India’s normally bustling streets are quiet. Delivery drivers wear gloves and face masks. Even the country’s unrelenting construction has come to a halt.

It’s all part of India’s unprecedented 21-day bid to stop the coronavirus pandemic in its tracks with a nationwide lockdown.

India is the world’s second-most populous country and has the fifth-biggest economy, with trade connections all over the world. Yet despite its size, the country of 1.34 billion appears to have avoided the full hit of the pandemic. To date, India has only 492 confirmed cases of coronavirus and nine deaths. By contrast, South Korea – which has a population only 3.8% the size of India’s – has more than 9,000 cases.

China, where the outbreak was first identified, has more than 81,000 confirmed cases in a population of 1.39 billion.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has maintained there is no sign of community spread, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has praised India’s swift response, which has included grounding domestic and international commercial flights and suspending all tourist visas.

On Tuesday night, Modi ordered a 21-day nationwide lockdown starting at midnight Wednesday. The order, the largest of its type yet to be issued globally, means all Indians must stay at home and all nonessential services such as public transport, malls and market will be shut down.

But fears are growing that the country remains susceptible to a wider, potentially more damaging outbreak. Experts have cautioned that India is not testing enough people to know the true extent of the issue – and have questioned the viability and sustainability of a nationwide lockdown.

In an interview with CNN last week, the WHO’s chief scientist Soumya Swaminathan said India had taken all the necessary steps to prepare for the virus, and had been communicating well with the public.

“Having said that, of course, we always have to prepare for a worse outcome,” Swaminathan said. “It’s better to be overprepared and to be overcautious than to be caught off guard.”

How bad is the outbreak in India?

So far, India has confirmed relatively few cases – but the country is also testing relatively few people.

In total, 15,000 tests have been conducted, compared with South Korea, where well over 300,000 people out of its 52 million population have been tested.

O.C. Abraham, a professor of medicine at Christian Medical College in Vellore in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, said that India should test extensively, just as South Korea did.

“The only way you can control a disease like this is that you test early and you quarantine them,” he said.

But Balram Bhargava, director-general of the Indian Council of Medical Research, said there is no need for “indiscriminate testing.” At a news briefing on Sunday, he said the country has a test capacity of 60,000 to 70,000 per week. By comparison, the United Kingdom –a country with 5% of the population size of India– says it is hoping to increase its test capacity to 25,000 a day.

Although the numbers are comparatively small, Modi has cautioned against being complacent, and said the assumption that the disease will not impact India is incorrect.

Like other countries, many of India’s confirmed cases have been connected to overseas travelers. The first six cases in the northwestern state of Rajasthan, for instance, were all contacts of the first case reported in New Delhi, who had a travel history to Italy.

Overseas, these sorts of clusters often spread into the local community, leading to a wider outbreak.

According to Bellur Prabhakar, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Illinois, there are a few reasons why the number of confirmed cases in India do not match international trends.

It could be due to a lack of testing, said Prabhakar, noting that “ignorance is bliss.”

Another possible reason is that coronavirus may thrive in colder conditions, meaning that it might not spread so efficiently in India, where temperatures are often more than 30 degrees Celsius (96.8 degrees Farenheit).

We know that influenza thrives in cold and dry conditions, but we don’t yet know if coronavirus follows the same pattern. Experts have cautioned against drawing too many conclusions yet, pointing to the many unknowns that remain about the virus itself and its spread in recent months.

But if the spread of coronavirus isn’t impacted by temperatures, that could be a problem for India.

“Unless the virus goes away because of the heat … I cannot imagine what could happen in India,” Prabhakar said.

Why an outbreak could be hard to control

Although it’s not yet clear why India’s case numbers are relatively low, as with other countries, it’s clear that an outbreak would be incredibly difficult to control.

