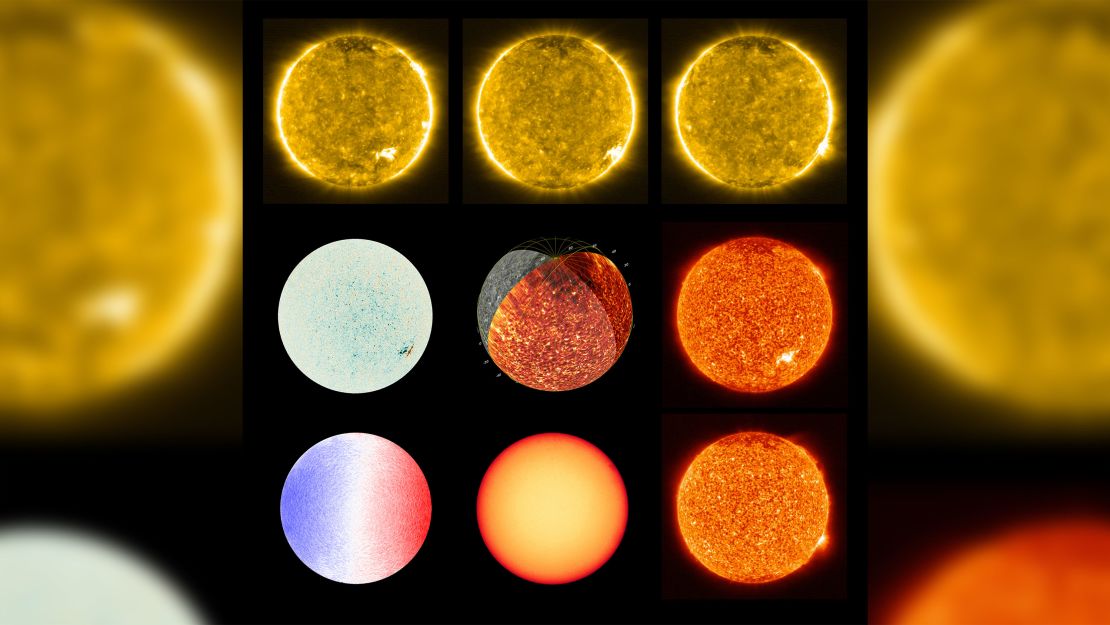

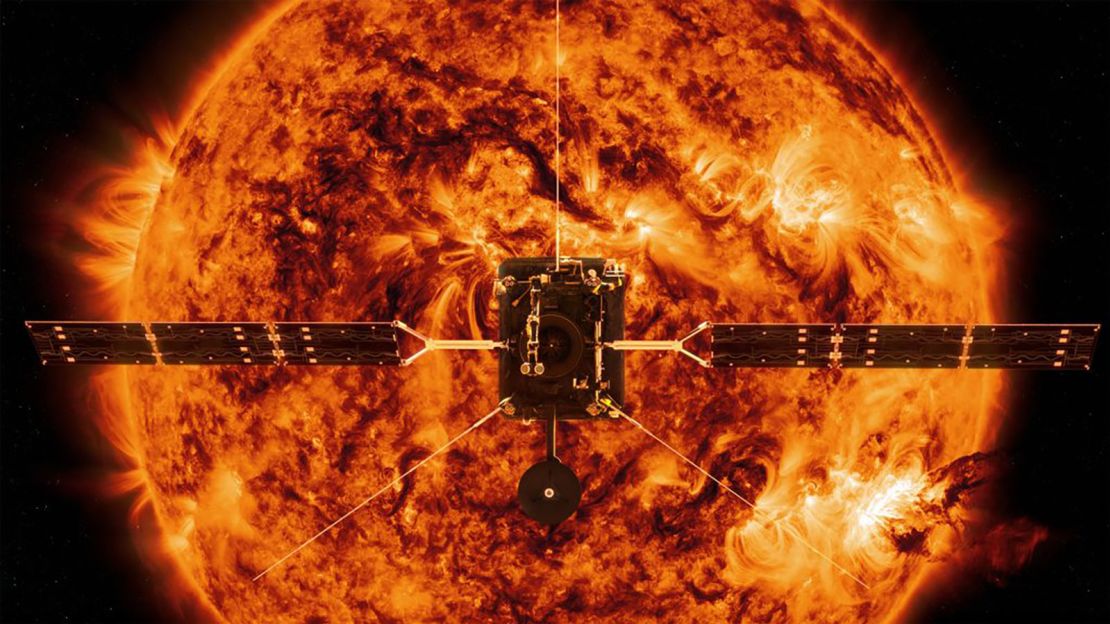

Our sun was ready for its close-up last month, and the new Solar Orbiter mission captured the closest images ever taken of the sun during its first pass. The images were released on Thursday.

The mission, which is a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency, launched in February and conducted a close pass of the sun in mid-June. All 10 of its instrumentswere switched on together for the first time during this pass to collect images and data.

The images were taken at a distance of 47,845,581 miles away from the sun. This close pass, which is called a perihelion, was within the orbits of the two closest planets to the sun, Venus and Mercury.

