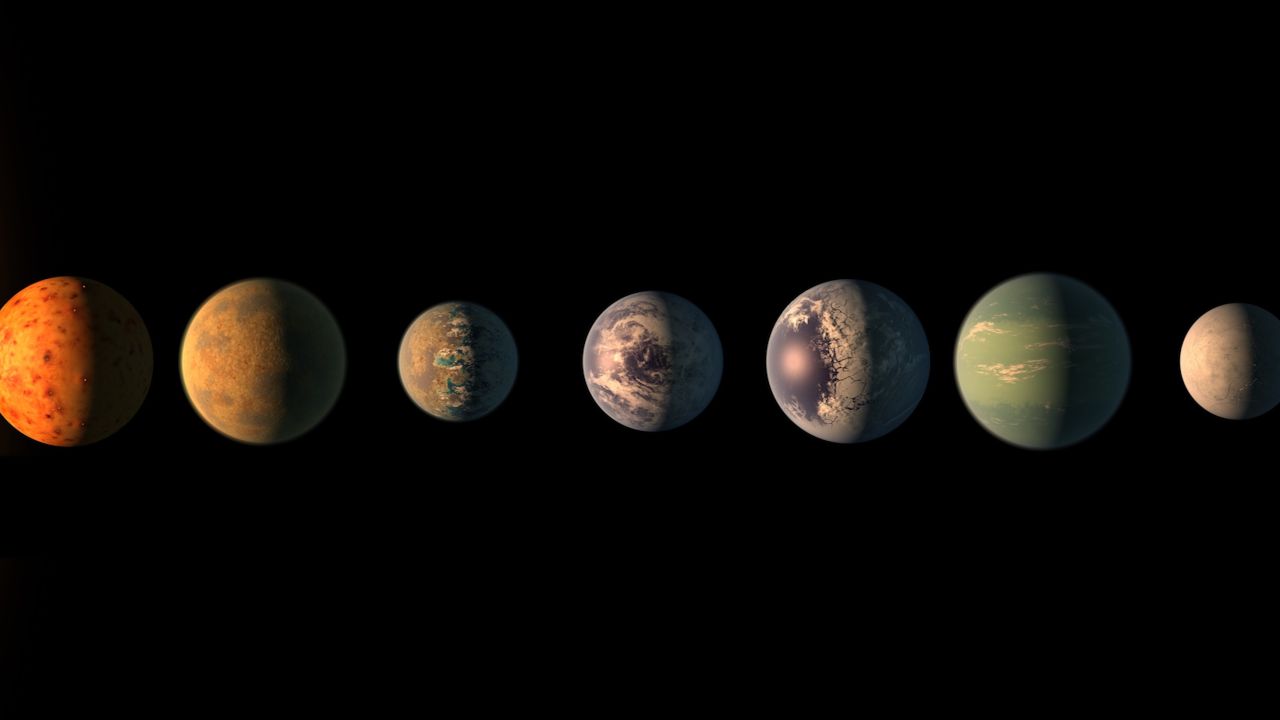

Earth is the only planet we know of so far to host life, but it may not be the best place for life when compared with “superhabitable” planets, according to a new study.

And as scientists search for other planets outside of our solar system, called exoplanets, that could host life, planets much like Earth may not be the best answer.

“We are so focused on finding a mirror image of Earth that we may overlook a planet that is even more well suited for life,” said Dirk Schulze-Makuch, lead study author and professor for astrobiology and planetary habitability at Washington State University, in an email to CNN. The study published in the journal Astrobiology on Monday.

In the new study, Schulze-Makuch and his coauthors identified 24 exoplanets and exoplanet candidates (planets that have not been positively confirmed as exoplanets). They are all more than 100 light-years away, that could be contenders for superhabitable planets with conditions more suitable for life than Earth.

However, the authors caution that this does not mean they have confirmed that life exists on these planets. Instead, it means that these planets could have conditions that are conducive to life.

“We caution that while we search for superhabitable planets, that doesn′t mean that they necessarily contain life (or even complex life),” Schulze-Makuch said. “A planet can be habitable or superhabitable but uninhabited. This has to do with the natural history of the planet. There could have been a calamity (like a nearby Supernova explosion).”

Schulze-Makuch identifies a superhabitable planet as “any planet that has more biomass and biodiversity than our current Earth.” Essentially, it would be slightly older, bigger, warmer and wetter than Earth, he said.

