Before long-necked dinosaurs like Brontosaurus grew into their giant bodies, they began as baby dinosaurs with some unusual facial features that changed as they aged, according to a new study.

Those features include eyes much like humans – positioned in the front of the head – instead of on each side as they are in adults, as well as a rhino-like horn.

“We expect that the specimen will become one of the most important fossils in the study of reproduction and development of the gigantic quadrupedal dinosaurs,” said Martin Kundrát in an email, study author and head of the PaleoBioImaging Lab at Pavol Jozef ?afárik University in Slovakia.

This group of dinosaurs, known as titanosaurian sauropods, were known for their long necks and tails and small heads and included the largest terrestrial animals that ever walked the Earth. Understanding their tiny origins, small enough to fit inside an egg the size of an ostrich egg, would shed light on how they grew and developed.

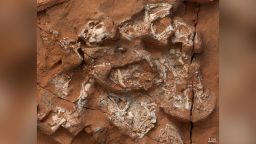

And 25 years ago, researchers hit pay dirt in their quest when they discovered a Cretaceous nesting ground of these dinosaurs in the eroded badlands of Auca Mahuevo in Patagonia, Argentina – a site where titanosaurian sauropods once laid their eggs 80 million years ago.

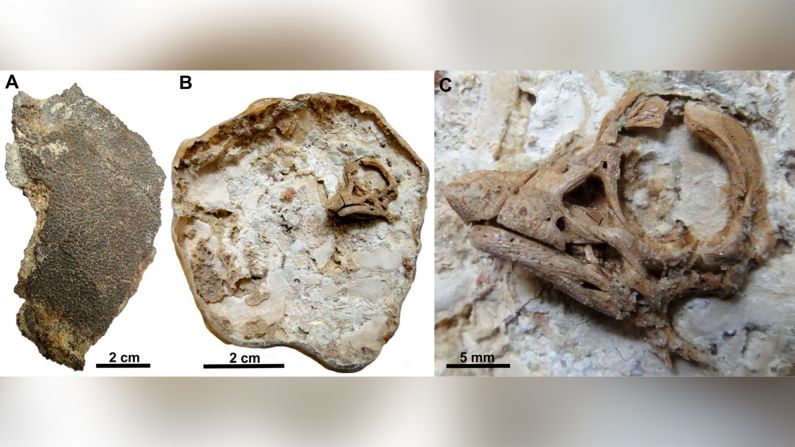

But the eggs researchers discovered at that site were flattened, making the study of a three-dimensional skull difficult.

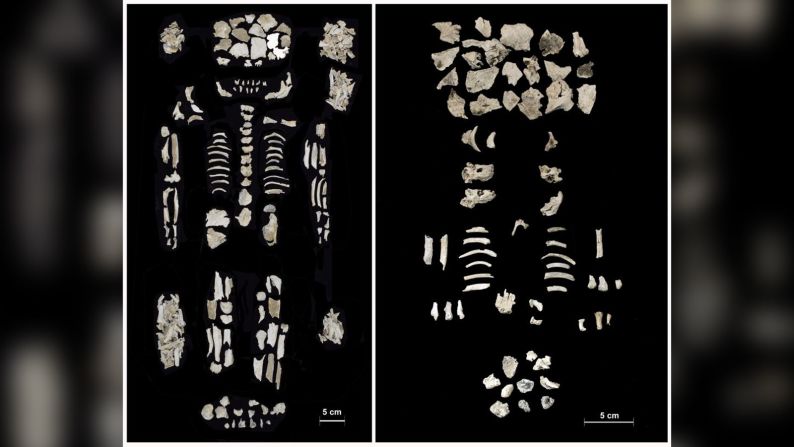

A new study focused on what researchers are calling the first discovery of a nearly intact embryonic skull of a titanosaurian sauropod. The skull remains three-dimensional enough to contain intriguing details, like the unexpected, specialized facial features these hatchlings possessed.

The study published Thursday in the journal Current Biology.

Synchrotron microtomography, a powerful new imaging technology, helped researchers peer inside the very structure of the embryo’s teeth, bones and evidence of soft tissues, like calcified remnants of the dinosaur’s braincase and jaw muscles and even tiny teeth in the jaw sockets.

