Russia’s influence reaches deep into the British establishment and successive UK governments have turned a blind eye to it, lawmakers were warned, according to multiple sources familiar with testimony given to a parliamentary inquiry.

Members of the cross-party Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) were told that Moscow built up a network of friendly British diplomats, lawyers, parliamentarians and other influencers from across the political spectrum. One witness described the development as “potentially the most significant threat to the UK’s institutions and its ways of life,” according to testimony seen by CNN.

The committee’s unpublished final report into Russian meddling in UK politics, titled simply “Russia,” is at the center of a storm in the UK, where parliament was dissolved on Wednesday ahead of a general election in December. The committee’s chairman, Dominic Grieve, has accused Prime Minister Boris Johnson of sitting on the report and claimed Downing Street had given “bogus” explanations for not publishing it.

Opposition politicians have accused the government of a cover-up, saying it could raise awkward questions about the validity of the Brexit referendum in 2016 and expose the alleged Russian connections of some in the ruling Conservative party.

The ISC, which provides oversight of Britain’s intelligence and security agencies, and whose nine members are bound by the UK’s Official Secrets Act, completed its investigation in March. Its report was submitted to Downing Street for approval on October 17, after a lengthy period of clearance with the security services. Sources have told CNN the report includes a heavily redacted annex.

Grieve, a former attorney general who is no longer a member of the ruling Conservative party, told the House of Commons on Tuesday that it was usual practice for Downing Street to approve ISC publications within 10 days. The report may not now be published for months, he said, as ISC reports can only be released when parliament is sitting and the committee is constituted.

Downing Street has repeatedly denied that the failure to publish the report before the election was politically motivated. In Parliament this week, Foreign Office minister Christopher Pincher said it was routine for Downing Street to subject ISC reports to further checks before they were published, and that it would be released “in due course.” Downing Street declined to comment further to CNN.

Report under wraps

The contents of the ISC report, the product of an extensive investigation, have remained tightly under wraps. But CNN has been provided with written testimony from two of the committee’s witnesses, and has been briefed on oral testimony given by two others, all of whom warned that Russia had established deep ties to the UK political scene and that not enough had been done about it.

