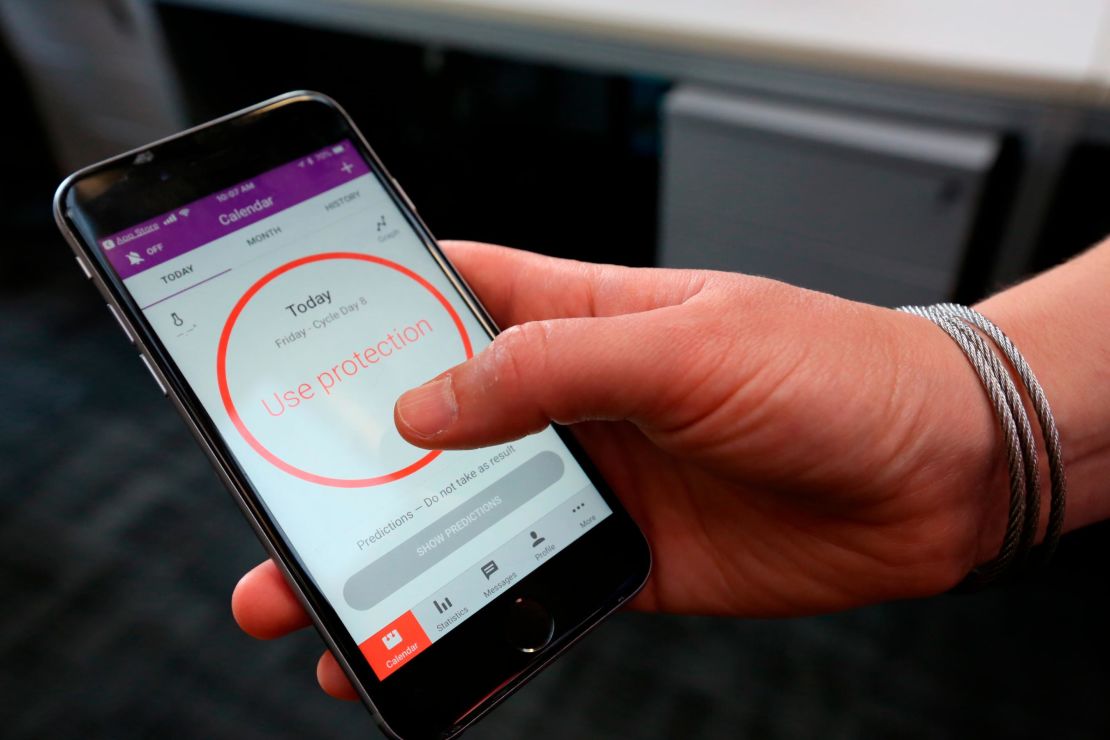

Smartphone period trackers or fertility apps are a daily part of many women’s lives as a tool to monitor their menstrual cycle or help them plan or prevent pregnancy. Such apps were downloaded at least 200 million times in 2016 alone.

But experts say women shouldn’t turn to fertility apps during the Covid-10 pandemic to avoid unintended pregnancies simply because people may be unable or too wary to visit their doctor face to face.

A new review is raising a red flag on the strength of the evidence on the effectiveness of the popular apps, saying research that does exist suggests they’re not always accurate.

“There is a lack of critical debate and engagement in the development, evaluation, usage and regulation of fertility and menstruation apps,” said the authors of the review, which examined 18 studies from 13 countries. It published Monday in the journal BMJ Sexual and Reproductive Health.

Caution

Women may turn to fertility apps during the coronavirus epidemic as a way to avoid consultations with overworked medical practitioners, warned Dr Diana Mansour, the vice president of clinical quality at the UK’s Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare of Royal Collegeof Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. (FSRH).

“We still don’t know how well many of these apps work to prevent unplanned pregnancies. All require correct and consistent use with daily inputting of data. Fertility awareness apps have the potential to broaden contraception choice, but at present, it’s important to treat fertility apps for contraceptive purposes with caution,” said Mansour, who was not involved in the research.

She urged women to speak to their physician by phone.

Keeping track of the menstrual cycle was the most common reason for using a fertility app, according to the review. Other reasons include using them to help conceive a baby, to inform fertility treatment or as a method of contraception.

Existing apps don’t necessarily involve women in their design or development and a woman’s motivation for using an app changes over time, the study said, but this wasn’t necessarily taken into account.

“This is especially important because the user is considered to be the single greatest ‘risk factor’ in the accuracy of apps, and this is particularly significant if women are seeking to prevent, or plan, a pregnancy,” the authors wrote.

The authors described their research as a “scoping review” that aims to provide an overview of the evidence, but unlike a systematic review, it doesn’t exclude research on the grounds of poor quality or potential bias because of the involvement of commercial interests.

‘Misleading’

When it came to getting pregnant, the research said that an app’s most important feature was to “accurately predict the fertile window,” but the authors said the limited evidence that did exist cast doubt on this function.

“The evidence seems to indicate that many of the most popular apps are not accurate, even though they might contain information that supports pregnancy planning or are marketed specifically for this purpose,” the authors wrote.

“[This] could be very misleading for women and couples that are trying for a baby.”

Several of the studies reviewed by the authors indicated that fertility apps can be successfully used as a means of contraception, but not all of them have been designed to include this feature, putting women who use these apps as a contraceptive at risk of an unintended pregnancy.

“I would rely on an app as a contraceptive if it was certified for that use and (b) I was very familiar with fertility awareness based methods,” said Sarah Earle and an author of the paper and a director at the Health & Wellbeing Priority Research Area at the Open University’s Faculty of Wellbeing, Education & Language Studies.

“I would probably seek out support and advice from a fertility specialist first AND (c) my cycle history was regular and within certain prescribed limits. And ONLY then,” she said in an email.

Natural Cycles is one of the best known apps and was the first and only to win US Food and Drug Administration clearance to be marketed as a contraceptive.

The app uses an algorithm that includes factors like sperm survival rates, body temperature and menstrual cycles to predict a woman’s fertile days. To use the app, a woman must take her temperature with a basal body thermometer, which provides accurate data to the 10th of a degree, every morning. A red light then warns if there is a risk of pregnancy and to use contraception; a green light says it’s safe to have unprotected sex.

Elina Berglund, co-founder and CEO of Natural Cycles, said that the paper brought to “attention to a reality that we have been aware of for years and that is that period trackers, fertility trackers, and digital birth control are not created equal.”

“As the first and only contraceptive app cleared by the FDA in the US and CE marked in Europe, our medical team has invested many resources into clinical studies that prove the effectiveness of our product,” she said.

“Other apps have not and while it hurts us as a company being lumped into a category of other apps that do not have the proper evidence, it also hurts women who may not understand the implications of downloading an app that will not work for her own personal needs.”

However, it has been dogged by controversy after more than three dozen users in Sweden experienced unplanned pregnancies, although the Swedish Medical Products Agency concluded after an investigation that no action was required. The company has also been criticized over its marketing strategy that uses social media influencers.

As for the unplanned pregnancies, the company said at the time those numbers “not surprising given the popularity of the app and [are] in line with our efficacy rates.”

The study called for more research on the field and greater involvement of fertility specialists and other health professionals.