Judge Amy Coney Barrett, once confirmed, will be one of three current Supreme Court justices who assisted the legal team of then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush in the Florida ballot-recount battle that came down to a single vote at the Supreme Court.

The court’s December 12, 2000, decision cutting off Florida recounts tore apart the justices and the nation, and the case hovers in the air today as America approaches the November 3 presidential election.

Other current justices benefited from the decision giving Bush the White House over Vice President Al Gore, as they eventually became Bush appointees to the bench. Conversely, a pending judgeship for one of the current members was derailed by Bush v. Gore – temporarily.

Of the original nine who decided the case two decades ago, only two remain, Justices Clarence Thomas and Stephen Breyer. And they were on opposite sides.

Following are descriptions of the justices’ associations – some predictable, some serendipitous – with the milestone that would haunt any litigation reaching the justices in the race between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden.

Three who assisted Bush

Chief Justice John Roberts

Roberts flew to Florida in November 2000 to assist Bush’s legal team. He helped prepare the lawyer who presented Bush’s case to the Florida state Supreme Court and offered advice throughout.

Roberts also faced a singular personal challenge during the 36-day ordeal that extended from the November 7 Election Day to the court’s late-hour December 12 ruling. Then in private practice, Roberts was preparing to argue before the justices in a separate business case on November 29, and within days in December, the baby boy he and his wife had planned to adopt was born.

After Bush became president, he nominated Roberts to the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit (the Senate confirmed him in 2003); Bush then elevated Roberts to the chief justice position in 2005, to succeed William Rehnquist. During his Senate confirmation hearing, Roberts declined to reveal his view of the justices’ 2000 decision, saying a disputed election could come to the court again.

“Obviously, the particular parameters in that case won’t” return to the court, he said, “but it is a very recent precedent, and that type of decision is one where I thought it inappropriate to comment on whether I think they were correct or not.”

