A week ago, it seemed like Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam might have been on the verge of being ousted.

While her government denied rumors that Beijing was drawing up plans to replace her, few would have denied Chinese President Xi Jinping had cause: Lam has repeatedly admitted responsibility for the months-long political crisis rocking the semi-autonomous Chinese city, even reportedly offering to resign in the early days of the demonstrations, as large numbers of people took to the streets to protest an extradition bill she sponsored.

But on Monday, Xi sent a resounding message: Lam is here to stay.

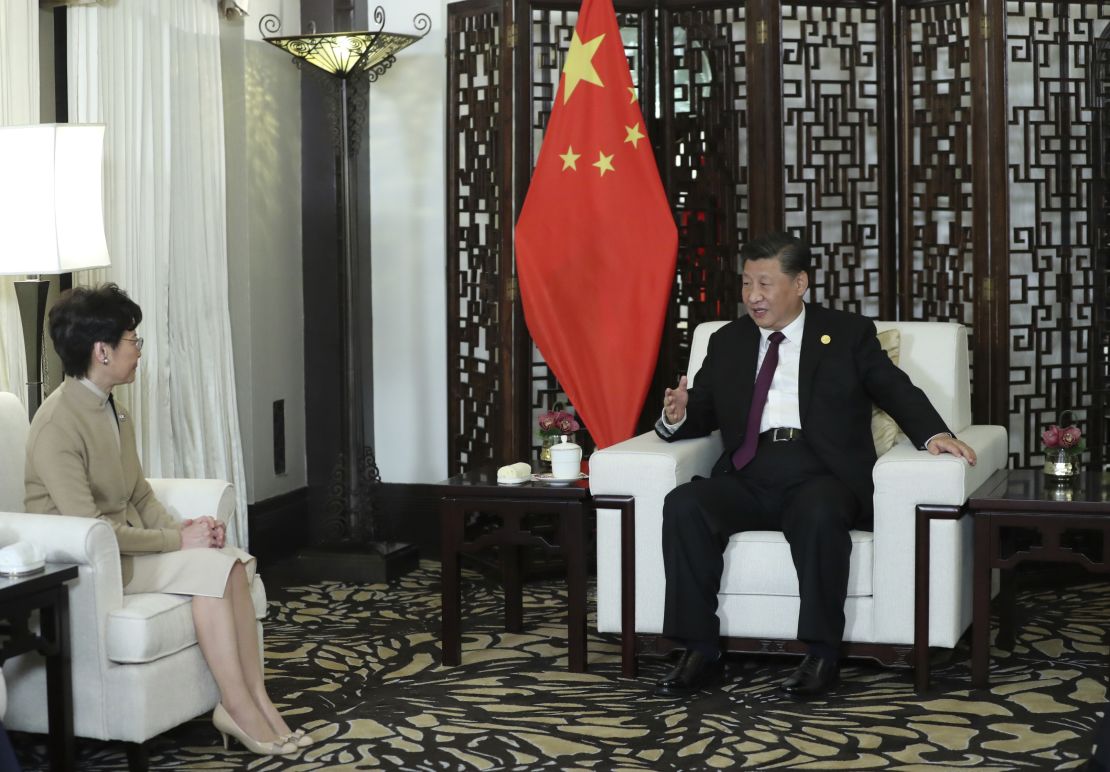

Xi “voiced the central government’s high degree of trust in Lam and full acknowledgment of the work of her and her governance team,” according to state-run news agency Xinhua, which also published a photo of the pair shaking hands and smiling.

Beijing’s decision to stick by Lam makes sense, replacing her would have opened a can of worms in an already unstable environment. But in a city where many see the hand of China in most government policies and pronouncements – and distrust them for this very reason – Xi’s full-throated endorsement could risk underlining for protesters just how much Lam is Beijing’s instrument.

Stay another day

It’s hard to imagine another political system where a senior politician could – by their own admission – have created the level of unrest that Carrie Lam has wrought in Hong Kong, and still keep their job.

“This is not something instructed, coerced by the central government,” Lam said of her disastrous extradition bill, in a recording of a private speech leaked to Reuters in September. “If I have a choice, the first thing is to quit, having made a deep apology.”

She didn’t – or was not allowed to – quit, and speaking in public after the recording leaked, Lam said she would “rather stay on and walk this path together with my team and the people of Hong Kong.”

But rumors that she had attempted to resign or was on the verge of being replaced have dogged her ever since, and it’s not hard to see why.

That no Hong Kong officials have lost their jobs over the crisis contrasts sharply with protests elsewhere in the world. In the past three months, protests in Puerto Rico brought down Governor Ricardo Rosselló in a matter of days; Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri stood down after less than two weeks of unrest, and Chilean President Sebastian Pi?era sacked his whole cabinet in response to widespread and occasionally violent demonstrations.