“The preservation of embryonic dinosaurs preserved inside their eggs is extremely rare,” said John Nudds, study couathor and palaeontology professor at The University of Manchester, in a statement. “Imagine the huge sauropods from ‘Jurassic Park’ and consider that the tiny skulls of their babies, still inside their eggs, are just a couple of centimetres long.”

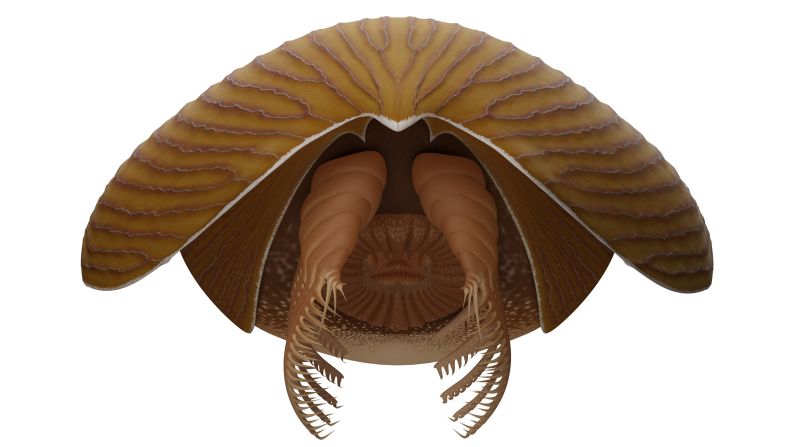

Based on their scans of the fossil, the researchers could essentially look inside the egg and determine what this hatchling looked like – and the peculiar face looking back at them wasn’t what they expected.

Inside the egg

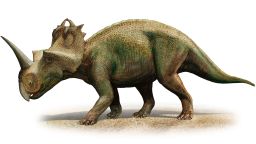

When they hatched, the titanosaurian babies had retracted openings on their nose, a small single-horned face and binocular vision – where the eyes are oriented in the same direction and can capture a single 3D image – like humans.

The little horn may have helped the baby dinosaur break out of its shell.

The dinosaur’s head and face would change as it grew and developed into an adult. This vision and single horn haven’t been observed in adults – although the researchers don’t rule out that this could potentially be a previously undiscovered species.

Currently, it’s most similar to a titanosaurian dinosaur that lived during Upper Cretaceous in Brazil called Tapuiasaurus, between 66 million and 100.5 million years ago.

While the embryonic dinosaur is also from Patagonia, the researchers don’t know where it was found precisely because the egg was illegally exported from Argentina. When the researchers learned this, study coauthor Terry Manning ensured the fossil would be sent back to Argentina. Currently, it can be found with the embryos discovered at Auca Mahuevo at the Museo Municipal Carmen Funes in Plaza Huincul.

This specimen differs from the other embryonic dinosaurs found in Patagonia in that it was found inside an egg with a much thicker shell. The skull was also 30% smaller than the skulls recovered from Auca Mahuevo, but the cranial bones “had already reached almost identical completeness.”

The skull has shown that this hatchling used calcium derived from inside the eggshell long before it was ready to hatch. Combined, these findings suggested changes in the timing of the developmental process.

The unusual features of this hatchling also suggested it lived in a different habitat and different conditions, but the researchers won’t know more until they discover other examples of this in the fossil record.

But, Kundrát speculated, given that there is no evidence of parental care in titanosaurian dinosaurs, these babies were likely on their own for food and defense once they hatched.

(Sorry, “Land Before Time” Littlefoot fans out there – it looks like it didn’t have a mother’s love.)

“They could stay hidden in a forest-like habitat before they got big enough to move to an open environment,” Kundrát said. “Good sight and binocular vision could provide an advantage in food detection as well as potential danger. The most striking feature, the premaxillary horn, could be used in search for a food or/and as a defense tool for the period when there were most vulnerable.”

As these babies grew into adult titanosaurians, their vision likely changed as their eyes moved laterally to the sides of the head. It’s also possible that their snout and face grew faster than their braincase, which could essentially get rid of the horn – but all of this is hypothetical and more examples are needed, Kundrát said.

He is hopeful to study more embryonic dinosaurs in the future and understand how they evolved into giants.

“Dinosaur eggs are for me like time capsules that bring a message from the ancient time,” he said. “This was the case of our specimen that tells a story about Patagonian giants before they hatched.”