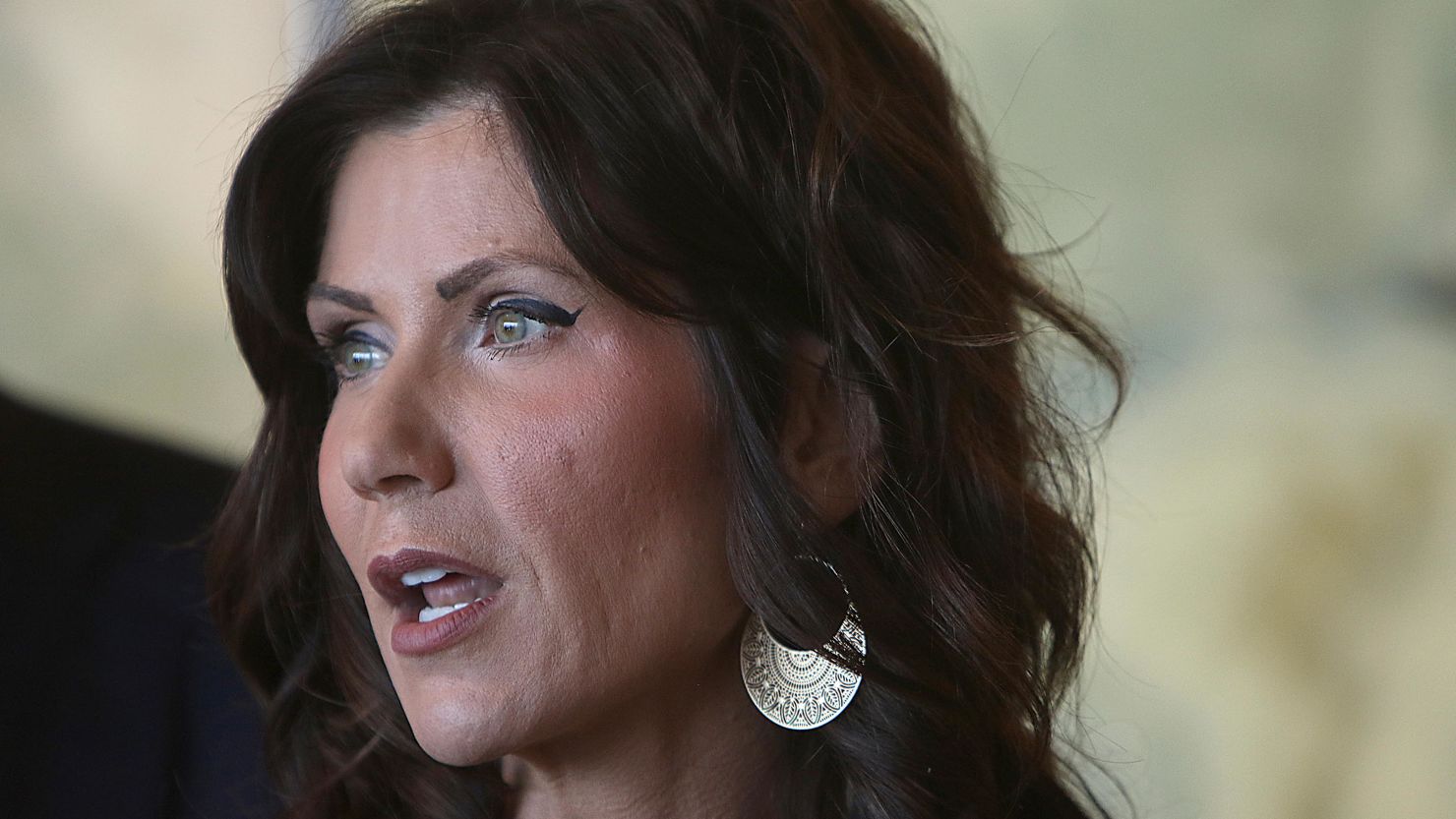

South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem’s standoff with the leaders of two Native American tribes over their coronavirus checkpoints is escalating as they battle over sovereignty and the governor’s ability to control restrictions on state and federal highways.

The Republican governor – who never enacted a stay-at-home order in her state despite a huge outbreak at a Sioux Falls meatpacking plant – threatened to sue the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and the Oglala Sioux Tribe in two letters Friday, arguing that their efforts to prevent the spread of the virus through roadway checkpoints was interfering with traffic. She ordered the tribes to dismantle them within 48 hours, a deadline which has now passed.

And on Monday, the president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe said in a news release that he will not remove checkpoints on roads within the reservation meant to stop transmission of the Covid-19 into the Pine Ridge Reservation as Noem has demanded.

“Since she won’t protect tribal health and safety, tribes have no choice but to take matters into their own hands,” said Julian Bear Runner, the tribe’s president, in the release.

The standoff is just the latest controversy that the 48-year-old former congresswoman has ignited in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. Hewing closely to the Trump administration’s philosophy that the nation’s top priority is reviving the economy while ensuring the continuity of the food supply chain, Noem denied requests from local officials to issue county-wide shelter-in-place orders near the Smithfield Foods meatpacking plant, which has now been linked tothe cases of more than 1,000 people, including employees and their contacts.

