It was 4 a.m. when 16-year-old Yoo Chae-rin realized she had been on her phone for 13 hours. In less than three hours, she had to be up for school.

The South Korean high school student knew she had a problem, so she enrolled in a government-run camp for teenagers who can’t put their phones down.

“Even when I knew in my head I should stop using my smartphone, I just kept going,” Yoo said. “I couldn’t stop, so I’d be on it until dawn.”

South Korea has one of the highest ownership of smartphones in the world. More than 98% of South Korean teens used one in 2018, according to government figures – and many are showing signs of addiction.

Last year, around 30% of South Korean children aged 10 to 19 were classed as “overdependent” on their phones, according to the Ministry of Science and Information and Communications Technology (MSIT). That means they experienced “serious consequences” due to their smartphone use, including a decline in self-control.

It’s those children – like Yoo – who qualify for a place on government-run camps to treat internet addiction. The program started in 2007 and expanded in 2015 to include smartphones.

This year, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family held 16 camps across the country for about 400 middle and high school students. For some parents, it was a last resort.

“I think they send kids here because of their desperate desire to get an expert’s help,” said Yoo Soon-duk, Director of Gyeonggi-do Youth Counseling & Welfare Center, which runs a camp for teens in the northern Gyeonggi province.

Sleepless and scrolling

Yoo had been an average student in middle school, but by high school she had sunk to the bottom of the class. She would stay up late, scrolling through her Facebook feed, playing with South Korean camera app Snow and talking with friends on instant messaging service KakaoTalk.

“I felt like my sense of reality was fading,” said Yoo. “Even when I had a fun and productive day (with my friends), it felt like a dream.”

Her father, Yoo Jae-ho, became increasingly worried about her. “There wasn’t much conversation among the family,” he said. “If I talked to her about her phone, there would be an argument.”

He set a time limit of two hours a day for smartphone use, but his daughter still found ways to get around it.

It was Yoo Chae-rin’s idea to join the camp in July. At the gate, she handed in her phone for the first time in years and started a 12-day detox.

Detox camp

South Korean internet camps are free, aside for a 100,000 won ($84) fee for food. Boys and girls are sent to separate camps, and each caters for around 25 students.

At camp, the teenagers are encouraged to participate in scavenger hunts, arts and crafts activities, and sports events. They also have to attend compulsory one-on-one, group and family counseling sessions to discuss their phone usage. Then, for 30 minutes before sleep, the campers meditate.

Many of the camps are held in youth training centers, away from the city, in green, leafy settings to help the young addicts switch off. Yoo’s camp was held in the city of Cheonan at the National Youth Center of Korea, which has an indoor swimming pool and sports ground.

Camp director Yoo Soon-duk said for the first few days the teenagers have an “agonized look” on their faces. “From the third day, you can see how they change,” she said. “They (start to) enjoy hanging out with friends.”

