Hong Kong’s protest movement grabbed the world’s attention with million-strong rallies and city-stopping unrest. But it won big on the weekend by staying silent.

The landslide victory for pro-democracy candidates in Sunday’s district council elections is a stinging rebuke to the city’s government – and an example of what protesters can achieve given the opportunity.

By avoiding unrest and trusting voters to support them, protesters scored a bigger victory than if they had disrupted the polls. They also demonstrated that far from devolving into anarchy, as some on the government side have claimed, the protest movement can – unlike the police, Beijing or the city’s leaders – control when and where the unrest takes place.

Sunday saw beautiful blue skies, long queues and one of the calmest days in Hong Kong since the protests began in June. Far from the visions of destruction and anger that have dominated coverage recently, this was a city that worked. And judging by the results, it worked in spite of, not because of, its government.

According to public broadcaster RTHK, opposition candidates took nearly 90% of the seats up for grabs. Going into Sunday’s elections, all 18 district councils were controlled by pro-Beijing parties. As counting wrapped up Monday, all but one had flipped to overall pro-democratic control. The only outlier, the Islands council, includes a number of appointed members – even then, pro-democracy candidates took a majority of the elected seats.

In this, the elections were a demonstration of people power in more ways than one. Protesters showed they had the discipline to let people speak, and they were rewarded with a resounding vote of confidence. The question now is whether the government will listen.

Stunning results

District council elections should be boring. Only in a system like Hong Kong’s, where other avenues for democracy have been increasingly stifled, could they gain such outsized importance.

Sunday’s vote was framed as a de facto referendum on the protests by all sides. With turnout high from the moment polls opened – and overtaking the 2015 total by midday – many were predicting a win for pro-democracy candidates, but few expected the utter drubbing they delivered.

From the heart of the city’s financial district, to outlying islands and working-class estates in Kowloon, pro-democracy and anti-government candidates turfed out established pro-Beijing councilors.

Even the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), the city’s largest pro-Beijing party and possessor of one of the most effective get-out-the-vote operations, could not withstand the tide of anti-government feeling. Less than 20% of the party’s candidates were victorious — 21 out of 181 – and many leading figures, including vice-chairman Holden Chow, were turfed out of their seats.

Speaking to CNN ahead of the vote, Chow said he expected a defeat but that pro-establishment parties would bounce back. Asked why Hong Kongers should be allowed to vote for local representatives but not the city’s leader, he said “we want democracy which is pragmatic and fits Hong Kong’s situation, and would not ruin our relationship with the central government.”

Beyond just the symbolism of Sunday’s vote, control over a majority of district councils gives pro-democracy members the right to select 117 of the 1,200-member “broadly representative” committee that chooses the city’s leader. This means the opposition will have more of a say in who succeeds embattled current leader, Carrie Lam, in 2022.