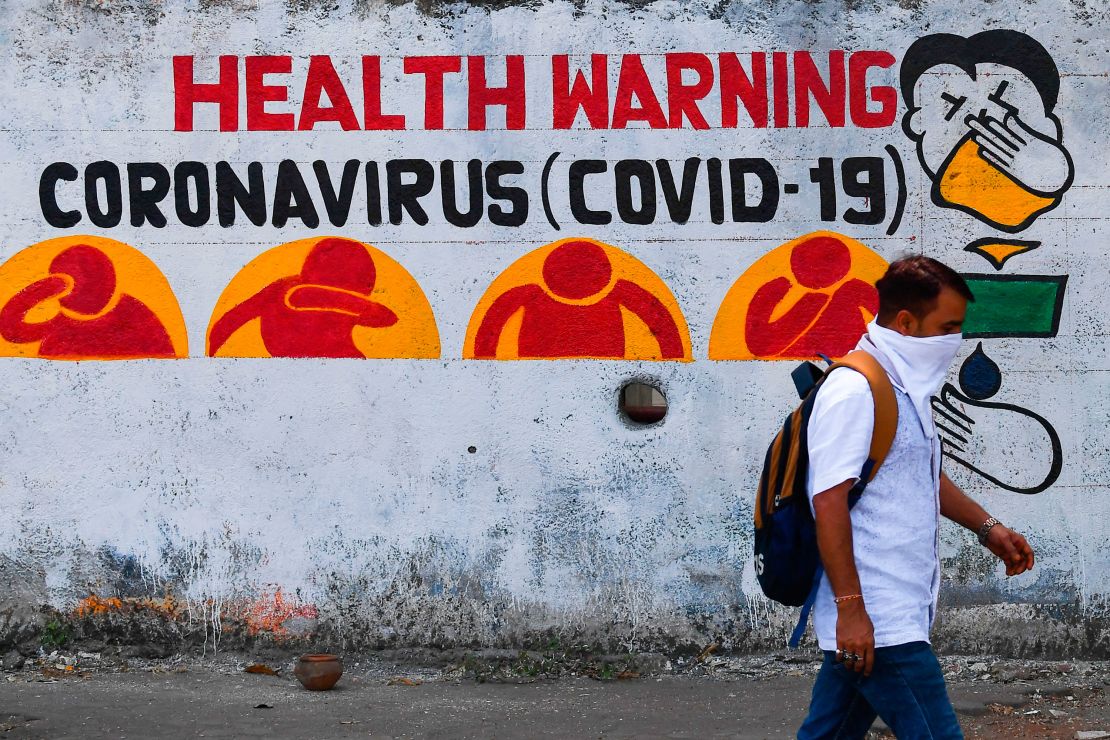

A growing number of governments are encouraging citizens to self-isolate, and wash their hands to control the spread of coronavirus. But in parts of India, even those basic measures would be extremely difficult.

In 2011, an Indian government report estimated that 29.4% of the country’s urban population live in low quality, semi-permanent structures, known as slums.

Many of the homes here don’t have bathrooms or running water. Some slum residents get their water from a communal tap, while others collect theirs in canisters and buckets from tankers that visit a few times a week.

This all makes it difficult to wash hands regularly. “Where on earth are they going to find the water and soap that they need?” questioned Prabhakar. “I think it’s going to be nearly impossible to implement that plan.”

It may also prove difficult to maintain the type of social isolation as ordered by Modi. In India, there are 455 people per square kilometer (or 1,178 people per square mile), according to World Bank statistics – significantly more than the world average of 60 people, and much higher than China’s 148.

“Social distancing in a country like India is going to be very, very challenging,” Prabhakar said. “We might be able to pull it off in urban areas, but in slums and areas of urban sprawl, I just don’t see how it can be done.”

Countries around the world have launched education campaigns advising people to sneeze into their elbow and avoid touching their face. But sharing that information with a population as large as India’s will also be a challenge, he said.

The challenge of going into lockdown

Every country that goes into lockdown faces a huge economic impact. But in India, telling people to stay home puts millions of jobs at risk.

According to official statistics from 2011-2012 – the most recent data available – there were around 400 million people in India’s labor market. Of those, more than half were self-employed, and 121 million were casual workers, meaning they had irregular work and were only paid for the days they worked.

Those people – India’s cleaners, household workers, and construction workers – are exactly the people who could be hurt by lockdowns.

The Ministry of Labor and Employment has issued a notice to businesses, asking them not to terminate employees or cut salaries.

Modi has already expressed his concern for the millions of workers who rely on a daily wage. “In such a time of crisis, I request the business world and high income segments of society to as much as possible, look after the economic interests of all the people who provide them services,” he said.

“In the coming few days it is possible these people may not be able to come to office or your homes. In such a case, do treat them with empathy and humanity and not deduct their salaries. Always keep in mind that they too need to run their homes, protect their families from illness.”

Chief minister of northern Uttar Pradesh state Yogi Adityanath said that each of the 1.5 million daily wage laborers in his state will be given 1,000 rupees ($13) via direct transfer to help them meet their daily needs.

“That might end up saving lots of lives if the government has a program to basically issue a paycheck to all those daily workers and people who earn below a certain level of income,” Prabhakar said.

But even if the authorities are able to roll out financial help for daily wage workers, not everyone will benefit.

According to government estimates, there are around 102 million people – including 75 million children – who do not have an Aadhaar identity card, which is used to access key welfare and social services including food, electricity and gas subsidies. Most of these people are essentially undocumented – and are less likely to receive a government handout.

Other difficulties facing India

On top of all of these issues, India also has an overburdened and underprepared health system.

“The public health sector is woefully inadequate,” said Prabhakar, explaining that there is a lack of medical supplies and trained staff in India.

As the WHO’s Swaminathan said, the health system across India is quite variable.

“There are some states with very well-resourced, well-equipped health systems, and others which are weaker,” Swaminathan said. “So the focus really needs to be both in short term and the medium to long term on strengthening the health systems in those states where it is relatively weak and this would involve a number of different actions.”

According to Christian Medical College’s Abraham, there are only about 50 to 60 specialists in India who have received formal structured training in handling infectious diseases.

According to the World Bank, India spends about 3.66% of its GDP on health – far below the world average of 10%. Although the United Kingdom and the US have struggled to deal with their own outbreaks, each spend 9.8% and 17% of their GDP on health, respectively.

At a news conference on Monday, Lav Agarwal, a senior official with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, said the government is working with all of India’s states to increase the capacity of health facilities.

CNN’s Esha Mitra and Vedika Sud contributed reporting from New Delhi.