Hundreds of fossilized human footprints made between 5,760 and 19,100 years ago have been discovered in Africa, shedding light on what life was like in ancient communities, according to a new study. This represents the largest collection of fossilized footprints found in Africa to date.

Researchers believed the 408 footprints, which form 17 different tracks, belonged to 14 adult females, two adult males and one juvenile male.

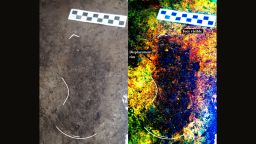

“The footprints were made in a volcanic mudflow, and when that wet ash dried it hardened almost like concrete,” said Kevin Hatala, study author and assistant professor of biology at Chatham University in Pennsylvania, in an email to CNN. “So the footprint surface itself is very resilient. But this surface was also buried by other layers of sediments, which helped to form protective layers that shielded the surface from the elements for thousands of years.”

The study published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

The footprints are located at the Engare Sero site, just south of Lake Natron, in northern Tanzania.

“It is notable that the site, which preserves the most abundant assemblage of hominin footprints currently known from Africa, is within roughly 100 km [62 miles] of the site of Laetoli, which preserves the earliest confidently attributed hominin footprints,” the authors wrote in the study.

The site was discovered by members of the local Maasai community, and they shared this information with conservationists in 2008. About 56 human footprints were visible at the site in 2009 when the research team arrived thanks to natural erosion. Excavations between 2009 and 2012 uncovered the rest. The 17 tracks were all made moving at the same walking speed in a southwesterly direction.

Clues to ancient human behaviors

Fossilized footprints are unique because they can preserve potential evidence of human behaviors and activities.

“Footprints preserve amazing windows to the past, through which we can directly observe snapshots of people moving across their landscapes at specific moments in time,” Hatala said. “They can inform us of how fast people were moving, in which direction they were heading, how large their feet were and sometimes whether the people who made them may have been traveling in groups. With such rich details, we can directly observe behaviors in the fossil record, something that is very difficult to do with other forms of data.”

In order to get a sense of the information contained within the footprints, Hatala and his colleagues studied the sizes, spacings and orientations of the footprints. Spacing and orientation can share the speed and direction of someone’s movement, while size can be used to estimate who made the footprints.

They were able to compare this data with that of footprints made by living humans to determine which footprints likely belonged to adults, juveniles, males and females, Hatala said.

“With these estimates, we were able to gain a detailed picture of who was traveling across this surface, how they were moving and whether or not they may have been traveling together,” he said.

This data was also compared with patterns of modern hunter-gatherer societies to understand the potential scenarios associated with these grouped footprints. And they realized that it was rare for large groups of adult females to travel together without adult males or children.

“One scenario in which this kind of group structure is observed is during cooperative foraging activities, in which several adult females forage together, perhaps accompanied by one or two adult males for some portion of that time,” Hatala said. “Infants may be carried, but young children who are old enough to walk will often stay behind rather than participate in the foraging activities.”

They believed that was the case here, with multiple women walking at the same speed and in the same direction as the two men and the younger man.

This suggests that labor was divided up based on gender in ancient human communities, with the women foraging while the men accompanied them. It’s similar to modern behavior by the Aché and Hadza hunter-gatherer societies in Paraguay and Tanzania, respectively.

Hatala and his colleagues regard the footprints as a “tantalizing snapshot,” offering windows into anatomy, locomotion and group behavior, which acts as a supplement to fossil data. Skeletal fossil data is also rare in this area, which makes the footprints even more intriguing.

They also found evidence of zebra, antelope and buffalo tracks 18 miles to the southwest.

“We know that these animals were living on the same landscape as the humans who produced footprints on the same surface,” he said.

There were an additional six tracks of footprints, moving at various walking and running speeds, in a northeasterly direction, but the researchers don’t believe they belonged to a single group traveling together.

“We hope that our study motivates future research that might help refine our abilities to use these amazing snapshots to reconstruct past behaviors,” Hatala said. “At Engare Sero, our focus has shifted to site conservation. Before we excavate any further, we want to work with the Tanzanian government to develop a long-term conservation plan, such that the site is still accessible for many generations to come.”