“The habitability of our planet has also changed throughout our natural history,” he said. “For example, Earth in the Carboniferous Time Period with all the swamps and rainforest (that produced most of our current gas and oil) was likely more habitable – superhabitable using our definition – than Earth currently.”

Stars with longer lifespans

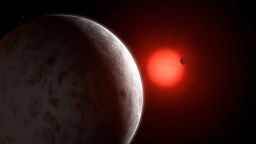

One factor of superhabitability may actually be the type of star the planets orbit. The researchers identify a K dwarf star as the most ideal in the study. These stars have a longer lifespan than our sun, so life could potentially persist and thrive on planets in orbit around them.

K dwarf stars are cooler, less massive and even less luminous than oursun, but they can persist for 20 billion to 70 billion years. Planets orbiting these stars would be older and allow time for life to reach the complexity we have on Earth.

Earth is about 4.5 billion years old. But in the study, the researchers suggest that five to eight billion years is actually the “sweet spot” for life to form and evolve.

Our sun has a lifespan of less than 10 billion years, and it took nearly four billion of those before any kind of complex life evolved on Earth. And stars similar to our sun could actually die before complex life could form on planets orbiting them.

Other criteria was used to determine superhabitability out of the 4,500 known exoplanets.

The planets were likely terrestrial, or rocky like Earth, and orbiting in the habitable zone of their star – meaning the distance from the star where liquid water could stably remain on the surface of the exoplanet.

They looked at size and mass and estimated that a planet about 1.5 times Earth’s mass would be able to maintain interior heating for longer than Earth and have a stronger gravity that would enable it to hold on to its atmosphere longer.

More water content on a warmer planet, about 8 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than Earth, may be more suitable to life, too. The study authors compared this preference for warmth and moisture to the biodiversity in Earth’s tropical rainforests – especially when compared with areas that are colder and more dry.

Of these criteria, Schulze-Makuch thinks the most important is for the planet to be hosted by a K dwarf star, and for the planet to be slightly older than Earth.

While a planet could be superhabitable and only meet some of the criteria without checking all of the boxes, the authors caution there is a lot more information that just can’t be evaluated about these planets.

Even “a slightly higher temperature could make things worse in times of habitability,” like extreme deserts on Earth, Schulze-Makuch warned.

Finding a superhabitable world

None of the 24 candidates meet all of the criteria laid out in the study because scientists simply don’t know enough about them to be able to tell. One of them, called KOI 5715.01, has four of the desirable aspects for a superhabitable planet.

It’s located in the Cygnus constellation about 3,000 light-years from Earth. The star is 77% the radius of our sun and 76% the mass of it, with only 34% of our sun’s luminosity. And the star is about 5.5 billion years old, or one billion years older than our sun.

The authors provide a bit of a report card for the star it orbits in the study based on what they know, which they admit isn’t much.

“The point is that these preliminary candidates for possibly being habitable or superhabitable should be selected and prioritized for further investigations,” Schulze-Makuch said. “Also, we have to better understand what makes a planet habitable and how biospheres interact with their natural environment.”

But to fully evaluate these candidates, Schulze-Makuch sees a need for probes or landing on the planet – but all of these are so far away, that isn’t likely. However, better remote observations with future space telescopes could help focus in more on the details of these planets.

“It’s sometimes difficult to convey this principle of superhabitable planets because we think we have the best planet,” Schulze-Makuch said. “We have a great number of complex and diverse lifeforms, and many that can survive in extreme environments. It is good to have adaptable life, but that doesn’t mean that we have the best of everything.”

Astronomer and planetary scientist Sara Seager sees this study as “a great resource for all to use as a reference.” Seager, also a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was not involved with the study.

“It’s a really nice description of all the ingredients for a habitable world,” Seager said in an email to CNN. “I love the concept of superhabitable exoplanets. The concept is a good one, like those Olympic athletes amongst us humans.”

And Seager agrees with what the authors say in the conclusion to their paper.

“Observations of habitable or super habitable exoplanets are still so exceedingly challenging that nature will ultimately dictate which targets we can followup with our next generation telescopes,” Seager said.

“That is follow up to see if the planet is actually habitable, if it has water vapor in its atmosphere (indicative of surface water on a rocky planet), potentially measure the planet’s and search for biosignature gases.

“So although the sample list of exoplanets is quite long, none are within 100 light-years andnone are suitable for follow up observations with our next generation telescopes.”