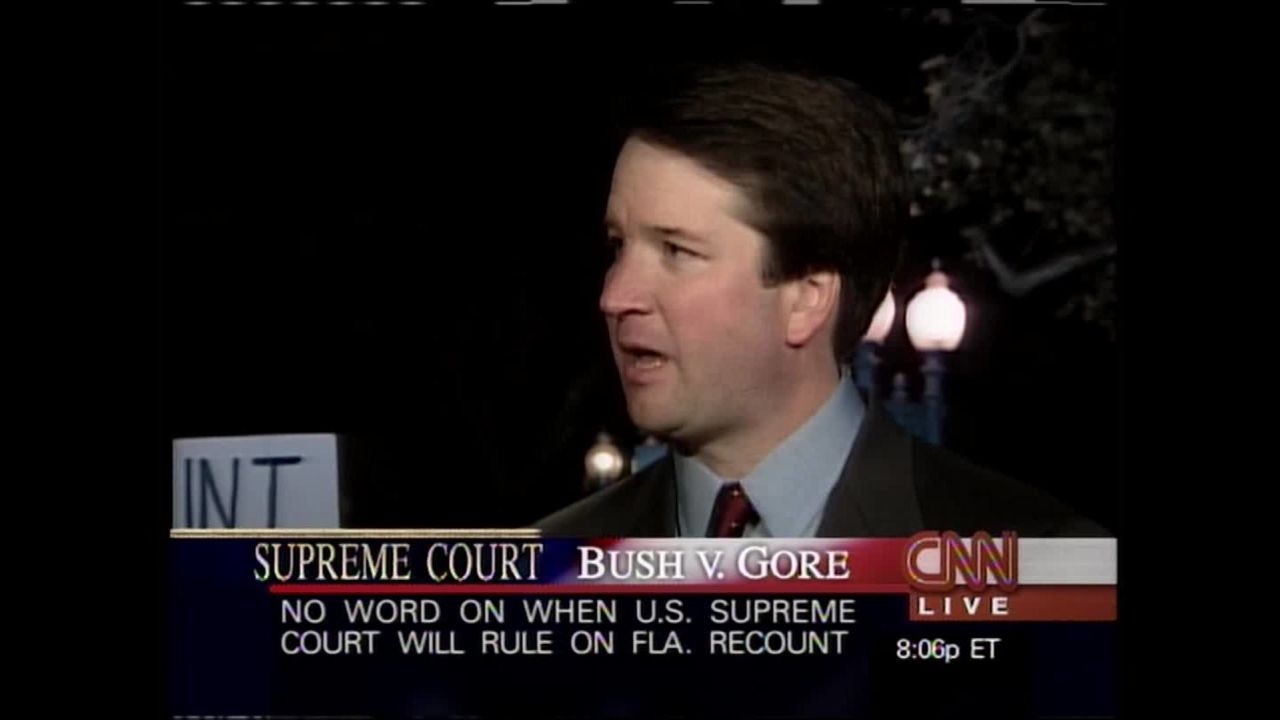

Justice Brett Kavanaugh

He was also in private practice in 2000 and helped the Bush legal team. He wrote on a 2018 Senate questionnaire that his work related to recounts in Volusia County, Florida.

In an interview with CNN in Washington after the justices had heard oral arguments but before they ruled, Kavanaugh said the justices were concerned about “the arbitrary, standardless nature of the recount process in Florida.” He dismissed a question about political differences, saying, “I don’t think the justices care if it’s Bush v. Gore, or if it were Gore v. Bush. What they care about is how to interpret the Constitution and what are the enduring values that are going to stand a generation from now.”

After the election, Bush hired Kavanaugh to be a counsel and then staff secretary. In the West Wing, Kavanaugh met his future wife, Ashley, who was Bush’s personal secretary. Bush appointed Kavanaugh to the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, where Roberts had first served. In 2018, Trump elevated Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.

During Kavanaugh’s Senate confirmation hearings, Democratic senators referred to his involvement in the Bush v. Gore litigation, but they did not ask him about the case.

Judge Amy Coney Barrett

Barrett wrote on the questionnaire she submitted to the Senate for her Supreme Court confirmation review, “One significant case on which I provided research and briefing assistance was Bush v. Gore.” She said the law firm where she was working at the time represented Bush and that she had gone down to Florida “for about a week at the outset of the litigation” when the dispute was in the Florida courts. She said she had not continued on the case after she returned to Washington.

During her hearings this week, she told senators she could not recall specifics of her involvement.

“I did work on Bush v. Gore,” she said on Wednesday. “I did work on behalf of the Republican side. To be totally honest, I can’t remember exactly what piece of the case it was. There were a number of challenges.”

Separately, under questioning from Democratic senators, Barrett declined to commit to recusing herself from any Trump election case. Trump has speculated that the Supreme Court could face another major lawsuit over the November presidential contest. “I think this will end up at the Supreme Court,” he said last month. “And I think it’s very important that we have nine justices.”

On the bench

Justice Clarence Thomas

He is the only remaining member of the five-justice majority that resolved Bush v. Gore. Thomas joined the unsigned opinion that said Florida had run out of time to recount disputed ballots without violating the constitutional guarantee of equal protection. The decision cemented the state’s late November certification of a 537-vote margin for Bush over Gore (from nearly 6 million ballots cast) and gave Bush Florida’s decisive electoral votes.

Thomas, a 1991 appointee of Bush’s father, President George H.W. Bush, also joined a concurring opinion with Rehnquist and Justice Antonin Scalia, finding additional constitutional flaws in a Florida state Supreme Court decision that had allowed the recounts to continue.

The day after Bush v. Gore was handed down, Thomas kept a previously scheduled meeting with high school students at the court. He told them the weeks preceding the decision had been “exhausting” but that he believed the process showed “the strength of our system of government.” He said politics had not been involved in the decision.

It was at this session that Thomas happened to reveal for the first time a “personal reason” for his habit of not asking questions at oral arguments. Born in rural Pin Point, Georgia, Thomas said he spoke with a Geechee dialect and was self-conscious as a child: “I just started developing the habit of listening,” he told the students.

Thomas is the only justice in the past 20 years who has cited Bush v. Gore as precedent in any subsequent case, with a footnote in a 2013 solo dissent. The court in 2000 had deemed its decision “limited to the present circumstances, for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities.”

Justice Stephen Breyer

He was one of the four dissenters and, with the September 18 death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, is the only one left on the bench. Each of the dissenting justices wrote separate opinions, although they signed on to parts of their colleagues’ views. In Breyer’s opinion, he declared that the majority seemed to abandon its “self-restraint” and traditional check on its exercise of power.

“(W)e do risk a self-inflicted wound – a wound that may harm not just the Court, but the Nation,” he wrote.