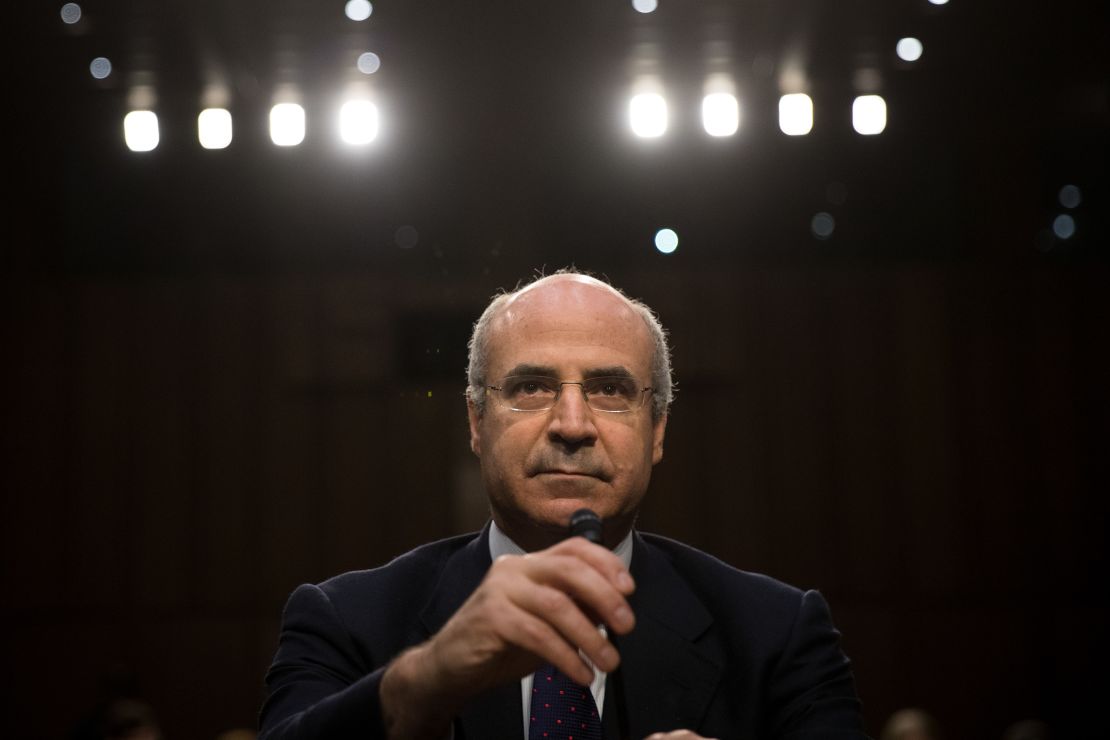

Among those invited to give evidence were Christopher Steele, the ex-British spy behind the Trump-Russia dossier and Bill Browder, founder and CEO of Hermitage Capital Management and a vocal critic of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Britain’s domestic and foreign intelligence agencies, MI5 and MI6, also fed into the committee’s inquiry, according to sources familiar with the material gathered.

During their investigations, lawmakers were told that successive British governments had downplayed the threat. One witness said “political considerations seemed to outweigh national security interests,” according to testimony reviewed by CNN.

Witnesses whose testimony CNN is familiar with told the committee that Russian agents were targeting research roles in the House of Commons, acquiring British citizenship to funnel cash to political parties and employing public relations firms to cleanse reputations.

Browder gave the committee a list of Dubai-based UK citizens who, he alleged, had acted on behalf of thousands of shell companies used to launder Russian cash linked to an organized crime network.

In written testimony submitted to the committee and seen by CNN, Browder alleges that Putin had used the proceeds of illegal asset seizures and money from corrupt sources to develop a “network” of well-connected, influential British figures, enabling the Kremlin “to infiltrate UK society and to conceal the underlying Russian controllers and their agendas.”

Unless tackled, such a network “will have serious detrimental effects on the UK democratic process, rule of law and integrity of the financial systems,” he warned.

In the statement, submitted in September 2018, he went on to say that “the Russian state effectively uses the Western persons… taking advantage of their identities, skills, expertise and contacts in the West to infiltrate Western societies,” to amass intelligence which is then used for the Kremlin’s propaganda purposes.

There is no suggestion in Browder’s testimony that British citizens broke the law, but the American-born financier recommended to the committee that lobbyists be required to register their work for foreign entities and law enforcement agencies are given more resources to crack down on money laundering.

CNN has approached the Kremlin for comment and will update this story if and when a statement is provided.

Moscow’s high-level links

Browder, who has described himself as “Putin’s No. 1 foreign enemy,” was once a supporter of the Russian president and the largest foreign investor in the country’s stock market. In 2005, five years after Putin was first elected president, Browder fled to London after being deemed a threat to Russian national security. He says his expulsion was due to his outspoken criticism of Russia’s corporate governance.

Browder campaigned forcefully for the Magnitsky Act, a US law that provides for sanctions to be imposed on Russian individuals. It’s named for Browder’s former lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, who died in suspicious circumstances in 2009.

In his written testimony to the ISC, Browder accuses well-connected figures of involvement in an effort to help Russians who wanted to avoid being targeted by European Union sanctions. According to Browder’s testimony, among those involved was Peter Goldsmith, who was attorney general in the Labour government of Tony Blair, and his firm Debevoise & Plimpton. That firm hired CTF Corporate and Financial Communications (CTFCFC), a public affairs outfit co-founded by Lynton Crosby, a polling expert who has worked on Conservative party election campaigns.