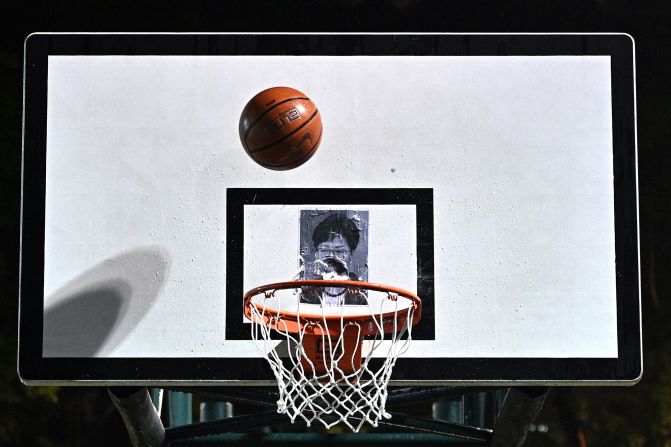

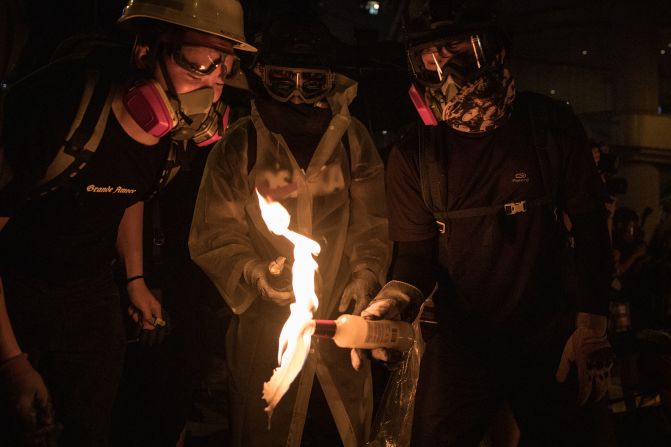

In pictures: Hong Kong unrest

Will the government listen?

With the elections wrapped up and the district councils transformed, the fight to frame the narrative will now begin.

On the government side, the scale of the losses for pro-Beijing candidates and the fact that many prominent establishment figures cast this as a referendum on the protests will make avoiding the blame difficult.

For months now, the government has refused to brook any political settlement, framing the protests as a law and order issue and putting the onus on the city’s beleaguered police force to bring them under control. The theory was that as protests became more disruptive and violent, they would alienate many moderates to the government’s benefit.

The supposed “silent majority” of anti-protest voters failed to show up on Sunday however. If anything, what was previously understated was the degree of anti-government feeling, not anti-protest sentiment. The pressure will now be on leader Lam to come up with some kind of new tactic or solution to the protesters’ “five demands,” or risk even larger protests from a reinvigorated movement.

Those five demands are: withdraw the extradition bill that kicked off the entire crisis (since achieved); launch an independent inquiry into allegations of police brutality; retract any categorization of a protest on June 12 as a “riot”; amnesty for arrested protesters; and introducing universal suffrage for how the Chief Executive and Legislative Council are elected.

Joseph Cheng, a professor of political science at the City University of Hong Kong, said the government needs to seriously consider the risk of failing to effectively respond to the elections – even if it remains unwilling to brook any compromise.

“There must be a process of reconciliation, a dialogue with the pro-democracy movement,” Cheng added. “But if no such responses are made in the near future, then the protesters will return to protests and clashes with police and so on.”

In a terse statement Monday, Lam said her government “respects the election results.”

“There are various analyses and interpretations in the community in relation to the results, and quite a few are of the view that the results reflect people’s dissatisfaction with the current situation and the deep-seated problems in society,” she added. “(The government) will listen to the opinions of members of the public humbly and seriously reflect.”

Moving forward

Protesters cannot afford to be too complacent about Sunday’s results. While they may seem a full-throated approval of the movement, it will likely be impossible to know whether people voted in favor of pro-democracy candidates or for the protests themselves, or simply to send a message to the government.

Sunday’s results also indicate some desire for reorienting the protests’ demands. While some victorious candidates did mention an inquiry into alleged police brutality – by far the chief demand since the extradition bill was officially withdrawn in September – the majority ran on a broader democracy plank, and it is this that connects all opposition voters, and even some in the pro-establishment camp.

Movement towards full universal suffrage has been stalled since 2014, when Beijing’s refusal to allow truly free elections for the city’s leader sparked the Umbrella Movement.

Of the five demands, the call to restart the political reform process has been the least emphasized – but it is also the only one which looks forward and seeks to achieve fundamental change. Even calls for investigating the police only look at past alleged crimes, not a way to change the makeup or behavior of the force in future.

The lack of trust in the city’s leader and legislature due to their undemocratic selection is at the root of the protests – Lam was not trusted to oversee extraditions, and elected lawmakers cannot exercise effective oversight of police – but convincing Beijing to allow any changes to this system is perhaps the most difficult of all the demands.

It has been pointed out many times that had Lam responded to the initial mass protests against the extradition bill, she might have avoided the entire crisis. Equally, had an independent inquiry been announced months ago when the bill was finally withdrawn, it might have ended there.

Now voters have shown not only the depths of the discontent, but also their power. And it may be the only thing that can truly satisfy them is overhauling the entire system.