While it may appear surprising that no official has been asked to fall on their sword in the former British colony, the unwillingness to get rid of Lam makes sense.

Her departure would cause more problems for Beijing than it would solve.

Under the city’s constitution, if the office of chief executive becomes vacant, a successor must be selected “within six months.” Lam and all of her predecessors were chosen by an “election committee” which purports to represent a broad swath of society, but is dominated by pro-Beijing figures and follows the central government’s lead.

This situation has long been a point of contention in Hong Kong. An attempt to reform it ended with acrimony in 2014 when Beijing refused to allow candidates to stand without being pre-approved, kick-starting the months-long Umbrella Movement protests.

It’s possible that an interim chief executive could be appointed, such as when the city’s first leader after its handover from British to Chinese rule, Tung Chee-hwa, resigned in 2005. His successor Donald Tsang served out the rest of Tung’s term, and was subsequently reappointed for a full five-year term in 2007.

Regardless of how Lam were to be replaced, a rearranging of the top post would focus attention on the fifth of the protesters’ demands: universal suffrage.

Chinese democracy

If getting rid of Lam risked further inflaming protests in Hong Kong, Xi’s very public, very enthusiastic endorsement of her could do the same.

Lam’s resignation was called for in the early days of the protests but has largely been displaced by other demands – particularly an investigation into allegations of police brutality. Nevertheless, her popularity is in the doldrums, with her net approval rate at minus 71 points, according to polling by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute.

All Hong Kong chief executives are somewhat trapped between enacting the will of the people they in theory represent, and following Beijing’s orders when the requirements of the Chinese state contradict that will. A more malleable political system might have given Lam an easy public win over Beijing on some inconsequential issue, in order to prop up her autonomous bonafides. But whenever it has come down to Hong Kong vs China in recent years, the decision has always gone Beijing’s way.

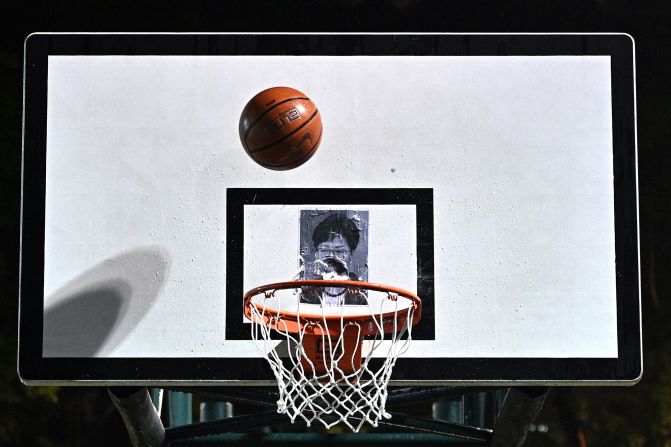

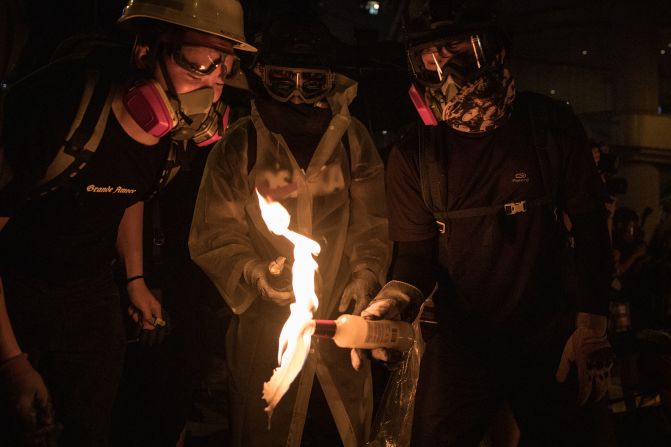

In pictures: Hong Kong unrest

Such contradictions have only become more heightened under Xi, who has taken a firm line on Hong Kong, cracking down on any suggestion of greater autonomy for the city, let alone independence, as a minority of protesters have advocated for.

But while Xi’s endorsement of Lam may help her exercise a firmer hand within government and bring pro-Beijing political parties in line ahead of district council elections later this month, it could have a galvanizing effect on protesters, who will see it as a confirmation of what they’ve been saying from the beginning: that Lam is a mere figurehead carrying out Beijing’s wishes.

“It is a cruel fact that most Hong Kongers consider Lam a puppet doing Beijing’s bidding instead of accurately reflecting the people’s views to her bosses,” commentator Michael Chugani wrote earlier this month. “Since the crisis erupted over her now-dead extradition bill, everything she has done proves rather than disproves that fact. She has not demonstrated in any way that she is on the side of the people or dares to stand up to her bosses.”

With his handshake, Xi has underlined his support of Lam, and made it all the more unlikely that she could ever challenge him.