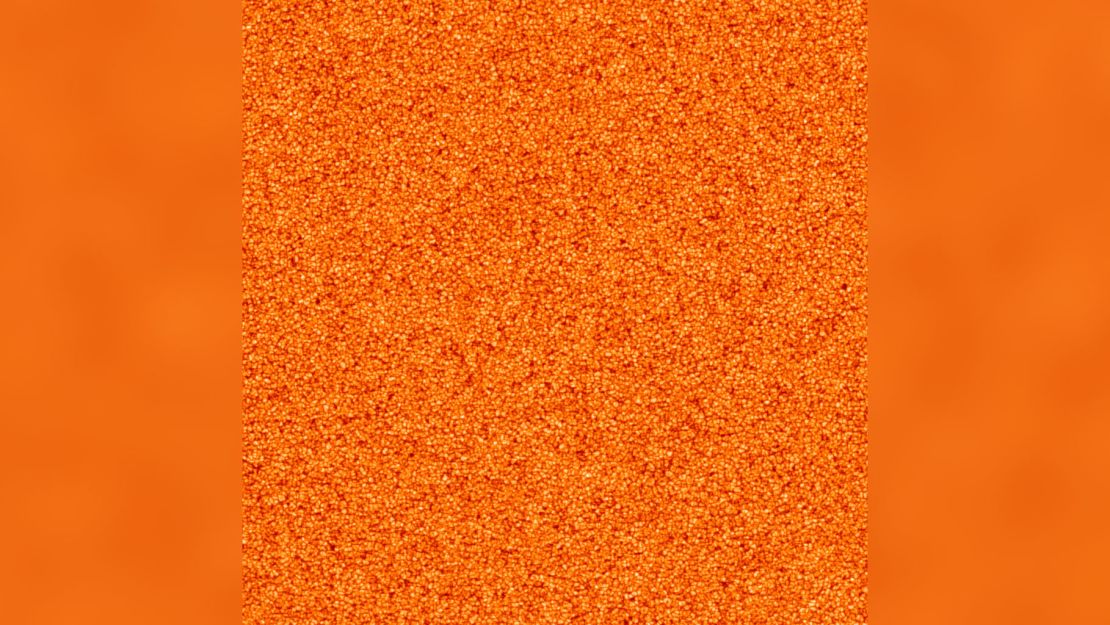

In the images, there are small solar flares called “campfires” that can be seen near the sun’s surface.

“No images have been taken of the Sun at such a close distance before and the level of detail they provide is impressive,” said David Long, co-principal investigator on the ESA Solar Orbiter Mission Extreme Ultraviolet Imager Investigation at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, in a statement.

“They show miniature flares across the surface of the Sun, which look like campfires that are millions of times smaller than the solar flares that we see from Earth,” he said.

