch pitch – a girl who lived 5,700 years ago in what’s now Denmark. Scientists were able to deduce what she had for her last meal and that she couldn’t stomach dairy. It was the first time human genetic material had successfully been extracted from something besides human bones.

A tiny piece of cord from a French cave further undermined the idea that Neanderthals were cognitively inferior to Homo sapiens. The discovery of a 41,000 to 52,000-year-old yarn fragment wrapped around a thin stone tool showed that Neanderthals had an understanding of basic math concepts needed to make the yarn and suggested that it was possible Neanderthals could manufacture bags, mats, nets, fabric, baskets, snares and even watercraft.

“It opens a new window on the cognition of Neanderthals and their ability to organize their way of life,” said Marie-Hélène Moncel, who is a director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

Finally, take a minute to marvel at the oldest rock art created by humans.

It was found in Indonesia and depicts a hunting scene that experts say changes our view of early human cognition. Science labeled its discovery a runner-up for its breakthrough of the year, saying it decisively unseats Europe as the first place where modern humans are known to have created figurative art.

“If the figures do depict mythical human-animal hunters, their creators may have already passed an important cognitive milestone: the ability to imagine beings that do not exist,” the magazine said.

Dinosaurs, crazy beasts and other ancient life

Dinosaur bellies and evidence of their diets are rarely preserved in the fossil record. The last meal eaten by an armored nodosaur just before it died, however, was captured in exquisite detail, according to a study of a unique fossil published in June.

This discovery gave definitive evidence of what a large herbivorous dinosaur ate — in this case, a lot of chewed-up fern leaves, some stems and twigs. The details of the plants were so well preserved in the stomach that they could be compared to samples taken from modern plants today.

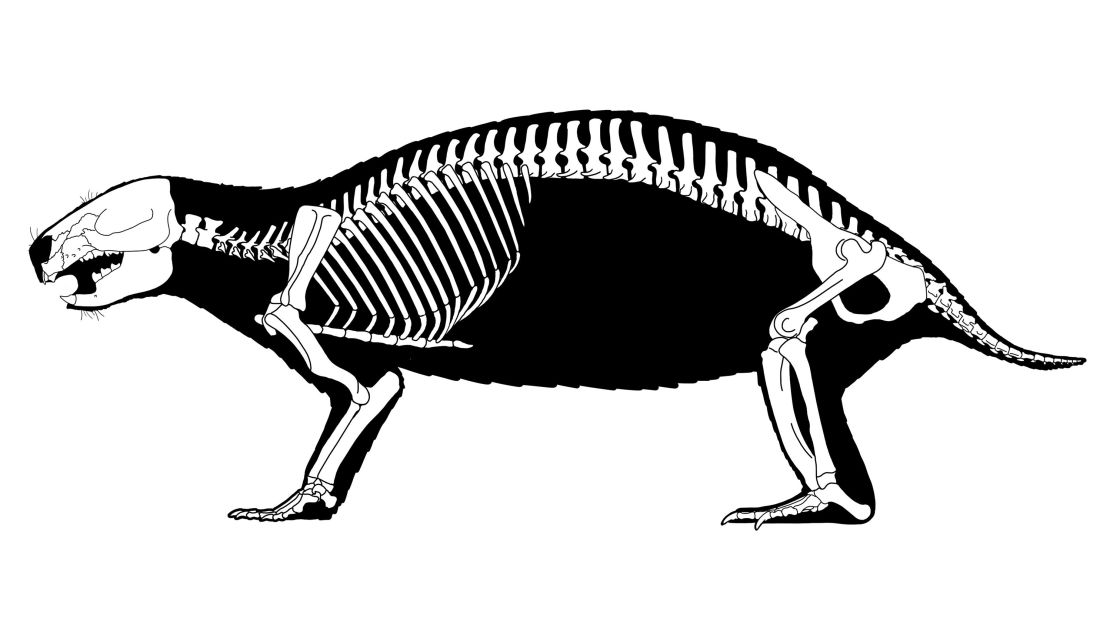

Around the time dinosaurs went extinct, an unusual mammal lived in the Southern Hemisphere. Its extremely bizarre features have perplexed paleontologists. Dubbed “crazy beast,” the discovery of Adalatherium was announced in the journal Nature inApril. The oddball animal, the size of an opossum, has more vertebrae than most other mammals, muscular hind limbs that were in a sprawling position similar to modern crocodiles, coupled with brawny sprinting front legs that were tucked underneath the body. Its front teeth were like a rabbit and back teeth completely unlike those of any other known mammal, living or extinct.

“Knowing what we know about the skeletal anatomy of all living and extinct mammals, it is difficult to imagine that a mammal like Adalatherium could have evolved; it bends and even breaks a lot of rules,” said David Krause, senior curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science in a December statement to mark the publication of a 234-page monograph on the animal by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology – a yearly publication on the most significant vertebrate fossils.

Going back far beyond dinosaur times to the origins of life, scientists discovered evidence of the oldest ancestor on the family tree that includes humans and most animals – a wormlike creature about the size of a grain of rice that was uncovered in South Australia.

The creature lived 555 million years ago and were an evolutionary step forward for early life on Earth.

