Before the pandemic, video games were a weekend-only activity in our house, allowed for one hour a day, Saturday and Sunday.

It was a compromise that worked for our family. My 7-year-old had a chance to dig in to his favorite games, and we parents felt like we were putting reasonable limits on an activity about which we were somewhat ambivalent.

But now he’s playing them daily — and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

In this lonely pandemic world, we still want our kids to get together to play, and they do, too. Unlike us boring grown-ups, they don’t get much out of chatting in group texts or through FaceTime (or even those work Zoom meetings).

They want to enter collective imagined spaces and discover the elastic possibilities that await. Only there, somewhere deep in the unreal, are they likely to start exploring, creating and, importantly, connecting.

Like most kids around the world, it’s been a long time since my son has been able to battle bad guys, travel to faraway lands or rescue animals with his friends in person. But, thanks to video games, all is not lost.

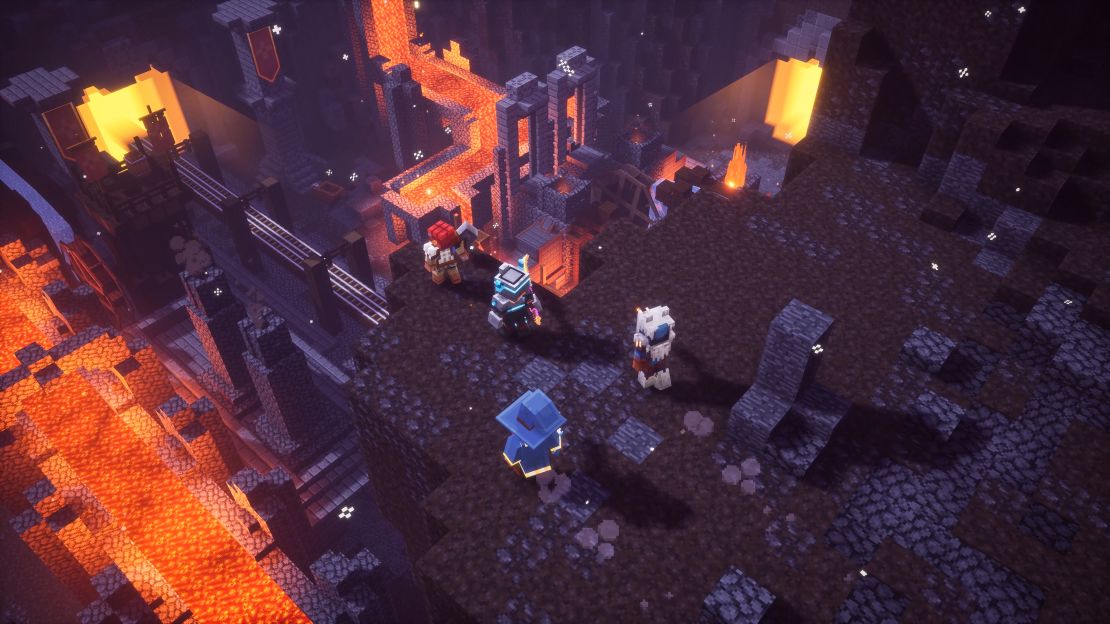

Nearly every day for an hour, he joins his friends online to explore, create and connect in video games like Minecraft and the nonviolent, more adorable Animal Crossing.

These aren’t the prescriptive, goal-oriented games from my youth, in which there were levels and a single objective (think 1980s-era Super Mario Brothers). Instead, they’re “sandbox” games, in which players have freedom to roam around extensive worlds, figuring out their own goals and finding their own way.

Yes, it’s virtual — not “real.” Still, these video games remain one of the only ways our kids can learn the kind of social and emotional lessons that they’re otherwise missing out on right now.

The pandemic is giving us a chance to see the benefits of video gaming. They’re significant and something — fear not, son — I won’t be forgetting when the world reopens.

The benefits of collaborative video gaming

“In spite of the stereotype of the socially awkward pale gamer, games are a good way to socially connect,” said Rachel Kowert, research psychologist and author of “A Parent’s Guide to Video Games: The Essential Guide to Understanding How Video Games Impact Your Child’s Physical, Social and Psychological Well-Being.”

“In this time of high anxiety and reduced social access … video games allow us to maintain friendship bonds in a multifaceted way,” she explained. “There’s collaboration and competition around a shared activity.”

Research has suggested that friendships — deep human connection — can be created and sustained through online play, Kowert said. Also, it’s fun, and fun matters for our overall well-being.

“As humans we have been playing since the beginning of time. This is an extension of that, through technology,” she said.

My son recently told me that the most fun thing he gets to do these days is play video games with his friends. I could feel bad that he isn’t saying that about some unplugged activity, like, say, building a fort out of twigs he collected in the forest. Or, I could feel good that the relatively small sliver of socialization he still gets brings him great joy. I choose B.