“Dotted across the surface, these small flares might play an important role in a mysterious phenomenon called coronal heating, whereby the Sun’s outer layer, or corona, is more than 200 - 500 times hotter than the layers below,” Long said.

“We are looking forward to investigating this further as Solar Orbiter gets closer to the Sun and our home star becomes more active.”

The scientists don’t yet know what exactly the campfires are, but they believe they could be “nanoflares,” or tiny sparks that help heat the sun’s outer atmosphere.

“The campfires we are talking about here are the little nephews of solar flares, at least a million, perhaps a billion times smaller,” said David Berghmans, principal investigator of the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager and an astrophysicist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels. “When looking at the new high resolution EUI images, they are literally everywhere we look.”

Measurements of the temperature of these campfires could provide more information, something that the orbiter’s SPICE instrument, or Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment, can do.

In addition to images, data from the four instruments helping to measure the space environment around the orbiter was also shared.

“Already our data are revealing shockwaves, coronal mass ejections, phenomena called ‘switchbacks’ and fine-scale waves in the magnetic field that we are only able to see thanks to the extreme sensitivity of our instrument,” said Tim Horbury, principal investigator of Solar Orbiter’s magnetometer and professor at Imperial College London, in a statement.

Shortly after the mission launched in February, it was impacted by the shutdowns that occurred in response to the spread of coronavirus.

Mission control at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany to close down completely for more than a week during a time when each instrument was to be tested.

“The pandemic required us to perform critical operations remotely – the first time we have ever done that,” said Russell Howard, principal investigator for one of Solar Orbiter’s imagers.

But the team was ready just in time for the first close pass of the sun.

Two missions studying the sun

Solar Orbiter is the first mission that will provide images of the sun’s north and south poles. Having a visual understanding of the sun’s poles is important because it can provide more insight about the sun’s powerful magnetic field and how it affects Earth.

Solar Orbiter is equipped with 10 instruments that can capture observations of the sun’s corona (which is its atmosphere), the poles and the solar disk. It can also use its instruments to measure the sun’s magnetic fields and solar wind, or the energized stream of particles emitted by the sun that reach across our solar system.

Understanding the sun’s magnetic field and solar wind are key because they contribute to space weather, which impacts Earth by interfering with networked systems like GPS, communications and even astronauts on the International Space Station.

The sun’s magnetic field is so massive that it stretches beyond Pluto, providing a pathway for solar wind to travel directly across the solar system.

The mission will work in tandem with NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which is currently orbiting the sun on a seven-year mission and just completed its fourth close approach of the star. It launched in August 2018 and will eventually come within 4 million miles of the sun – the closest a spacecraft has ever flown by our star.

The Parker probe is “tracing the flow of energy that heats and accelerates the sun’s corona and solar wind; determining the structure and dynamics of the plasma and magnetic fields at the sources of the solar wind; and exploring mechanisms that accelerate and transport energetic particles,” according to NASA.

Together, the missions can help unlock the mysteries of the sun and provide more data to researchers than either could accomplish on its own. Parker can sample particles coming off the sun up close, while Solar Orbiter will fly farther back to capture more encompassing observations and provide broader context.

At times, the spacecraft will both align to take measurements of the solar wind or magnetic field.

“We are learning a lot with Parker, and adding Solar Orbiter to the equation will only bring even more knowledge,” said Teresa Nieves-Chinchilla, NASA deputy project scientist for the mission. Some of the first studies using Parker data have already published.

Solar Orbiter also has a seven-year mission and will come within 26 million miles of the sun. It will be able to brave the heat of the sun because it has a custom titanium heat shield coated in calcium phosphate so that it can endure temperatures up to 970 degrees Fahrenheit.

Although Parker Solar Probe will ultimately come closer to the sun than Solar Orbiter, it won’t be taking pictures of the sun within that range because the environment that close too the sun is extremely harsh, said Holly R. Gilbert, Solar Orbiter Project Scientist at NASA.

“Solar Orbiter is the limit of how close we can get with cameras,” Gilbert said.