Debevoise said it could not comment on confidential client matters. In an emailed statement the firm, which said it was also speaking on behalf of Goldsmith, said: “Everyone is entitled to legal representation, and efforts to discourage lawyers from representing certain clients are irresponsible and undermine a central pillar of the rule of law. Debevoise provides legal representation consistent with the profession’s best traditions of integrity and probity, and we will continue fearlessly to defend the interests of all our clients.”

CTFCFC, through its solicitors Atkins Thomson, said it was hired by Debevoise to “research the European Union sanctions landscape” but did not have contact with anyone else. “This was the extent of our involvement and to try to claim otherwise would be utterly false.”

There is no suggestion that Crosby personally worked on or was aware of the work on EU sanctions carried out by CTFCFC until it was revealed in media reports.

“Lynton Crosby was working exclusively on the 2015 general election campaign for the Conservative party at this time, and had no client involvement, outside of the Conservative party,” according to a statement provided by the Atkins Thomson law firm. “He was not aware of this research project by CTFCFC for Debevoise until reference first appeared in the media nor has he ever met or worked with Lord Goldsmith or Debevoise.”

How Russia became emboldened

Journalist and Russia expert Edward Lucas, who was among the first to contribute to the ISC inquiry in July 2018, told CNN his testimony to the committee centered on the role of lobbyists who were advocating in the UK on behalf of Russian clients with dubious sources of wealth.

In his two-hour, 45-minute oral testimony alongside Chris Donnelly, founder of the Institute for Statecraft, a UK-based non-profit that has in the past received UK government funding, Lucas said British authorities should increase their cooperation with other countries to tackle Russian subversion.

Other witnesses warned that Moscow was emboldened by British governments’ failures to take a tougher stance after a former Russian spy, Alexander Litvinenko, was fatally poisoned with a rare radioactive isotope in London in November 2006.

In March 2018, an ex-Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were the targets of a nerve agent attack in Salisbury, England that left one British citizen dead and prompted the UK and other countries to expel dozens of Russian diplomats. One witness to the ISC inquiry pointed out in evidence that Russia had successfully used on British soil both a chemical weapon (the Skirpal case) and radioactive material (Litvinenko), an achievement unmatched by any terrorist organization. “We are now in an accelerating downward spiral that needs to be checked,” that person’s testimony reads, according to a copy reviewed by CNN.

In Parliament on Tuesday, Pincher, the government minister, said Britain had taken firm action to counter the Russian threat. “The government are prepared to be robust and transparent with respect to Russia – look at the way we carefully collated, assessed, scrutinized and presented the evidence of the Kremlin’s involvement in the attacks in Salisbury and Amesbury, and at the way we built an international alliance that responded to that threat.”

The government’s decision not to publish the ISC report has given the UK government’s critics plenty of ammunition. The opposition Labour party’s foreign affairs spokeswoman, Emily Thornberry, said the report could raise difficult questions about links between Moscow and the leadership of Boris Johnson’s Conservative party, and suggested that his director of communications, Dominic Cummings, had questions to answer about a period he spent in Russia in the 1990s. Ministers should have published the report, she told Parliament on Tuesday, adding: “What have you got to hide?”

Replying to Thornberry, Pincher, the government minister, accused her of a “giving a rundown of her interest in smears and conspiracy theories.” He said the government had taken “robust” action to counter the threat from Russia.

Downing Street and the Conservative party both declined to comment when asked to provide a statement from Cummings.

The failure to publish the ISC report means that the credibility the committee attached to the witnesses, and the conclusions it drew from their testimony, will not now be known until well after the election. Members of the ISC are appointed by the government and must go through a strict vetting process. Grieve told Parliament this week that after the last election, in 2017, it took six months to reconstitute the committee.

Britain’s low-tech voting processes are not thought to be under threat – voters mark their choices with pencils on paper ballots. But some politicians argue that the ISC report has the potential to contain material that could influence voters’ choices at the poll. Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson told Britain’s PA news agency this week that the government should have published the report before the election.

“If there is information that we should know about what has happened in previous democratic events and who has tried to interfere, the public has a right to know and the government shouldn’t be keeping it a secret,” she said.