More than 160 human rights groups around the world have signed a letter calling for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to reverse its decision to hold the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, citing allegations of widespread rights abuses by the Chinese government.

The letter, which is addressed to IOC president Thomas Bach, and signed by human rights organizations on every continent, said that the actions of the Chinese central government in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong and Inner Mongolia showed the country was unworthy to host the Winter Olympics.

“The IOC’s reputation was indelibly tarnished by its mistaken belief that the 2008 (Beijing Summer) Olympics would work to improve China’s human rights record. In reality the prestige of hosting the Olympic Games merely emboldened the Chinese government’s actions,” the letter said.

“We implore the Committee to reverse its past mistakes and to urgently demonstrate that it has the political will to abide by the Olympic Charter’s core principles about ‘human dignity.’ The IOC must not allow its moral authority to be put in jeopardy again.”

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said at a news conference in Beijing Wednesday that the letter was attempting to “politicize” sports, a move which China “firmly opposes.”

In a statement to CNN, the IOC said that they remained neutral on political issues, and that awarding the Olympic Games “does not mean that the IOC agrees with the political structure, social circumstances or human rights standards in its country.”

The IOC said in 2017 that it would add human rights, anti-corruption and sustainable development clauses to Olympic Host City contracts in the future, beginning with the 2024 Summer Games.

Calls to boycott the 2022 Winter Olympics have become increasingly mainstream, with US Democratic presidential candidates asked about whether the US should send a team to the upcoming Games during a debate in December 2019.

Former vice president and 2020 US Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden didn’t respond to the question.

Olympic prestige

China hosted the Summer Olympics for the first time in 2008 in Beijing, which many saw as the country’s arrival onto the world stage as a major economy and aspirational superpower.

The ruling Chinese Communist Party poured enormous amounts of money and effort into ensuring the games were a success, despite concerns at the time around the country’s human rights record, including from then US President George W Bush.

Yaqiu Wang, a China researcher with Human Rights Watch, said that holding a prestige event like the Olympics was a source of “enormous pride” to the Chinese government. “(The 2008 Olympics) gave them a way to legitimize their human rights abuses, it’s like a reputation laundry for Beijing,” she said. Human Rights Watch was not a signatory to the letter calling for the 2022 Games to be taken away from Beijing.

In 2015, Beijing was awarded the 2022 Winter Olympics, meaning it’s set to become the first city to host both the Summer and Winter Games. Only Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan, were in the running for the 2022 Games, after Oslo, Munich and Stockholm pulled out.

Asked about concerns over human rights issues in both China and Kazakhstan at the time, IOC president Bach told CNN that the IOC’s role was “to ensure that during the games, and for all the participants, the Olympic charter applies.”

“That means tolerance, no discrimination (and) understanding dialogue,” he said.

But since 2015, the Chinese government has faced growing criticism due to allegations of human rights abuses, especially over its mass detention of Muslim citizens in Xinjiang and the erosion of civil liberties in Hong Kong.

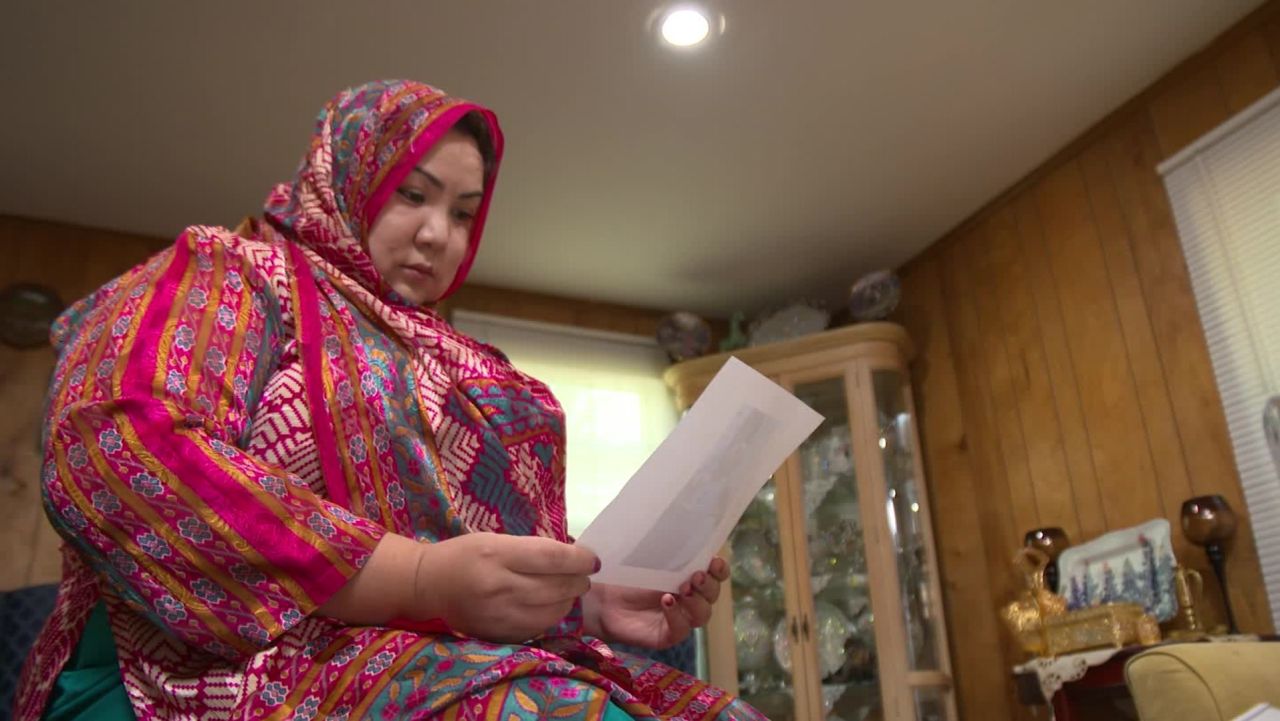

Up to 2 million Muslim minorities in the western Xinjiang region have been detained inside enormous re-education facilities, according to the US State Department. Reports have emerged from inside the camps of abuse, indoctrination and mass birth control.

The Chinese government has defended its policy in Xinjiang as a deradicalization program, and said the camps are “vocational training centers” where Muslim minorities can voluntarily learn life skills and the Chinese language.

Meanwhile in Hong Kong, the Chinese government imposed a new national security law in June, which activists say severely curtails freedom of speech and other human rights, in the wake of the months-long pro-democracy protests in the city through 2019.

Opposition lawmakers and businessmen critical of Beijing have already been arrested in Hong Kong in the wake of the new law coming into effect. The Hong Kong government and Chinese authorities have defended the law, saying it has stabilized the city.