The brain cells of a young man who died almost 2,000 years ago in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius have been found intact by a team of researchers in Italy.

The discovery was made when the experts studied remains first uncovered in the 1960s in Herculaneum, a city buried by ash during the volcanic eruption in AD 79.

The victim, who was found lying face-down on a wooden bed in a building thought to have been devoted to the worship of the Emperor Augustus, was around 25 years old at the time of his death, according to the researchers.

Pier Paolo Petrone, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Naples Federico II who led the research, told CNN that the project started when he saw “some glassy material shining from within the skull” while he was working near the skeleton in 2018.

In a paper published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine, Petrone and his colleagues revealed that this shiny appearance was caused by the vitrification of the victim’s brain due to intense heat followed by rapid cooling.

Speaking about this process, Petrone said: “The brain exposed to the hot volcanic ash must first have liquefied and then immediately turned into a glassy material by the rapid cooling of the volcanic ash deposit.”

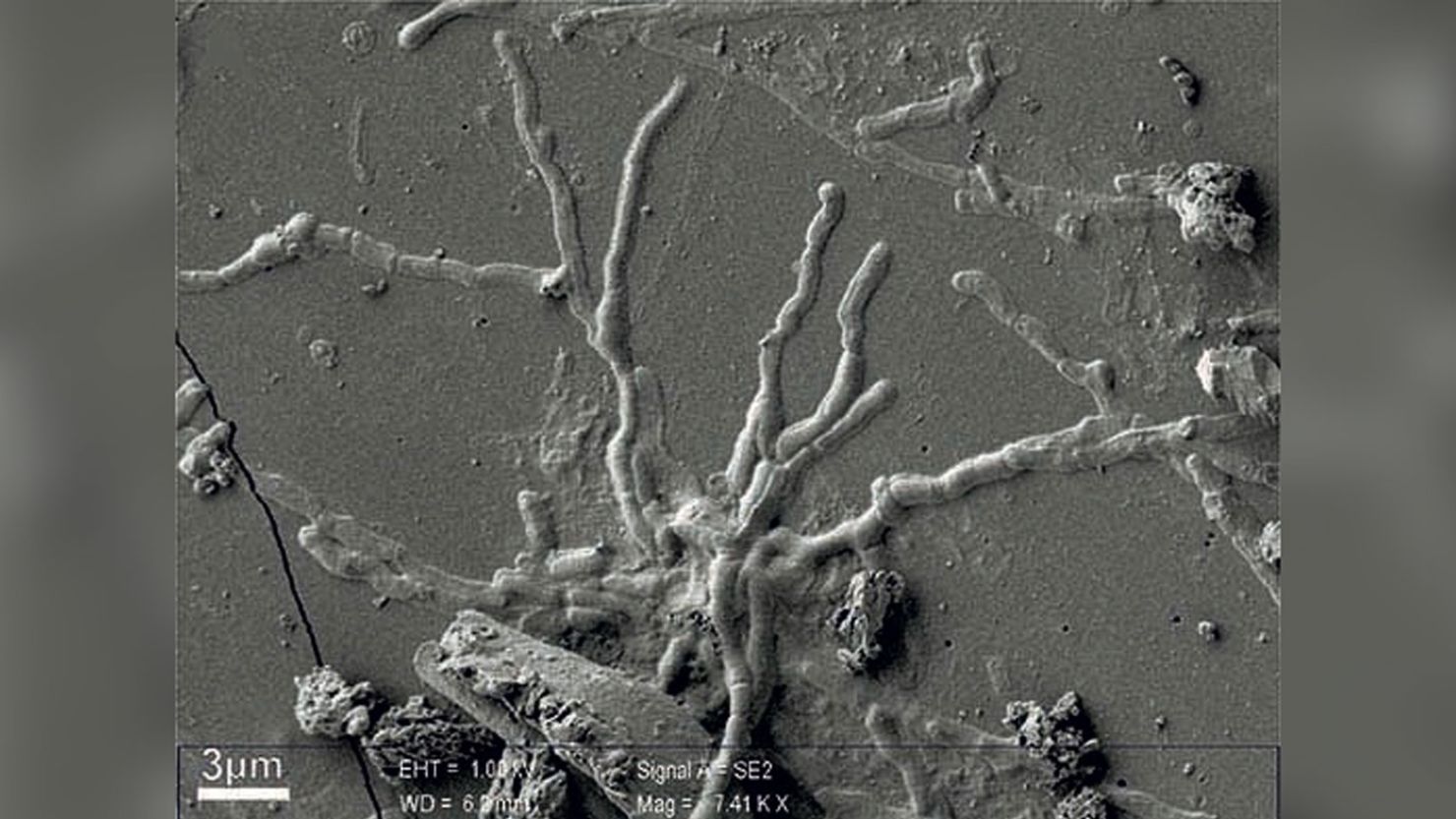

After subsequent analysis including the use of an electron microscope, the team found cells in the vitrified brain, which were “incredibly well preserved with a resolution that is impossible to find anywhere else,” according to Petrone.

The researchers also found intact nerve cells in the spinal cord, which, like the brain, had been vitrified.

The latest findings were published in the American journal PLOS One.

Guido Giordano, a volcanologist at Roma Tre University who worked on the study, told CNN that charred wood found next to the skeleton allowed the researchers to conclude that the site reached a temperature of more than 500 degrees Celsius (932 degrees Fahrenheit) after the eruption.

Referring to the latest findings, Giordano said the “perfectness of preservation” found in vitrification was “totally unprecedented” and was a boon to researchers.

“This opens up the room for studies of these ancient people that have never been possible,” he said.

The team of researchers – archaeologists, biologists, forensic scientists, neurogeneticists and mathematicians from Naples, Milan and Rome – will continue studying the remains.

They want to learn more about the vitrification process – including the exact temperatures victims were exposed to, as well as the cooling rate of the volcanic ash – and also hope to analyze proteins from the remains and their related genes, according to Petrone.

The former task is “crucial for the evaluation of the risk by the relevant authorities in the event of a possible future eruption of Vesuvius, the most dangerous volcano in the world, which looms over 3 million inhabitants of Naples and its surroundings,” Petrone said.