Editor’s Note: Merrill Brown, a journalist, educator, executive and consultant, is the founder and CEO of The News Project Inc., which provides technology and services for small- to medium-sized news organizations. He was founding editor-in-chief of MSNBC.com, a former reporter and executive at The Washington Post, and founding director of the School of Communication and Media at Montclair State University. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion at CNN.

It is hard to imagine any newsroom in America where in recent weeks the pressure is more intense than it has been in the newsroom of The Seattle Times. if you’re local reporter, a sports reporter, a features or entertainment writer, your beat focuses on or touches on coronavirus. Little else matters, it seems. That’s the mandate for the paper’s roughly 155-member newsroom, according to the paper’s executive editor Michele Matassa Flores.

I asked Matassa Flores how she and the organization juggle the priorities of a metropolitan daily in a metropolitan area of 4 million people. “The story is so big in Seattle and in the region that there’s isn’t a lot else. Sometimes on other big stories you have to make hard choices but there’s no need to convince anybody right now. Our sports reporters are focused on contingency plans. Everybody is.”

That’s because Seattle has been considered the coronavirus epicenter as it is the home of 642 of the nation’s virus cases, about a quarter of the nation’s total, and 40 of the 60 deaths, as of March 14.The community is a ghost town, a boomtown now paralyzed and struggling to keep up with both the health crisis and the information challenge.

There’s only one other type of story that a newspaper would be covering that’s akin to the experience faced today by those working at The Seattle Times covering the coronavirus.That’s war. And the closest experience Matassa Flores can imagine in the paper’s history is the internment of 7,000 members of the Japanese community in Seattle early during World War II.

“In our newsroom, the biggest thing that’s surreal is that our lives as Seattleites and everything about Seattle is surreal,” she says. “There’s no one out on the streets. The city feels completely different. In the newsroom, usually when there’s a big story to cover we team up and cover it. In this case we’re all affected by it.”

While the local news world is in turmoil, the Seattle Times is reminding its community and people worried about the future of news why it matters so much. “People seem really grateful for what we’re doing,” Matassa Flores says. “We are extremely fortunate to work for a family owned independent paper.”

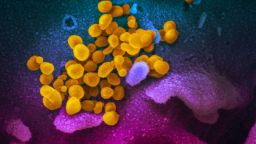

They’re offering factsheets, a “visual guide” to the virus, a school closing tracker, constant updates, rich graphics, opinion columns – a stunning display of the capabilities of a local news company when its community needs it more than ever. “People seem grateful for what we’re doing,” Matassa Flores says modestly. “People would not be getting the information they need from anywhere else if we didn’t have the size staff we do.”

The controlling owner is Frank Blethen whose family has had the paper for four generations. It is one of the highest-profile major newspapers in the country that’s still independent and locally owned. The Times touts two breaking news Pulitzer Prizes over the past decade. Blethen has for many years been an outspoken crusader for policies that can keep independent newspapers afloat. While The Seattle Times hangs on, it still is facing the possibility of further cuts to a news operation that according to Matassa Flores was twice as big as it is now at the dawn of the century.

Blethen writes, speaks out and lobbies for newspaper interests and has long been a critic of newspaper chains and the massive consolidation that has taken place in the industry over the past 30 years. On Dec. 20, before coronavirus crippled Seattle, Blethen ripped into the bankers and investors consolidating ownership of many of the nation’s largest newspapers, and inevitably shrinking payrolls.

“This is a system literally on life support as it suffers through the final stages of disinvestment and destruction by a handful of non-democratic fiscal oligarchies (hedge funds and distressed-asset players) who control most of the country’s newspapers,” he wrote in the Times. He has convened leaders to build support for what he is proposing, the establishment of a Save the Free Press Initiative with a number of goals including changing the financial and strategic dynamics that face newsrooms and news organization owners, both print and internet.

He even managed to lead the charge to get legislation signed into law in December called the Save the Community Newspaper Act. It allows at least a dozen papers to defer pension payments required by employee pension funds. According to Blethen, as reported by his paper, the Times would “have been threatened with bankruptcy within a year or two” without the relief.

The national spotlight focused on The Seattle Times might aid its chances for survival, although the likely downturn from the coronavirus tragedy in Seattle’s economic fortunes can’t help. What does have real tangible meaning is the spotlight on the extraordinary value of a vital newspaper, hanging on in times of both community crisis and its own financial peril at a time when two thirds of the nation’s counties have no newspaper and a fifth of US newspapers have shut down, according to a University of North Carolina Hussman School of Journalism and Media study.

There are new nonprofit models emerging for newspapers in markets as big as Salt Lake City and Philadelphia and local news internet only sites are growing rapidly in some market although Blethen for one believes in helping save the for-profit alternative. (Disclosure: I am founder of a startup company that is working to provide services and technology to news organizations.) The Times had a firm “paywall” requiring subscription until February 29 when the first death was reported there and the paywall was lifted. Even so, Matassa Flores says there’s been a surge in subscriptions.

While Matassa Flores and her colleagues think about their daily challenges, around maintaining six feet distance from those they interview in person, photographing those who are quarantined from afar, trying to figure out what’s going on in hospitals that reporters can’t always actually observe while at the same time providing as much of what she calls “utilitarian” coverage as possible they are now doing everything but printing the paper from their home offices (they fully analyzed and upgraded the technology access of every staff member).

“We live the story we are covering,” she says. It is hard to imagine Seattle without this resource. Perhaps her newspaper’s work in informing the public and saving lives in Seattle will accelerate a slowly developing national conversation about news. It shouldn’t take tragedy to do so.