Like Trump, Noem also championed the unproven anti-malarial drug known as hydroxychloroquine, going so far as to announce that South Dakota would conduct the nation’s first statewide trial for the drug to test its effectiveness against the virus.

‘All we’re doing is trying to save people’s lives’

In this latest clash, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Chairman Harold Frazier told CNN’s Sara Sidner Sunday that he cannot understand Noem’s rationale for blocking checkpoints that are his tribe’s best tool to prevent the virus from infecting the 12,000 people who live on the reservation.

“All we’re doing is trying to save people’s lives,” Frazier said during an interview near one of the checkpoints Sunday. He noted that the tribe only has eight hospital beds and that the closest hospital with an intensive care unit is three hours away.

“All we have is prevention,” he said. “Because if we ever get the virus spread throughout our reservation, we don’t have the resources, the medical resources, to try to address it.”

Nationally, the virus has devastated some Native American communities, in part because of the scarcity of medical personnel and resources on their lands. The leaders of both the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe and the Oglala Sioux Tribe have maintained strict stay-at-home orders and curfews, while Noem recently told Fox News that South Dakota is “on the way back to normal.”

In a Facebook Live Saturday, Oglala Sioux Tribe President Julian Bear Runner described Noem’s checkpoint ultimatum as a “threat the sovereign interest of the Oglala people” that does not reflect the will of the people of South Dakota.

“Gov. Noem miscalculates our level of dedication to protect our most vulnerable people from crony capitalism thrust to force us to open our economy as they chose to do,” Bear Runner said. “There is no way to place a value on what we have to lose if we let them insult us this way… Right now, they are trying to divide us, as they always have.”

In her Friday letters, Noem argued the tribes must “immediately cease interfering or regulating traffic”on US and State Highways and remove all travel checkpoints.”

She argued that the tribal checkpoints do not comply with an April 8 memo from the US Department of the Interior that directs Native American tribes to consult and coordinate with state, federal officials or private landowners to reach agreement on temporary closures or restrictions on non-tribal roads.

Maggie Seidel, Noem’s senior adviser and policy director, stressed in a Sunday memo to reporters that “tribes are well within their rights to manage the flow of traffic on tribal roads, and the state has no objection to that.”

“The key here is that tribes are letting tribal members come and go as they please – the same is not true for non-tribal members,” Seidel said, an assertion disputed by the tribes.

Noem’s belief in individual responsibility and her reluctance to enforce strong statewide restrictions to fight Covid-19 has created friction with local officials throughout the course of the pandemic in South Dakota.

The rural state of nearly 900,000 people had 3,614 total positive cases and 34 deaths as of Monday afternoon. Of the 24,578 people tested in the state, about 15% have tested positive, according to state data.

The vast majority of coronavirus cases have been in Minnehaha County, where the Smithfield Foods plant in Sioux Falls is located. The plant, which employs 3,700 workers, shut down on April 12. In a press conference two days later, Noem called the decision to shut the plant down “a pause” – while acknowledging that more than half of the state’s positive cases at that time were either plant employees or their contacts.

In subsequent appearances, she emphasized the importance of getting the plant back online as quickly as possible to ensure the continuity of the nation’s food supply.

The plant reopened Thursday, with federal officials overseeing operations under the Defense Product Act. The state conducted a mass testing event last week for employees and their families. Noem has said it could be back at “full production” sometime this week.

Grounded in agriculture

While representing South Dakota in Congress for four terms before she was elected governor in 2018, Noem spoke of food supply as a national security issue, arguing that she didn’t want another country “to produce our food for us because then they control us.”

She was grounded in farming and agriculture from an early age, helping her family raise cattle and grow corn, wheat and soybeans on their farm and ranch. Her father died after falling into a grain bin in 1994 while trying to unclog a feeder line.

The accident led Noem to leave college and return home to help manage the family farm. The family’s struggle paying the estate tax after her father’s death shaped her interest in politics. (Speaking from that perspective in Congress, she was a forceful adversary for Democrats who argued that abolishing the estate tax was merely a giveaway to the wealthy).

Noem and her husband Bryon – who she has referred to as another “farm kid” from Hamlin County – operated a farm and ranch, as well as a hunting lodge and a family restaurant. She often says her greatest accomplishment is “raising three children who love the Lord, love their family, and know how to work hard,” according to her governor bio page.

She was elected to the South Dakota statehouse in 2006, where she rose to become assistant majority leader. She later won a seat in the and then to House of Representatives in 2010. In Congress, she sometimes went her own way, differing with the Trump campaign and administration officials, for example, on trade issues – advocating for agreements that expanded export opportunities for farmers. She also collaborated with Democrats to help expand access to health care in rural areas.

Throughout the coronavirus crisis, she has stressed the importance of tailoring the response to the needs of South Dakotans, repeatedly pointing out that the Mount Rushmore State is very different from East Coast states where the outbreak has hit the hardest.

“South Dakota is not like New York or New Jersey, so our solutions will look different than theirs,” Noem said in a Facebook post last week. “My job is to do what’s best for South Dakota, to protect public health, while also considering mental health and the economic consequences of my decisions.”