Early human ancestors used advanced techniques to craft a handaxe from the femur of a hippopotamus 1.4 million years ago, according to a new study.

While stone handaxes have been recovered in the past, a handaxe made from bone during this time is incredibly rare. Only one other bone handaxe has been recovered from this time period, according to the researchers.

Bone handaxes have also been recovered in Italy, Tanzania, Hungary and Germany, but they are more recent, dating from 260,000 to 500,000 years ago.

This bone handaxe was recovered in southern Ethiopia at the Konso Formation, a site where researchers have previously discovered stone artifacts that reveal “considerable technological progression” between 1 million and 1.75 million years ago.

During the Pleistocene epoch between 11,700 and 2,580,000 years ago, early human ancestors created tools from stone, and based on this evidence, occasionally bone. These handaxes have a signature style, often oval or pear-shaped, referred to as Acheulean. This particular handax is considered to be an example of the Early Acheulean style.

These Acheulean tools are associated with Homo erectus, who lived between 110,000 and 1.89 million years ago, and Homo sapiens. Homo erectus, who had larger brains than previous Homo species and early human ancestors, were known for making and using tools.

The bone handaxe was discovered during field work in fall 1994, said Gen Suwa, lead study author and paleoanthropologist at the University of Tokyo. Suwa and his research team previously published work on the Konso site in 2013 and 2015. Then, they turned to the bone handaxe for a full analysis.

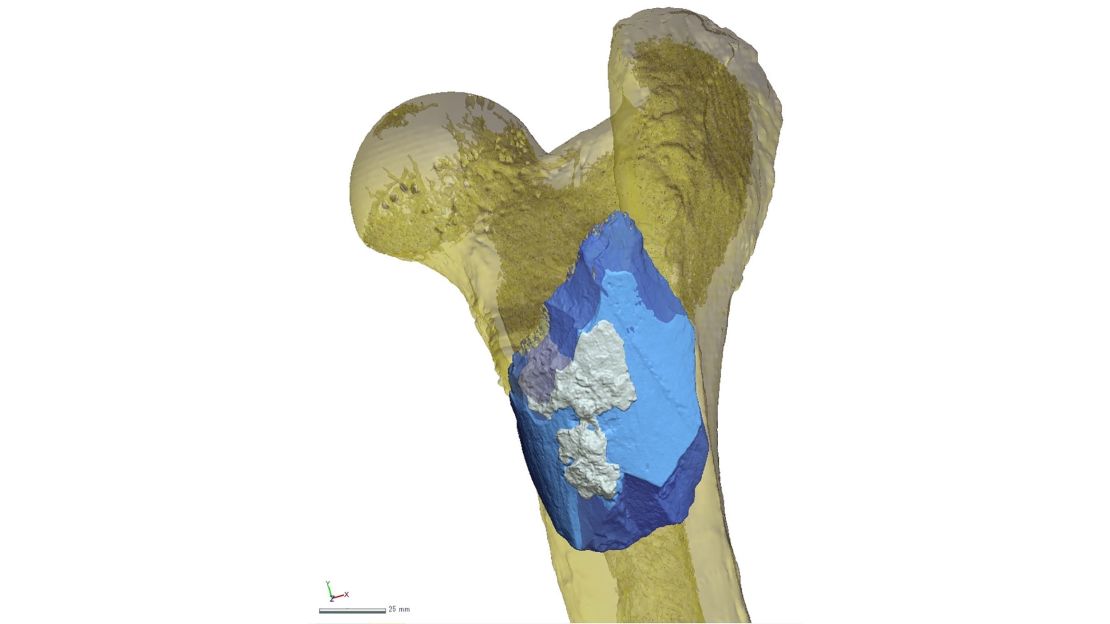

This particular handaxe, which is just over 5 inches long, shows advanced flaking techniques. Flaking involved the removal of flakes on stone or bone tools to create sharp edges for cutting, chopping or scraping.

The study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

On one side, the bone shows the surface of the original hippo femur. On the other side, there are multiple flaking “scars.” The scars near the tip of the handaxe showcase an alternating pattern, which suggests that someone was deliberately shaping the bone.

When the researchers analyzed the bone, they found wear and tear suggested by rounding on the handaxe’s tip and both sides, which may mean it was used to cut and saw. When the scientists studied the tool beneath a microscope, they also found ridges and polished areas that are similar to patterns they have found on stones that were used in butchering.

Given the fact that this is only the second bone handaxe recovered from this time period, the researchers can’t be sure of the materials this handaxe was used on. The previously discovered bone handaxe came from the fragment of a large limb bone, considered to be from an elephant, which was flaked into a handaxe-like form, according to the study.

But this newly discovered handaxe was shaped more than the previous one. All of the flaking provided a shaped tip and relatively straight edges, the researchers wrote in the study.

The researchers were surprised at the variety of techniques used to craft and shape this particular handaxe given the time when it was carved, Suwa said.

The craftsmanship of the tools at the Konso site, as well as other sites, “suggest that Homo erectus technology was more sophisticated and versatile than we had thought. And the bone handaxe occurrence fits in nicely,” Suwa said.

During the same time this handaxe was made, the environment where it was found was changing. The dry grasslands were shifting to include an expanding lake, as well as wet grasslands and woodlands later on. This attracted large mammals, like the ancestors of boars and buffaloes. Ancient human ancestors would have needed tools to hunt these large animals and process their carcasses.

This may have led them to refine their techniques so they could improve the process of making their tools.

“Despite the scarcity, discovery of the finely made Konso bone handaxe shows that refinement of flaking technology in the early Acheulean involved both stone and bone and provides additional evidence of the technological and behavioral sophistication of African Homo erectus through Acheulean times,” the researchers wrote in their study.