Plastic milk bottles are being recycled to make roads in South Africa, with the hope of helping the country tackle its waste problem and improve the quality of its roads.

Potholes cost the country’s road users an estimated $3.4 billion per year in vehicle repairs and injuries, according to the South African Road Federation, as well as damaging freight.

In August, Shisalanga Construction became the first company in South Africa to lay a section of road that’s partly plastic, in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province on the east coast.

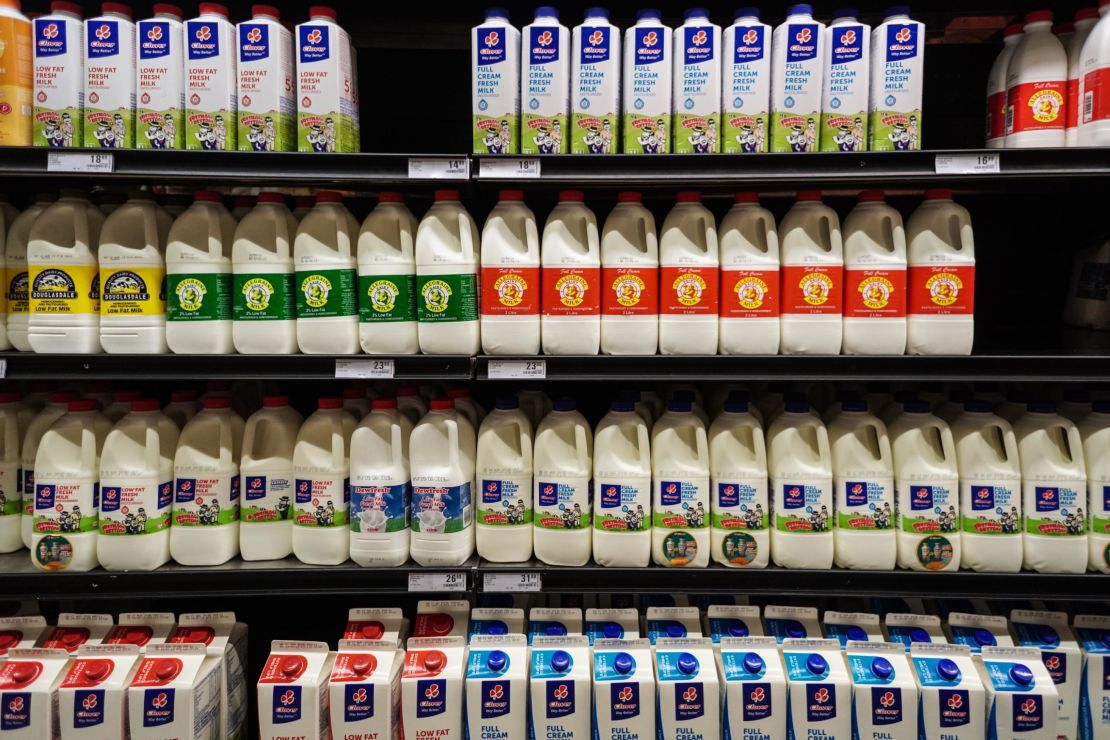

It has now repaved more than 400 meters of the road in Cliffdale, on the outskirts of Durban, using asphalt made with the equivalent of almost 40,000 recycled two-liter plastic milk bottles.

Road to recycling

Shisalanga uses high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a thick plastic typically used for milk bottles. A local recycling plant turns it into pellets, which are heated to 190 degrees Celsius until they dissolve and are mixed with additives. They replace six percent of the asphalt’s bitumen binder, so every ton of asphalt contains roughly 118 to 128 bottles.

Shisalanga says fewer toxic emissions are produced than during traditional processes and says its compound is more durable and water resistant than conventional asphalt, withstanding temperatures as high as 70 degrees Celsius (158F) and as low as 22 below zero (-7.6F).

The cost is similar to existing methods, but Shisalanga believes there will be a financial saving as its roads are expected to last longerthan the national average of 20 years.

“The results are spectacular,” says general manager Deane Koekemoer. “The performance is phenomenal.”

Unlike in Europe, for example, where recyclable plastic is often collected directly from homes, in South Africa, 70 percent is sourced from landfill. The plastic will only be taken from landfill if there is somewhere for it to go – such as into roads. Shisalanga says that by turning bottles into roads it is creating a new market for waste plastic, allowing its recycling plant partner to take more out of the nation’s dumps.

Kit Ducasse, control technician at the KZN Department of Transport – which commissioned the plastic repaving – is “impressed” with the road and has now commissioned a highway on-ramp in addition to the first road. “It’s working so well,” he says. “Time will tell, but what I’ve seen is great news.”

Shisalanga has applied to the South Africa National Roads Agency (SANRAL) to lay 200 tons of plastic tarmac on the country’s main N3 highway between Durban and Johannesburg and is awaiting approval for the project.

If it meetsthe agency’srequirements, the technology could be rolled out across the nation. Since SANRAL’s standards are so high, Shisalanga hopes it would then be able to meet the strictest regulations across the world.

Tackling the plastic problem

India began laying plastic roads 17 years ago, and the concept has been tested in locations across Europe, North America and Australia. But there are concerns over potential carcinogenic gases created during production and the release of microplastics (tiny particles of plastic) as the roads wear away.

“Such issues have to be ruled out, otherwise we’re going to contribute to and not alleviate the national environmental waste problem,” says Georges Mturi, senior scientist at CSIR.

Shisalanga has spent five years researching the technology. Its technical manager Wynand Nortje says its method of melting the plastic into the bitumen modifier minimizes the risk of microplastics. “The performance of our plastic mix is better than traditional modifiers, the fatigue seems improved and resistance to water deformation is as good or better,” he adds.

Roads are one of many creative solutions to reusing plastic waste. Companies around the world are turning it into bricks, fuel and clothing.

Some other international companies have even found ways to repurpose so-called “non-recyclable” plastic into roads. But Mturi at CSIR believes this is currently too risky in terms of emissions and microplastics, because the properties of this plastic are so variable.

Still, Koekemoer hopes to expand into using non-recyclable plastic in the future, allowing the company to get even more waste plastic out of the environment.

“We’re taking plastic out of our dumps (landfills) and we’re reducing our pollution problem, and to top it off we’ve produced a product that’s far superior to alternatives,” says Koekemoer. “We’re leading the global curves.”