Chief Justice John Roberts did not flinch.

When Roberts joined liberals on the Supreme Court to preserve an Obama-era program shielding young undocumented immigrants who came to the US as children, he surprised some of his colleagues by voting against the Trump administration from the beginning, according to multiple sources familiar with the inner workings of the court.

About this series

New details obtained by CNN reveal how Roberts maneuvered on controversial cases in the justices’ private sessions, at times defying expectations as he sided with liberal justices. Roberts exerted unprecedented control over cases and the court’s internal operations, especially after the nine were forced to work in isolation because of Covid-19.

The chief justice, for the first time in his tenure on the court, voted to strike down a state law that would diminish access to abortion and, in a decision for the ages, rejected President Donald Trump’s extensive claims of “temporary presidential immunity.”

Roberts also sent enough signals during internal deliberations on firearms restrictions, sources said, to convince fellow conservatives he would not provide a critical fifth vote anytime soon to overturn gun control regulations. As a result, the justices in June denied several petitions regarding Second Amendment rights.

In an exclusive four-part series, CNN offers a rare glimpse behind the scenes at how justices on the Roberts court asserted their interests, forged coalitions and navigated political pressure and the coronavirus pandemic. The justices’ opinions are public, but their deliberations are private and usually remain secret.

More in this series

Overall, Roberts was in the majority on the nine-member bench more than any other justice this session, meaning his views prevailed most in the justices’ private sessions. He used the full power of his position as chief and his place at the ideological middle to shape decisions. And in one instance, Roberts wrested the majority opinion away from a colleague, Justice Clarence Thomas, during the internal opinion-drafting process after votes were taken, according to sources.

As he closed out his 15th term in the center chair, Roberts demonstrated a new ability to calibrate his views and build coalitions. He sided with liberals in some major disputes, yet reinforced his conservatism on religion, voting rights and executive authority over independent agencies

He also finished the session with a health scare – one he initially tried to keep hidden from the public. Just as the session was ending, he fell while at a country club near his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland, hit his head and had to be taken by ambulance to a hospital. Roberts did not publicly reveal the June 21 incident for more than two weeks, and then only after The Washington Post followed up on a tip. A court spokeswoman said doctors attributed the fall to light-headedness caused by dehydration as he was walking and that it was not the result of a seizure, as had happened to Roberts on two prior publicly revealed occasions.

Throughout the term, Roberts continued to draw the predictable wrath of Trump and some Republicans who believe the 2005 appointee of President George W. Bush betrayed the conservative cause. For his part, Roberts appeared to grow increasingly impatient with Trump’s legal positions.

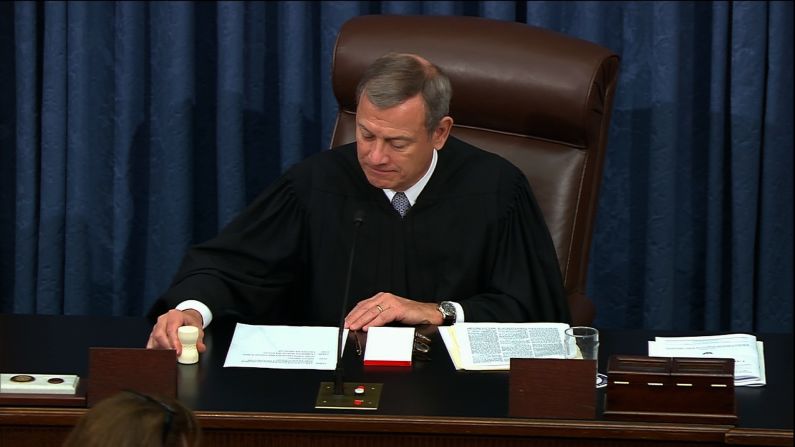

Roberts’ year began with heightened drama that reinforced his position as a gatekeeper of sorts for Trump actions. For three weeks, from late January into February, Roberts presided over the Trump impeachment trial. He oversaw the proceedings, which often went late into the night, on the elevated Senate dais.

He was in the public eye far more than usual during the televised hearings, which ended in Trump’s acquittal. But as much as the chief justice was visible then, it is actions from his Supreme Court perch that make a difference in American life.

Roberts is only 65 and could serve 20 more years. Yet this session and his action on some of the Trump administration’s most visible policy moves will go a long way toward defining his legacy.

How Roberts decided to save DACA

Roberts’ June decision saving the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program surprised advocates on both sides and even took some colleagues aback when he had first cast his vote many months earlier in private session, sources told CNN.

