Editor’s Note: Elissa Strauss writes about the politics and culture of parenthood. The views expressed in this commentary are her own.

We live, for the most part, fairly similar lives to our next-door neighbors. Both households have two working parents, two kids and an appreciation for the way California weather affords them unscripted, outdoor play year-round.

We are all busier than we want to be, but our neighbors have an extra, unnecessary hurdle that makes life more difficult.

Next door, the kids have homework. This involves 30 minutes of child-wrangling and patience-testing five days a week, pressure-cooking the little downtime they have together as a family.

Meanwhile, our family takes that time to enjoy our kids. No efficiency, no productivity, no agenda; just parents and children hanging out.

There’s been a lot of research and debate on the academic value of homework for school-aged children. The results, although somewhat mixed, generally conclude that homework provides no advantage for kids in elementary grades. As children get older, the potential benefits of homework grow, but less than you probably think.

Missing from the homework conversation is how no-homework policies benefit the whole family – parents and caregivers included.

School schedules and cultures were created for a different time, when moms were expected to be available to children during non-school hours. But today, the majority of families have either dual-working or single parents. Reconfiguring the education system to adapt to this current reality is a big project. We need to accommodate for the fact that nobody’s home to watch kids after school and during holiday breaks, or to spend four hours building a “Bridge to Terabithia” diorama on a Thursday afternoon.

The remedy to this would likely involve an overhaul of our paid leave and vacation policies, as well as modifications to our daily and yearly school schedules. This is not a quick fix.

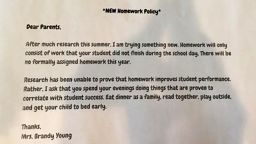

Ending homework for elementary school-aged kids is, on the other hand, relatively easy. We just have to stop doing it.

We need to do less

Feeling overwhelmed is a defining trait of today’s parents and caregivers. We have too much to do, our kids have too much to do, and leisure and happiness are the prices we pay for it.

One recent survey of 2,000 parents commissioned by Crayola Experience found that more than half of parents feel they are too busy to enjoy the fun of parenting. A similar number told Pew Research Center they struggle to balance the responsibilities of home with the responsibilities of a family. We feel guilty, and we feel tired. We lack the energy to make it through the week, let alone figure out how to get ourselves out of this mess.

When every minute is accounted for, sometimes two or three times over, a reprieve from something as seemingly minor as homework can make a big difference.

“The time families have together is really short; it is much shorter than what people would like. And when you are together everyone is fried,” said Brigid Schulte, author of “Overwhelmed: Work, Love, and Play When No One Has the Time” and director of the Better Life Lab. “If you are stressed and cranky, and your kid has been in aftercare too long, and then you get home and have to force them to do their homework, it removes the sense that home is a supportive, loving place where you can connect.”

Schulte encourages parents and caregivers to resist homework. This might include fighting for no-homework policies at their children’s schools, and pushing back against unrealistic homework assignments. Reach out to a teacher and tell them why a particular assignment is burdensome or causing unnecessary stress and, if this is the case, why your child won’t be able to meet the teacher’s expectations, she suggested.

“The most important thing is to look for small wins right now,” she said, referring to the battle against busyness. Gaining roughly 30 minutes a night, or two-plus hours a week, has the potential to make a dramatic difference in family well-being, giving us an opportunity to remember why exactly we had children in the first place.

Teach your children, and yourself, to do less

It can feel scary to slow down. Rising income inequality has turned parenting into a competitive sport. It’s a winner-takes-all world and we want our kids to be the winners — unhappy, stressed-out winners.

There is so much out there telling your children they need to do more and be more, and that whatever they think is enough is most definitely not enough. This means that parents and caregivers provide what is likely kids’ only shot at learning about leisure and togetherness. The overwhelming message from decades of research has found these are the main ingredients to happiness and well-being.

Getting rid of homework is a relatively simple way to combat this high-stakes problem. It gives parents and caregivers the opportunity to teach their children these essential – albeit systematically ignored and undervalued – skills.

“Kids should have a chance to just be kids and do things they enjoy, particularly after spending six hours a day in school,” said Alfie Kohn, author of “The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing.” “After all, we adults need time just to chill out; it’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.”

This isn’t to say that the downtime has to be mindless. Kohn suggests that parents and caregivers can, with their kids, cook, play board games, read or watch TV and then discuss what they read or watched. (Ideally, it’s something parents would enjoy as well.) All of these activities require logic or analytical skills, and can help uncover kids’ passions, as well as areas in which they might be struggling and need additional help.

These activities can also help kids build the kind of skills we associate with homework, said Josh Cline, a public school teacher in Oakland, California. Perseverance and stamina, for example, are required to sit through a story and then discuss it, to complete a batch of brownies or play a game of checkers or chess. “It’s better to grow those skills doing things kids find interesting than forcing them to slog through worksheets,” he said. That said, if worksheets are your kid’s thing, Cline said to give them a shot — as long as it is clear they have a choice.

From an academic standpoint, Cline’s main interest is for kids to be reading at home. However, he says, forcing it is likely to backfire. Instead, parents and caregivers should try to encourage reading by giving their kids plenty of choices, and, whenever possible, integrating reading into a cozy routine (that may or may not include hot chocolate).

But ultimately, the best replacement for homework is, simply, a parent or caregiver’s attention.

“Spend time with them and see them as people. At school, they operate as a herd, and as hard as I try as a teacher, I can’t give them all the attention they deserve,” Cline said. “At home they should be seen as the unique, individual, interesting and brilliant people they are.”