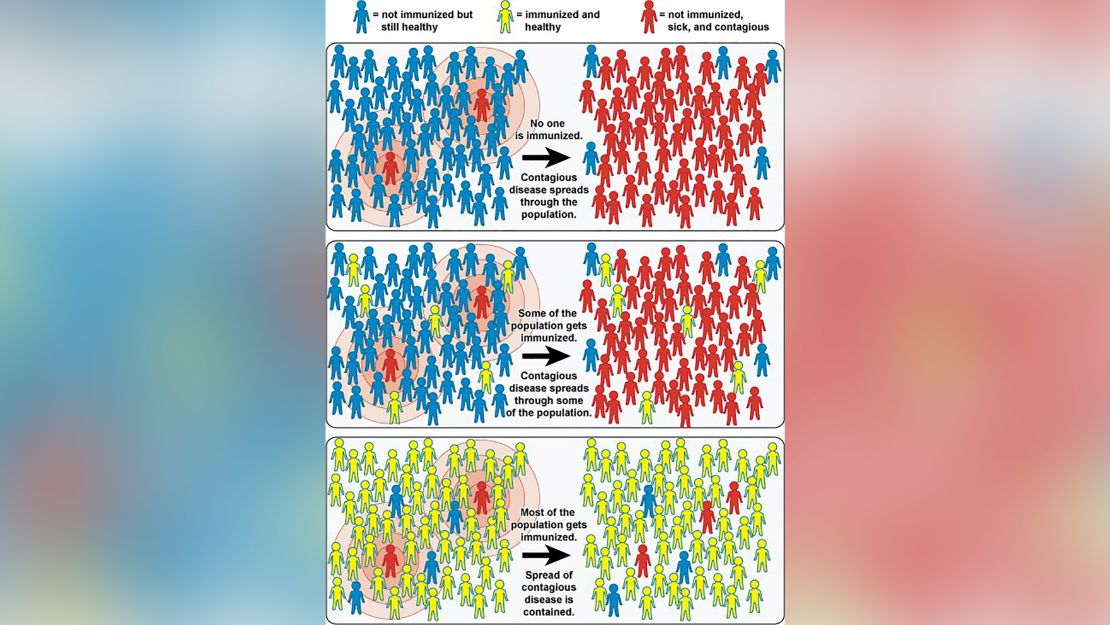

The concept of herd immunity is a simple one. But achieving it? Not so much.

As the coronavirus pandemic spread throughout the world, doctors, scientists, and government leaders alike have said that once herd immunity was achieved, the spread of the virus would be less of a threat. Herd immunity is reached when the majority of a given population – 70 to 90% – becomes immune to an infectious disease, either because they have become infected and recovered, or through vaccination. When that happens, the disease is less likely to spread to people who aren’t immune, because there just aren’t enough infectious carriers to reach them.

There are just two ways to get there: widespread vaccination, which for Covid-19 is still many months away, or widespread infections that lead to immunity.

Herd immunity by infection is not without risks

Most doctors and experts agree that allowing Covid-19 to just plow through populations might help reach herd immunity more quickly, but that would also overwhelm hospitals. More people would die, not just from coronavirus but from other infections, too. That’s why we’re all stuck at home – we’re flattening the curve.

“The advantage of stretching out the number of cases is that we will not exceed the capacity of hospitals to care for those who are particularly sick,” Dr. H. Cody Meissner, chief of pediatric infectious disease at Tufts University Medical School, told CNN’s Michael Smerconish in March.

And then there’s the issue that we don’t really know how immunity works with this virus.

Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the World Health Organization (WHO), said it’s not known whether people who have been exposed to the virus become completely immune to it and if so, for how long. That’s why governments should wait for a vaccine, she said.

The WHO has “seen some preliminary results, some preliminary studies, pre-published results, where some people will develop an immune response,” Van Kerkhove said. “We don’t know if that actually confers immunity, which means that they’re totally protected.”

A vaccine is a better answer, she added. “I mean, recently we had more than 130 developers, scientists, companies come together to say that they would be willing to work with us – to work globally to advance a vaccine. And that is something that we will push and the whole world is waiting for.”

And while, younger people are far less likely to die from Covid-19, they can still become sick enough to require hospitalization.

Even if catching Covid-19 once does make people immune to future infection, the US has not had enough cases to get close to widespread immunity.

“The level of people who’ve been infected, I don’t expect it would rise to the level to give what we call herd immunity protection,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN’s Jim Scuitto on Tuesday.

“What it will mean, it would protect those who have been exposed, but at the community level there would not have been enough infections to really have enough umbrella of herd immunity,” Fauci said.

As a vaccine has yet to be created for the novel coronavirus, some have argued that nations should forgo lockdowns entirely and try to achieve herd immunity by keeping the vulnerable indoors while allowing others to live out their normal lives – and get infected.

UK’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson seemed to support a similar belief back in March when he held off on banning large gatherings and closing schools.

However, Johnson later issued a nationwide stay-at-home order, effectively closing all nonessential businesses and banning public gatherings. He then contracted the virus himself, and spent three nights in the ICU. He has since been discharged from the hospital.

Why Sweden refuses to lock down

While much of Europe has gone into lockdown, one country has bucked the trend: Sweden.

Restaurants, schools and playgrounds in the Scandinavian country are open. Sweden’s Foreign Minister Ann Linde has said it’s not following the herd immunity theory, but rather relying on its citizens to voluntarily be responsible to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

But Sweden’s state epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, claimed herd immunity could be reached in the nation’s capital, Stockholm, within weeks.

“In major parts of Sweden, around Stockholm, we have reached a plateau (in new cases) and we’re already seein the effect of herd immunity and in a few weeks’ time we’ll see even more of the effects of that,” Tegnell said in an interview with CNBC.

The strategy hasn’t come without costs.

WHO has said it’s “imperative” that Sweden take stronger measures to control the spread of the virus.

Compared to other European nations that haven taken stricter measures, Sweden’s “curve” – the rate of infections and deaths caused by the coronavirus – is steeper. As of Wednesday, Sweden has at least 1,937 reported coronavirus-related deaths, compared to Norway’s 185 and Finland’s 149 deaths, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.

The push for antibody testing

It’s hard to tell where the US currently stands without widespread testing. That’s why so many people are pushing for antibody tests.

With a prick of a finger, the tests, which aim to detect if you’ve contracted the coronavirus, can help public health officials determine what portion of the population has been infected and, in theory anyway, has at least some immunity to the virus, said Caroline Buckee, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

One town in California has already started antibody testing on its residents. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said his state, which is the hardest hit in the US, would start large-scale antibody testing over the next week.

“This will be the first true snapshot of what we’re dealing with,” Cuomo said.

But scientists and physicians are skeptical about the reliability of the dozens of tests that have hit the market because many have not been reviewed by the FDA.

Plus, even approved tests are never 100% accurate.

The FDA has also warned that the tests could lead to false negatives because antibodies may not be detectable early in infection.

CNN’s Tim Lister, Sebastian Shukla, Nina dos Santos, Paula Hancocks, Yoonjung Seo, Julia Hollingsworth, Mallory Simon, Gina Yu, Curt Devine, Drew Griffin, Nelli Black, Scott Bronstein, Kristina Sgueglia, Augie Martin, Sanjay Gupta contributed to this report.