Roberts had generally supported Trump’s immigration policies, and in 2016 had privately voted against a related program for parents, rather than children, who had come to the US without papers, sources said. (That case, United States v. Texas, produced a 4-4 vote behind the scenes, after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, and no resolution on the merits.)

But the new reporting reveals that unlike Roberts’ 2012 move to uphold Obamacare and separate 2019 action to ensure no citizenship question on the 2020 census, Roberts’ action on DACA was not a late vote switch. He put his cards on the table soon after November oral arguments in the case and did not waver, sources told CNN. Roberts believed the administration had not sufficiently justified the rescission of the program benefiting some 700,000 young people and had then developed after-the-fact rationalizations.

Trump announced in September 2017 that he was ordering an end to the program that shielded undocumented immigrants who came to the US as children from deportation and allowed them work permits. California, New York and other states, along with the Regents of the University of California and immigrant rights groups, challenged the Trump action, saying the administration had not followed federal procedures regarding the phaseout of a program.

The coronavirus pandemic, which seized most of America in March, heightened the potential consequences for DACA beneficiaries, the people who employ them and the people they care for. An estimated 27,000 DACA recipients work in the health care field, as nurses, physician assistants and home health aides, according to filings in the case.

But by the time Covid-19 concerns were at the fore, Roberts was already writing an opinion that would protect DACA beneficiaries for now. He finished his first draft in late March. Three of the liberals responded enthusiastically to the draft opinion, CNN has learned, and asked for only minor changes.

The fourth, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, held off somewhat. She said she would join Roberts on much of the 5-4 judgment but expressed dismay that the chief had foreclosed a possible equal protection violation based on Trump’s racist comments about Mexican immigrants. She soon sent around a draft opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part.

Among the Trump declarations Sotomayor cited in her final opinion: that Mexican immigrants are “the bad ones” and “criminals, drug dealers, [and] rapists.” The court’s first Latina justice also noted that Trump had compared undocumented immigrants to “animals.”

Roberts was ready to give the administration another opportunity to properly phase out the DACA program, and liberals were not opposed. The question, after all, was not whether the Trump administration could end DACA, it was whether it had fulfilled the requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act, which forbade arbitrary and capricious actions.

In Roberts’ opinion, he emphasized that the Department of Homeland Security had failed to sufficiently consider the potential hardships for those who were relying on the DACA program.

In 2019, Roberts had relied on Administrative Procedure Act standards when he rejected Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’ attempt to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census. But in that dispute, the chief justice had come to his determination against Ross’ contrived reasoning late in the court’s internal deliberations.

Roberts’ winning streak extended to a Georgia copyright dilemma, heard in December, when he was able to turn his dissenting opinion into the prevailing view during the drafting process. He captured the majority from Thomas, who had initially taken control of the case once votes were cast in their private session after oral arguments.

The Georgia case decided in April, testing whether a state can copyright its annotated legal code, was not a high-profile one. But it offered an example of the rare but consequential vote-shifting that can occur behind the scenes and make a difference in the outcome of a case and law nationwide.

The court ruled that federal copyright protections do not cover annotations in a state’s code, based on the general principle, Roberts wrote, “that no one can own the law.”

Blocking conservatives on the Second Amendment

Among the many mysteries of the recent session is why the conservative justices stopped pressing for a new firearms case that would allow them to bolster Second Amendment rights.

After hearing a New York City gun regulation challenge in December, the majority decided the case was moot because the city had amended its ordinance which banned the transporting of guns to firing ranges or second homes outside the city.

CNN has learned that resolution of that case took many twists and multiple draft opinions. Guided by Roberts, Justice Brett Kavanaugh crafted much of what turned out to be an unsigned “per curiam” opinion – joined by six justices, including Roberts – returning the case to lower court judges. Kavanaugh also wrote a separate statement – this one he signed – suggesting it was time for the justices to resolve conflicting interpretations of Second Amendment rights.

Challenges to other firearms regulations were pending and conservatives who had wanted to clarify the scope of the Second Amendment had to consider whether to bring the issue back to the justices.

It takes four votes to accept a case and five to rule on it, and sources have told CNN that the justices on the right did not believe they could depend on a fifth vote from Roberts, who had in 2008 and 2010 voted for milestone gun-rights rulings but more recently seemed to balk at the fractious issue.

In mid-June, the high court turned down petitions from 10 challenges to state laws limiting the availability of firearms and when they can be carried in public.

