If the world does nothing to mitigate sea level rise, coastal flooding will become so extreme and destructive that it could cause damage worth up to 20% of global gross domestic product by 2100, according to new research.

The study, published Thursdayin the journal Science Reports, is the first to map the projected economic impact of sea level risecaused by the climate crisis.

The authors say rising sea levels could cost the global economy $14.2 trillion in lost or damaged assets by the end of the century, as larger areas of land, home to millions of people, are inundated.

“This is on a ‘business as usual’ CO2 emissions scenario,” said Ebru Kirezci, from the University of Melbourne, who led the study.“Business as usual” assumes a rise in average global temperatures at the upper end of predictions, if global emissions are allowed to continue on their current course.

As temperatures and sea levels rise,the study estimates that as many as 287 million people could be exposed toepisodic coastal flooding by 2100 – up from a maximum 171 million today. More than one million square kilometers of coastline could also be compromised – an area almost twice the size of France.

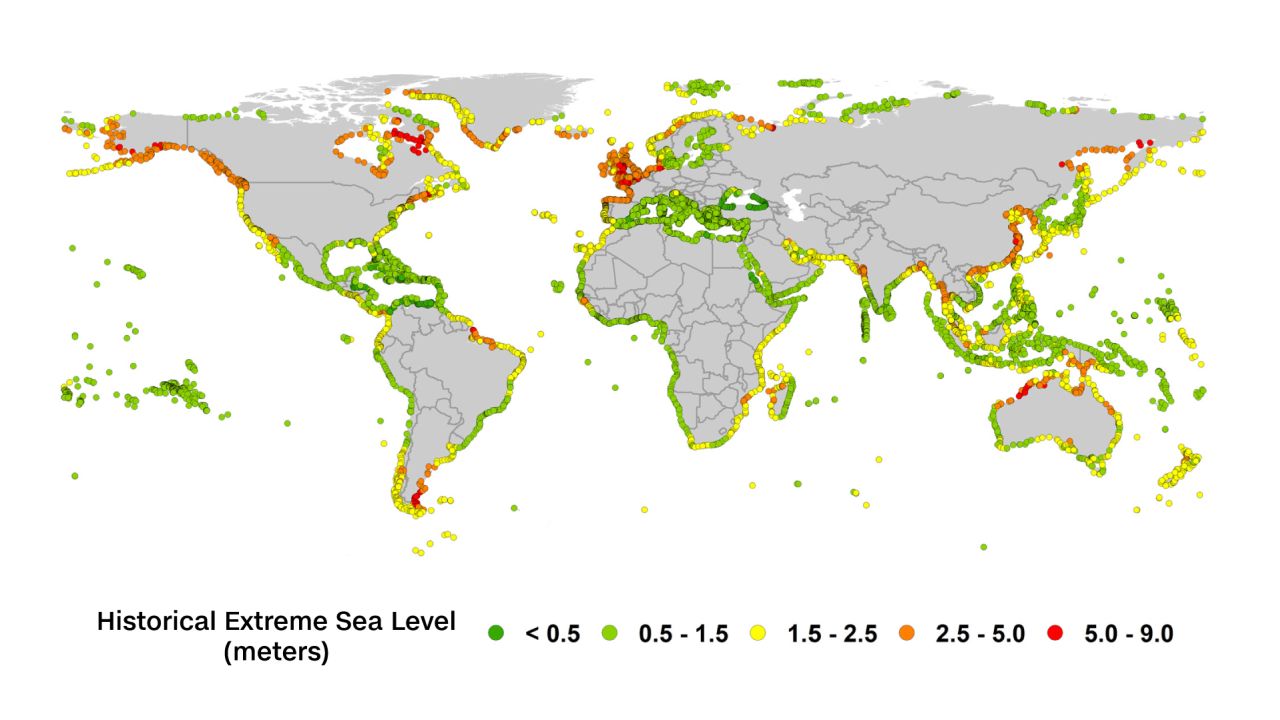

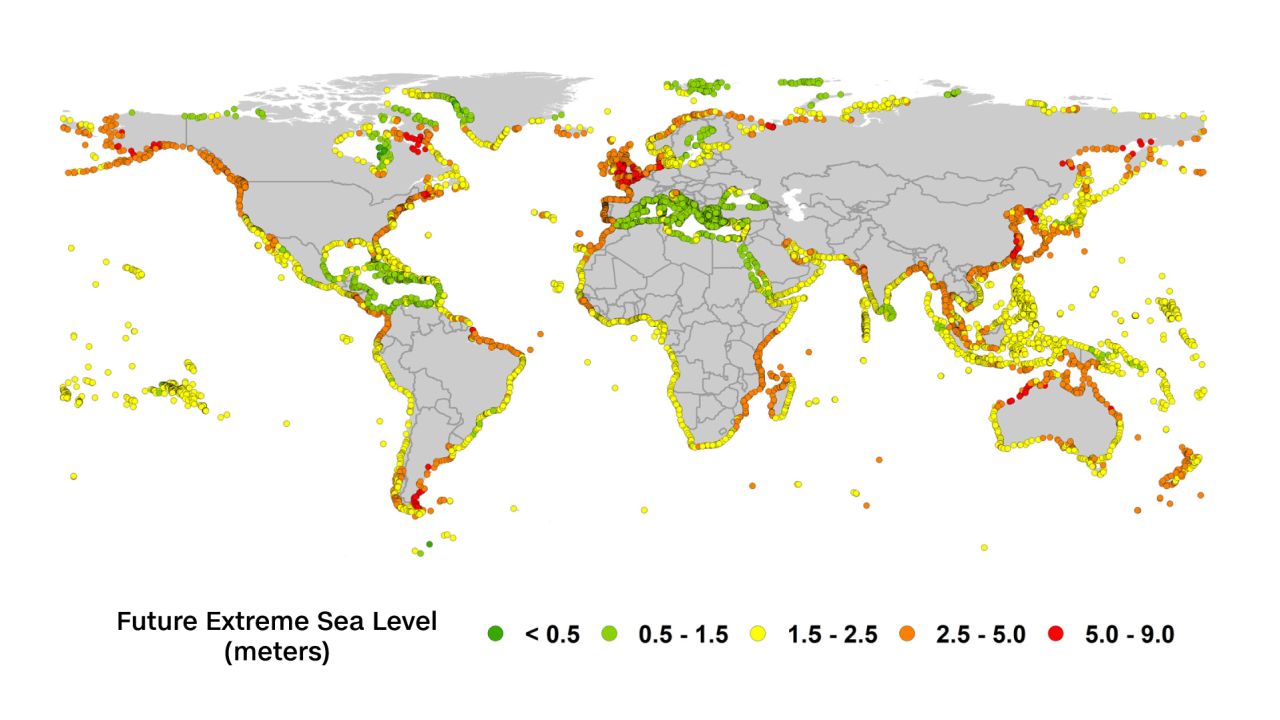

Areas most at risk of extensive flooding include the northeastern coast of the United States, northwestern Europe, and large parts of Asia – including countries around the Bay of Bengal, Indonesia, China, and northern Australia, according to the authors.

Some of the mostvulnerable areas are heavily-populated, low-lying and low-income regions that already deal with devastating annual flooding.

The authors say their figures don’t take into account coastal defenses or predicted increases in the global economy or population by 2100. However, they say putting a dollar figure on the worst case scenario could spur policy change before it’s too late.

“If you want politicians to take notice, you have to put it into terms that resonate for them. The terms that resonate for them are economic impacts,” said Ian Young, Kernot Professor of Engineering at the University of Melbourne, and co-author of the study.

All about extremes

Instead of focusing on the mean – or average – rise in sea levels, the study looks at sea levels during extreme storms over the past 30 years to model the maximum area that could be at risk of flooding.

They took this route because flooding or beach erosion is most likely to happen during a storm, they said.

They mapped all of the “one in 100-year” flooding events – particularly the destructive storm surges and flooding that result from intense storms and cyclones – onto the world’s coastlines. Combining this data with projections of sea level rises under different greenhouse gas emission scenarios, the authors modeled maximum increases in sea levels.

“We are looking at extremes,” said Young. “Being able to model the tide, storm surge, wave set up, sea level rise, the extremes that that generates, and to do it on a global scale – that’s what is unique about this project.”

Sea levels are rising because greenhouse gas emissions are warming the oceans and planet, melting polar ice caps and glaciers.