Eduardo A. Caballero is the executive director of Camp EDMO which, among its other offerings, uses gaming to teach social and emotional learning. For the curriculum, the camp teamed up with the University of California, Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center to figure out how to best incorporate character building into gaming, and other STEM activities.

My son was recently enrolled in one of Camp EDMO’s Minecraft camps, where he learned to respect other people’s ideas, and stand up for himself when others weren’t respecting his ideas.

“If you didn’t build it, you can’t break it,” I overheard his instructor explaining to the group one afternoon, articulating an ethic that easily transfers to the world outside his laptop.

“We work with platforms that allow kids to be creative, to have a personality, to have feelings and they’re great tools for social and emotional learning” Caballero said. “We always ask ourselves: What are we going to try to teach besides technology? What are the lessons that are going to apply to everyday life?”

Caballero said he sees kids develop empathy for others, become more considerate of others and find ways to problem solve together.

There are a number of studies that conclude that video gaming can bring about more prosocial behaviors among children, especially for those who play collaborative games. One found that gaming can lead to kids having more friends and being more willing to talk to others, and another found that gaming can make kids more inclined to help others. Also, researchers have found that children who were socially engaged while playing video games were more likely to be civically engaged as adults.

Jordan Shapiro, author of “The New Childhood: Raising Kids to Thrive in a Connected World,” poured through much of this research on whether kids can learn social and emotional skills through video gaming for his book.

While he’s not satisfied with the quality of most of the studies on the subject, he said he “couldn’t find a single good reason why” the socializing that takes place in video games wouldn’t either compliment or influence the socializing that takes place outside them.

While sheltering in place, Shapiro said video games are serving as his tween children’s very important “transitional space,” which gives them an opportunity to explore their identities without their parents around.

Identity formation is a big part of growing up, and, as research has suggested, can take place in the virtual realm. Games give children a chance to try on different avatars, personalities and even genders, with less severe consequences than the real world.

“Right now the only space to do that is digital,” he said. “Kids need that. They need that kind of socialization, even if you think it can be bad [online] or even if you think it can be better.”

Shapiro said another benefit to kids finding ways to engage online right now is that they will improve their ability to communicate through a computer. These are skills that will benefit them post-pandemic and far into the future.

Comparing a kid with little exposure to technology and his kids right now, Shapiro said his “kids have the capacity to socialize and read social cues online,” explaining that there are unique social skills for digital engagement that are best learned through spending time online.

“Without any practice with social coding online, you’re at a disadvantage.”

All video games aren’t created equal

Will every kid benefit from every video game? Of course not. Games like Little Big Planet 3 emphasize collaboration, Mario Kart encourages competition and Minecraft, which has a lot of cooperative possibilities, also allows players to slay zombies with a sword. (Never heard of any of these? Common Sense Media has extensive reviews of video games and breaks them down by age.)

Some games aren’t age-appropriate and some will be more interesting to some children than others. Researchers haven’t been able to find a clear relationship between playful aggression in video games and aggression in real life. But, like with everything else, children respond differently to different activities, and only a parent can decide whether or not that activity or particular game is beneficial for his or her child.

Still, there are ways to try to make online gaming a more socially rich experience for your children.

Caballero said to think of it like a playdate.

“You have to check in on them and ask them questions: Did somebody do something nice? Did you learn something new? Who cooperated well today?” he said, adding that parents might create structure for the get-together. Maybe today they’re supposed to go fishing on Animal Crossing. Or perhaps ice skating on Bloxburg?

To emphasize communication, run a video chatting software while the kids are playing together, either through a split screen or two devices. Even if their eyes are locked on the game, they can hear each other’s directions and reactions and offer emotional support when something goes right or wrong.

I hear a lot of “That was so awesome, dude!” and similar elementary age-approved affirmations coming from my son when he plays video games with friends or cousins.

If your child has never played a particular game before, it might be best to get them familiar with the game first, before they jump in with their friends. Kowert suggests watching videos online of people playing the games before starting them.

Also, Shapiro suggested matching your child up with someone who is also exploring the game for the first time, so they don’t feel left out or unskilled.

For all the parents out there who remain scared of video games and aren’t terribly fond of their kids spending more time online, one fix might be to get better acquainted with them.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

If your child has no experience, figure them out together. Or, if you’ve allowed them but out of guilt, shame or lack of interest have previously stayed away, let your child take you on a tour. You’ll probably be impressed by their skills and will also get a better sense of how video gaming can meet their particular relationship needs.

Including, just maybe, their relationship with you.

Kaitlee Venable, an instructor and curriculum writer at Camp EDMO, predicted that any request by a parent to a child to learn a video game will be met with an enthusiastic yes.

“I can’t imagine any kiddo who would not get excited about showing their parents how to play. They are going to be so excited,” she said.

Elissa Strauss is a regular contributor to CNN, where she writes about the politics and culture of parenthood. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, Glamour, Parents and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter @elissaavery.