The world lost 3.8 million hectares of tropical primary forest in 2019 – equivalent to a football pitch every six seconds – according to a new report published Tuesday.

The loss of tropical primary forest makes up about a third of the 11.9 million hectares of tree cover that was lost last year, reveals a report from Global Forest Watch (GFW).

Primary forests are described as “some of the densest, wildest and most ecologically significant forests” in the world and are particularly important for carbon storage and biodiversity.

The hardest hit areas were in South America, Africa and Southeast Asia, the report says.

The report, which uses data gathered by the University of Maryland, shows primary forest loss was 2.8% higher in 2019 than the previous year.

Experts are also concerned the coronavirus pandemic could increase deforestation rates.

GFW tracks land use, climate and biodiversity changes around the globe through its open-source data monitoring and mapping tool.

Analysis focused on primary forests, which “once they are lost… can take decades or even millennia to grow back,” according to a post on GFW’s website by World Research Institute’s Mikaela Weisse and Elizabeth Goldman.

The rate of primary forest loss has remained “stubbornly high for the last two decades despite efforts to halt deforestation,” says the report.

Primary forest loss was lower last year than its peak in 2016 and 2017, but the total loss in hectares is the third-highest since 2000.

This amount of primary forest loss is associated with the same annual carbon dioxide emissions as 400 million cars, according to the report.

The worst-hit countries

Brazil accounted for the largest loss of primary forest, with more than 1.3 million hectares lost in 2019.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has faced global criticism and condemnation for the deforestation occurring under his watch. He has also been accused of incentivizing the activity of illegal ranchers, miners and loggers.

Data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) shows the first trimester of 2020 saw a more than 50% increase in deforestation compared to last year.

Meanwhile, in terms of total tree cover loss, Bolivia had its worst year in 2019 with more than 80% more trees lost than any other year on record, the report says. This follows several regulatory changes in recent years designed to encourage agriculture, the report adds.

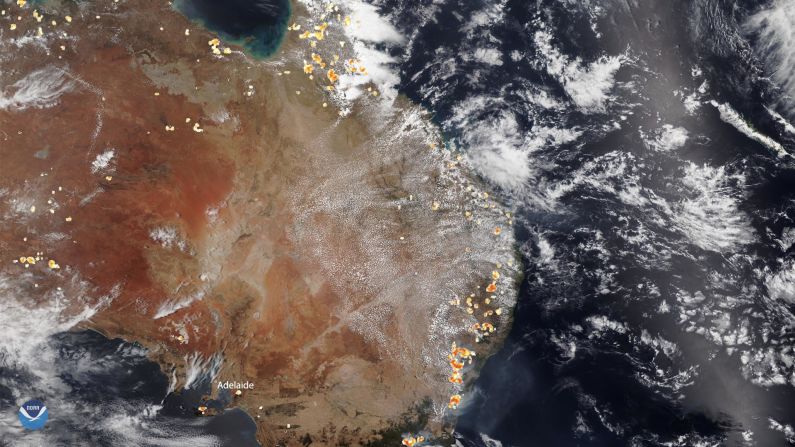

Widespread fires in Brazil, Bolivia, Indonesia and Australia impacted the rate of tree cover loss in 2019, though the analysis found that fires were both a “cause and a symptom” of tree loss.

According to fire data collected by the University of Maryland, 30% of fires in Brazil last year were in areas that had previously burned.

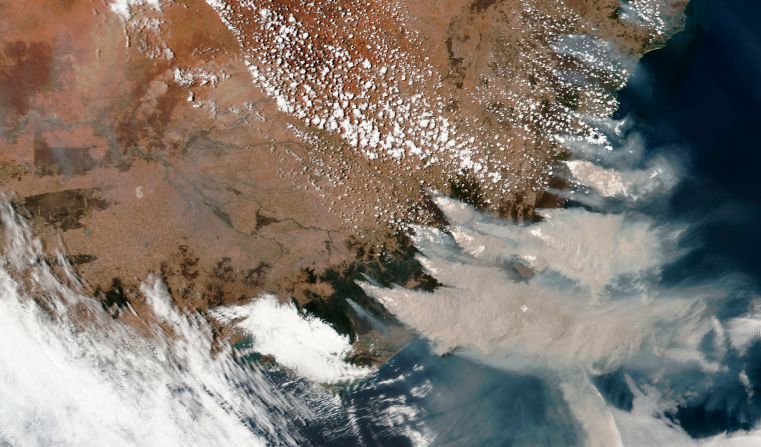

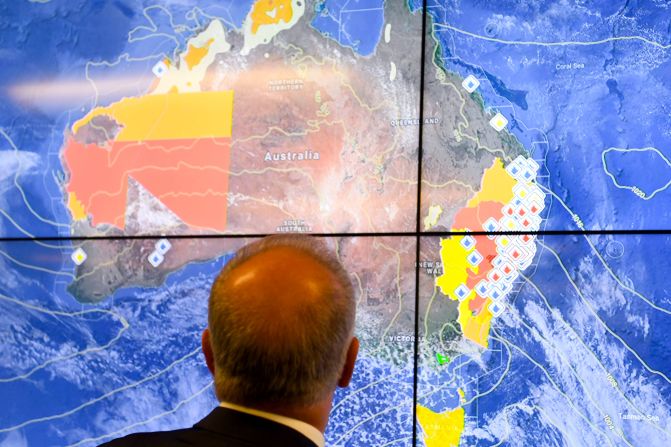

The report also hones in on Australia, which is not in the tropics but saw a record-breaking year for tree cover loss due to bushfires which captured the world’s attention in late 2019 and into 2020.

There was a six-fold increase in tree cover loss from 2018 to 2019, and the real extent of the damage is not yet known as some fires continued burning into 2020, according to the report.

‘Some promising downward trends’

West Africa showed some “promising downward trends” in 2019, according to GFW.

Both Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire reduced primary forest loss by more than 50% in 2019 compared to the previous year.

Although Indonesia is one of the areas with the highest amount of primary forest loss in 2019, it recorded its third year in a row of decline, the report says.

Colombia managed to cut such loss year-on-year after two years of significant increases. However, the report warns that a spate of deforestation alerts in the first part of 2020 may mean this progress is curtailed.

Some of the reasons for downward trends could be government actions and environmental policies, the report says.

The report comes a few months after it was revealed that the Amazon rainforest had lost the equivalent of 8.4 million soccer fields between 2010 and 2019 due to deforestation.

Coronavirus could pose further threat to forests

The pandemic will likely have an impact on deforestation, according to Weisse.

“While it’s too soon to quantify the impact of the pandemic on forests, we have been hearing anecdotally about illegal actors taking advantage of the situation to ramp up environmental crime, and also about the challenges that law enforcement agencies are facing during this time,” Weisse told CNN.

She added that researchers were concerned that governments might loosen environmental protections in the name of economic recovery.

Frances Seymour, who works with Weisse at the World Resources Institute, predicts that forests could be exploited further as people lose other sources of income.

“Temporary cash transfers and forest-friendly job creation are ways to reduce the need to rely on forests as a social safety net,” Seymour said. She also suggested making any corporate bailouts conditional on shifting to deforestation-free supply chains.