Natural world: Ancient stardust and a towering coral reef

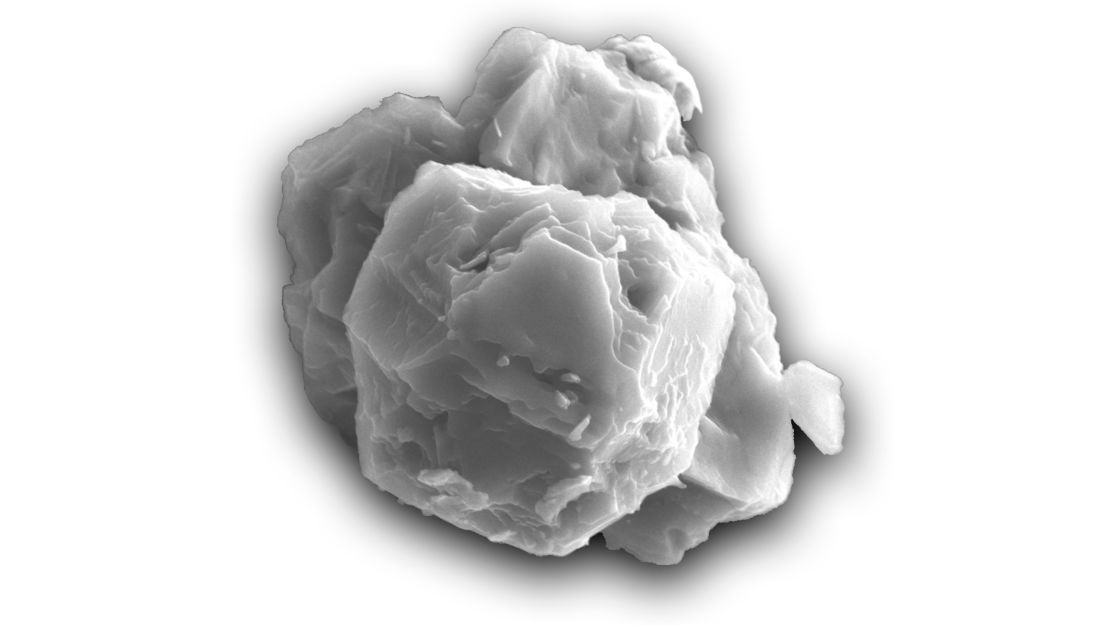

Fifty years ago, a meteorite fell to Earth and landed in Australia, carrying with it a rare sample from interstellar space. An analysis of the meteorite published in January revealed stardust that formed between 5 to 7 billion years ago. That made the meteorite and its stardust the oldest solid material ever discovered on Earth. Our sun is around 4.6 billion years old, meaning this stardust existed long before our sun or solar system were a reality.

Australian scientists made another stunning find in October. While mapping the seafloor off the coast of North Queensland, a team from Schmidt Ocean Institute came across a new vertical coral reef in the waters measuring 500 meters (about 1,600 feet) – making it taller than some of the world’s highest skyscrapers. It’s the first “detached reef” to be detected in the ocean depths in over 120 years.

Significant discoveries have been made in Siberia in recent years as warmer temperatures have caused the permafrost to melt, revealing mammoths, woolly rhinos and other creatures. In 2020, the tundra gave up more of its secrets.

Reindeer hunters discovered the perfectly preserved body of an Ice Age cave bear – the first example of the species ever to be found with soft tissues intact, it was announced in September. It could be up to 39,500 years old.

“Today this is the first and only find of its kind – a whole bear carcass with soft tissues. It is completely preserved, with all internal organs in place including even its nose,” said scientist Lena Grigorieva at North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, Siberia. “Previously, only skulls and bones were found. This find is of great importance for the whole world.”

History: Voices from the dead, Vikings’ surprising genetic diversity and brain cells turned into glass

In 2020, scientists found a way for us to hear the voice of an Egyptian priest who died over 3,000 years ago. Researchers in the United Kingdom re-created the sound by 3D printing a voice box after scanning the priest’s mummified remains. The team were able to accurately reproduce a single sound, which sounds a bit like a long, exasperated “meh” without the “m.” Take a listen:

Like the Egyptians, the Vikings have long been a source of fascination for moviemakers, and in popular culture they’re often depicted as blond-haired, Scandinavian warriors who pillaged their way through Europe. Research published in September, however, suggested we’d been getting that – and a lot more – wrong.

The biggest study of its kind used DNA technology to analyze over 400 Viking skeletons, and researchers found that many Vikings actually had brown hair. And they weren’t just from Scandinavia – they also had genes from both Asia and Southern Europe in their bloodline.

“The results change the perception of who a Viking actually was. The history books will need to be updated,” said Eske Willerslev, a fellow of St John’s College at the University of Cambridge in the UK. “We didn’t know genetically what they actually looked like until now.”

The cities buried when Mount Vesuvius in Italy erupted on August 24 in the year 79 A.D. are some of the world’s best studied archaeological sites, but scientists are still learning tantalizing new details.

In January, researchers published an analysis of a Vesuvius victim’s skull that belonged to a person found lying down on a bed buried by volcanic ash. Although the remains were found in the 1960s, the new analysis found that parts of the brain had been vitrified, or turned into a glassy black substance by the heat. Further investigation revealed cells in the vitrified brain and intact nerve cells in the spinal cord, which, like the brain, had been vitrified.

“This opens up the room for studies of these ancient people that have never been possible,” said Guido Giordano, a volcanologist at Roma Tre University who worked on the study.

Ashley Strickland, Amy Woodyatt, Harry Clarke-Ezzidio, Anna Chernova, Lianne Kolirin, Rory Sullivan and Sharon Braithwaite contributed to this report.