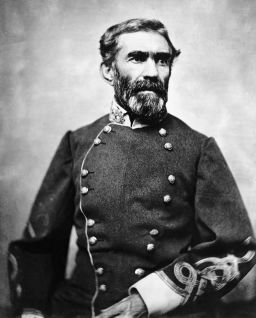

It’s head-scratching, really, that the most prominent Army base in America is named for Braxton Bragg.

He was on the wrong side of history, as a Confederate general and a slave owner.

It’s hard to find a redeeming account of Bragg. Historians repeatedly highlight just how poorly he got along with everyone – except perhaps Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States. Davis seemed to have a soft spot for Bragg, but he was still relieved of his command.

As it turns out, Bragg wasn’t even that good at his job.

The highlight of his military career was leading Confederate soldiers at the Battle of Chickamauga in Tennessee in 1863, perhaps the biggest and bloodiest win for the Confederacy on the western front of the Civil War – but it was a Pyrrhic victory.

Bragg failed to capitalize on the win and Union General Ulysses S. Grant ultimately overpowered his forces at the Battle of Chattanooga. That’s when Davis sacked him.

When Bragg later returned to the battlefield it was to lead a smaller contingent of forces in the loss of the last port of the Confederacy – a significant data point on the graph of the South’s defeat.

“The irony of training at bases named for those who took up arms against the United States, and for the right to enslave others, is inescapable to anyone paying attention,” retired four-star Army General David Petraeus wrote this week in The Atlantic.

Petraeus commanded coalition troops in Iraq during the surge and in Afghanistan.

Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina, is home to the elite 82nd Airborne – the military unit that can be anywhere within 18 hours, parachuting in behind enemy lines if needed. It’s also home to Army Special Forces and the training facility for Green Berets.

It’s a pretty important place. But when military-connected people talk about Fort Bragg, they don’t think too much about the man for whom it’s named.

This week, amid a sweeping national movement for racial equality, Marine leadership banned depictions of the Confederate flag from their installations. Not even on bumper stickers or coffee mugs. The Navy says it will follow suit.

The possibility of changing Fort Bragg’s name was also raised.

An aide to Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy revealed that his boss was open to a bipartisan discussion to rename the base and the nine other US military installations named for Confederate commanders.

Trump blocks discussions on renaming “Fabled Military Installations”

But on Wednesday, President Donald Trump quashed the idea, saying they are “part of a Great American Heritage, and a history of Winning, Victory and Freedom.”

“The United States of America trained and deployed our HEROES on these Hallowed Grounds, and won two World Wars. Therefore, my Administration will not even consider the renaming of these Magnificent and Fabled Military Installations… …Our history as the Greatest Nation in the World will not be tampered with. Respect our Military!!”

In World War II, that military included approximately 1.25 million African American troops.

And up to 500,000 Hispanic Americans, according to a House resolution honoring them.

They were joined by 44,000 Native Americans, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Many of those soldiers also left these bases.

And the names of Confederate soldiers still haunt the soldiers of color who serve.

“A part of this is the Confederacy and the fact that these individuals not only fought violently to overthrow the United States government, but quite frankly, fought in favor of continuing the institution of slavery, which has had a direct impact on the lives and minds of black Americans,” said Bishop Garrison, a black West Point graduate who served two tours in Iraq and currently works as Human Rights First’s chief ambassador to the national security community.

“So it is almost like a microaggression,” Garrison added. “It affects you in a certain way when you realize that you keep having to go to Fort Bragg.”

As current and former top brass distance themselves from or criticize Trump, he seems eager to shore up support among rank and file service members who are disproportionately from southern states.

On Thursday, America’s top general apologized for appearing in Trump’s photo-op at a church near the White House last week, after the National Guard helped federal law enforcement forcibly remove peaceful protesters from outside the White House, using pepper balls and flash bangs.

In an extraordinary moment, speaking to future military leaders graduating from the National Defense University, Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called it a “mistake” and said his presence “created a perception of the military involved in domestic politics.”

Defense Secretary Mark Esper broke with Trump last week when he said he disagreed with invoking the Insurrection Act to bring active duty troops to control protests, a move for which the President mobilized troops. Ultimately Trump did not deploy them.

Former Defense Secretary and four-star Marine General James Mattis slammed President Trump as “the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people—does not even pretend to try.”

Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell told CNN’s Jake Tapper that Trump has not been an effective president and that he lies “all the time.”

Navy Admiral Mike Mullen, another former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has been more reticent than others to criticize the President but wrote that he was “sickened” by Trump’s church photo op.

Marine Corps General and former White House Chief of Staff John Kelly. Marine Corps Gen. John Allen. Air Force Gen. Richard Myers. Army Gen. and former Joint Chiefs Chairman Martin Dempsey. Former Defense Secretary William Perry. The list is long.

In the past, Trump has embraced “his generals” but right now there’s no love lost.

He’s confronting a dangerously low approval rating and playing to his base.

White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany said that even discussing the renaming of the installations was akin to desecrating the sacrifice of fallen soldiers.

“To suggest these forts are somehow inherently racist and their names need to be changed is a complete disrespect to the men and women, who the last bit of American land they saw before they went overseas and lost their lives were these forts,” she said.

That prompted a sharp dismissal from a former Army captain turned author, Matt Gallagher, whose books include Kaboom: Embracing the Suck in a Savage Little War, a memoir of his time serving in the Army in Iraq.

He tweeted in response:

“If any of my fallen friend’s last thoughts were of the f***king base they deployed from, I’ll eat Kevlar.”

Please send story ideas and feedback to [email protected]

CNN’s Catherine Valentine, Ryan Browne and Zachary Cohen contributed to this report.