If nothing is done to reduce carbon emissions by 2100, vulnerable areas that are at risk from a “one in 100-year” flooding event, will experience them once every decade, the authors found.

“We are already seeing increased frequency of storm surges and extreme sea levels,” said Kirezci. “The risks are increasing and climate change exacerbates these impacts.”

To reach the economic cost of more major floods, the researchers combined their model with topographic data to identify areas at risk of coastal flooding, as well as mapping that onto population data and the GDP in those affected areas.

“Our main goal with the study was to inform the decision makers and policy makers around the world so we can identify the hotspots – the most vulnerable areas – across the global coastlines,” said Kirezci.

What that means for countries and vulnerable populations

Severe flooding already costs billions of dollars every year in damage, as houses, buildings and vital infrastructure like roads, pipes and electricity pylons farms and croplands are destroyed.

Flooding is now the most common and costly natural disaster in the US, causing some $155 billion in property damage in the last decade. Last year, many parts of the Midwest and South were swamped by flood waters that lingered for months and caused $6.2 billion in damage and four deaths, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In Asia this year, millions of people in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, China and Japan are dealing with some the worst flooding in decades following unrelenting monsoon rains. In India’s eastern states of Assam and Bihar, raging flood waters have inundated thousands of villages, killing more than 100 people and affecting almost 4 million.

In China, devastating floods have impacted at least 38 million people in 27 of the country’s 31 provincial regions since June, and in some places, water levels have reached perilous heights not seen since 1998, when massive floods killed more than 3,000 people.

Kirezci’s study suggests those social and economic costs will only get worse if calls to build more flood defenses are ignored.

“As with many environmental issues, it’s the poor that are impacted most,” said Young. “The real humanitarian challenge will be what you do. Can you actually afford to build coastal defenses, do you have to relocate populations, how would you actually go about that?”

The scientists say that even if we reduce greenhouse gas emissions now, some sea level rise isinevitable.

“Irrespective of what we do with changing our climate, those sea level rises are going to occur,” Young said.

As well as reducing emissions, countries should invest in adaptation measures to protect against future flooding, researchers say. Those include building up natural defenses such as mangroves and sea grasses that absorb waves and surges along coastlines, as well as beach nourishment – where sands are moved to bolster beaches and dunes.

As a last resort, the researchers say, entire populations may have to be moved away from the coast, an expensive and highly disruptive move that could cause huge humanitarian issues.

Kirezci said people should be aware of the climate crisis’ impact on sea levels. “We need to raise awareness of coastal communities, which are residing in the low-lying areas,” she said.