Breyer, a 1994 appointee of President Bill Clinton, for years afterward recalled his disappointment but referred to the upside of an ordered democracy. “Bush v. Gore’s mandate was followed without paratroopers being dispatched, without bullets being fired, without rocks being hurled, and even without punches being thrown,” he said in a 2009 appearance in Boston.

“To be sure,” he added, “people were angry with the decision and they continue to disagree with it. But they have also agreed to follow the decision because that is what occurs in countries that have judicial independence and are ruled according to law.”

The late Ginsburg criticized the majority in her separate opinion for abandoning its usual federalism and deference to state courts on state law. “Rarely has this Court rejected outright an interpretation of state law by a state high court,” she said. As she closed her opinion, she highlighted the stakes for the country: “In sum, the Court’s conclusion that a constitutionally adequate recount is impractical is a prophecy the Court’s own judgment will not allow to be tested. Such an untested prophecy should not decide the Presidency of the United States.”

Over the years, the 1993 Clinton appointee expressed her despair that December 12 evening and her delay in leaving the building, until Scalia telephoned and said, “Ruth, why are you still at the court? Go home and take a hot bath.” Ginsburg’s response: “Good advice I promptly followed.”

Other conservative justices

Justice Samuel Alito

He had been appointed in 1990 to the 3rd US Circuit Court of Appeals by President George H.W. Bush. At the time of Bush v. Gore, Alito was a decade into the job, writing opinions in his Newark, New Jersey, chambers and widely regarded as a possibility for the younger Bush’s “short list” of Supreme Court candidates.

The opportunity came in late 2005, when Bush tapped him to replace retiring Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. During Alito’s confirmation hearing in January 2006, senators asked his views about Bush v. Gore. “I hope … that sort of issue does not come before the Supreme Court again,” Alito said, observing that controversy swirled not only around what the justices had decided but also whether they should even have taken up the case.

Pressed on what he thought of the outcome, Alito begged off, saying, “I have not studied it in the way I would study the issue if it were to come before me as a judge and that would require putting out of my mind any personal thoughts that I had on the matter.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch

Like Kavanaugh, he worked in the George W. Bush administration and was appointed by Bush to a federal appeals court. But Gorsuch remained in private practice through the early 2000s. He joined the Bush administration in the second term, serving 2005-2006 in the Department of Justice. Bush selected the Colorado native in 2006 for the Denver-based 10th US Circuit Court of Appeals. Gorsuch was then elevated to the Supreme Court by Trump in 2017.

When then-Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican, asked Gorsuch about Bush v. Gore, he responded, “I know some people in this room have some opinions on that, I am sure, Senator. But as a judge, it is precedent of the US Supreme Court, and it deserves the same respect as other precedents of the US Supreme Court when you are coming to it as a judge.”

Obama’s nominees

Justice Elena Kagan

She was nominated to the federal appeals court for the DC Circuit by Clinton in 1999, after serving his administration in senior domestic-policy positions. Later that year, Kagan become a visiting professor at the Harvard Law School.

The Republican-controlled Senate never acted on her appeals court nomination, and the ruling in Bush v. Gore ensured that she would not be renominated by Clinton’s successor. Kagan continued to teach and in 2003 was appointed dean of the Harvard Law School.

When Democrat Barack Obama succeeded Bush in 2009, he named Kagan US solicitor general and then in 2010 appointed her to the Supreme Court. During her Senate confirmation hearing, Kagan declined to give her view of Bush v. Gore. “The question of when the court should get involved in … disputed elections is, I think, one of some magnitude that might well come before the court again.”

Added Kagan: “It’s hard to think of a more important question in a Democratic system.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor

In 2000, Sotomayor was a US appellate judge for the 2nd Circuit. Hearing cases in New York, she was removed from the election fallout in Florida and Washington. She had first been tapped to be a US district judge in 1992 by George H.W. Bush, then elevated to the appeals court by Clinton in 1998. When Obama came to office in 2009, he chose Sotomayor for his first appointment to the high court.

During her confirmation hearing, she said her reaction as a judge to Bush v. Gore “was not to criticize it or to challenge it.”

Of the Supreme Court’s down-to-the-wire involvement, she said, “It’s only happened once in the lifetime of our country” and added that since 2000, “enormous electoral process changes” have occurred.

Sotomayor concluded by telling senators: “That is a tribute to the greatness of our American system, which is whether you agree or disagree with a Supreme Court decision, that all of the branches become involved in the conversation of how to improve things.”