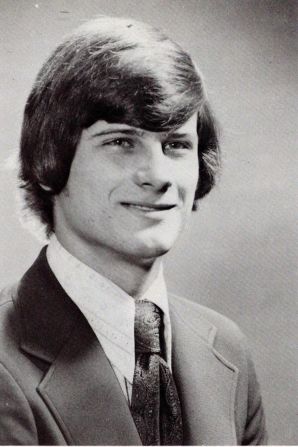

In photos: Chief Justice John Roberts

The action perplexed court observers who had believed the right-wing majority was eager to further elucidate the 2008 landmark District of Columbia v. Heller. Some conservative justices indeed wanted to take up the issue, but they apparently could not count on a majority.

Not only was Roberts, with his new position at the middle of the bench since the 2018 retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, controlling how cases were decided, he also was influencing what cases were even taken up.

Keeping the liberals at bay

Roberts’ decision in the DACA controversy represented a departure for the chief justice on Trump immigration practices. He had given the administration great leeway, beginning with his 2018 opinion, joined by fellow conservatives, upholding the Trump travel ban aimed at majority-Muslim countries.

In January, the same five-justice Roberts majority permitted the administration to proceed with a new income-related test for immigrants seeking green cards. The “public charge” rule denies permanent legal status to those applicants who even occasionally apply for Medicaid, food stamps or certain other public assistance.

Three months later, amid a new dilemma over the rules arising from the Covid-19 virus, Roberts took the lead against immigrant interests yet mollified liberals poised to dissent publicly, CNN has learned.

New York state officials in April implored the court to lift or modify its January order, arguing that the policy was deterring immigrants from accessing public health and medical benefits to prevent or treat Covid-19.

According to sources, liberal justices believed the pandemic had transformed the situation and wanted the administration to clarify its rules to help places like New York hit hard by the virus in the spring. Roberts was unmoved and believed administration guidance was clear that immigrants could obtain Covid-19 care without consequence to their green-card applications. Other conservative justices agreed.

Liberal justices wrestled with how far to go with their contrary view and whether to publicly dissent, CNN has learned from inside accounts. Some justices also worried that if the request were rejected, the high court would appear to be unconcerned about people getting sick from the coronavirus.

Just a few weeks earlier in a Wisconsin election dispute, the five-justice conservative majority brushed away public safety concerns and sided with the Republican National Committee and Wisconsin GOP to restrict ballots-by-mail. The court’s order was issued the night before the April 7 election and as state officials had a backlog of absentee ballot requests pending.

“In the weeks leading up to the election, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a public health crisis,” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote, joined by the three other liberal justices. She noted that the pandemic had caused a late surge in requests for absentee ballots. “The Court’s order, I fear, will result in massive disenfranchisement.”

As liberal justices were again losing the argument, they wanted to offer some signal to the New York challengers that they could keep making their case in a lower court even as the Supreme Court ruled against them.

Roberts resisted, CNN has learned. But the chief justice had an interest in tamping down the tensions and agreed to a modest compromise that sent the signal the liberals sought in the court’s order and ensured that the challengers were not prevented from pressing ahead.

Covid-19 gives Roberts more power

Roberts’ power over their internal operations increased, too, as the justices were relegated to telephone and email communications. The court declined to use any Zoom-like option for its meetings, according to sources, so for the past four months the justices have not seen one another, even virtually. Roberts decided they would conduct arguments by phone when in-courtroom arguments were canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

That decision caused some internal grumbling, CNN has learned, about the format and over how much time each justice would get to question a lawyer. Roberts ended up allowing each justice three minutes.

To avoid possible confusion about who was talking during the phone sessions, Roberts decreed they would ask questions in order of seniority, beginning with himself. During the regular in-courtroom sessions, the justices’ questions are rapid-fire. With little regard for order, they pound away at weaknesses in the lawyers’ positions, highlight points that interest them and try to make their own cases to colleagues.

Roberts carefully outlined the timing for the advocates and justices who would be connected by telephone. The plan was similar to an arrangement used a week earlier by a US appeals court in Washington for a nine-judge hearing.

More in this series

The chief justice thought there would even be sufficient time after justices had taken their turns for a round of open questioning.

For that final round, he said, if anyone wanted to ask a question, he or she could try to break in. He encouraged them to be brief.

The chief recognized that several justices might jump in at once. If that happened, he said, he would call on one of them to speak.

If he mistakenly called on a justice who was not trying to break in, he had a fix for his colleagues:

Try to ask a question anyway.

But on one question there was no doubt: John Roberts was in charge.