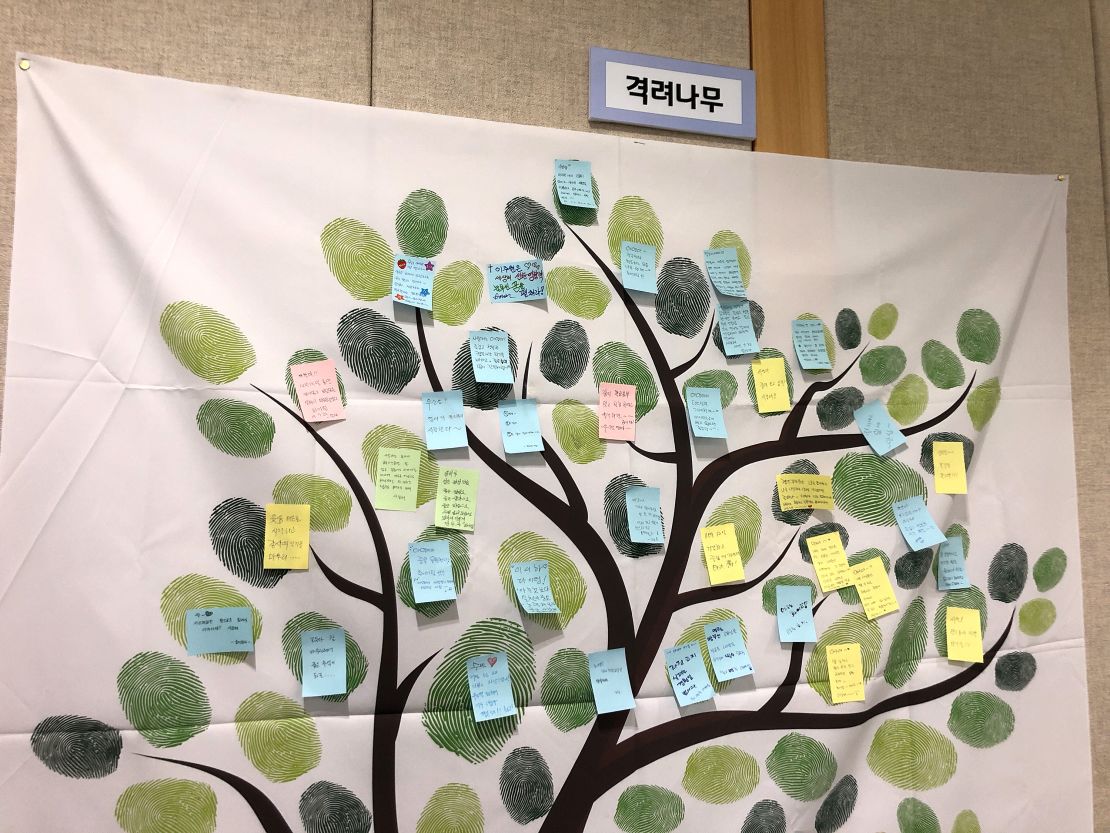

On a wall at the Cheonan camp, parents had left messages on a “tree of encouragement.”

“We hope that the camp will be a time to reflect on yourself and love yourself,” read one. Another – more ominous – message said: “Go Yong-joo! Don’t escape.”

While this camp is for teenagers, there are separate camps for elementary students, and the National Center for Youth Internet Addiction Treatment offers programs during the semester.

Why South Korea’s teens are so addicted

South Korea is not the only country where teenagers are hooked on phones – worries are growing about excessive smartphone use worldwide.

In 2015, 16% of 15-year-olds in OECD countries spent more than six hours online each day outside school hours, according to a report published in 2017. On weekends, the figure rose to 26%.

In South Korea, societal pressures are exacerbating the problem. There, children face a heavy academic workload and have few ways to relax. At the end of the school day, many are sent to cram classes, leaving little time for other activities.

In 2015, just 46.3% of 15-year-old South Korean students reported exercising or practicing sports before or after school – the lowest percentage of all 36 OECD countries.

Lee Woo-rin, a 16-year-old student who attended the same camp as Yoo Chae-rin, said she used her smartphone to relieve stress from school. “I temporarily forget my stress when I’m on my phone,” Lee said. “But the moment I stop using it, things that made me upset come back to my mind. It became a vicious cycle.”

Dr. Lee Jae-won, a psychiatrist who treats smartphone addiction, said that cycle was a symptom of addiction. When humans are stressed, it reduces dopamine in the brain, prompting them to seek other forms of satisfaction. Because teens don’t have other ways to relieve stress, they use their smartphones, he said.

“At first, smartphones comfort them, but they eventually think that a smartphone is enough to make them happy,” Dr. Lee said. “This leads them to give up school or studies.”

The problems with addiction

In the short term, a smartphone obsession can impact school grades, but the struggle to put down their phones can also have longer term effects for teens.

Over time, internet addicts can become socially isolated and suffer symptoms of withdrawal including “feelings of anger, tension, anxiety and/or depression,” according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

“There’s a high chance that they will live alone after losing family, jobs and friends,” said Dr. Lee.

Not spending time with their family and friends could mean they don’t develop the ability to solve interpersonal conflicts, said Yoo, the camp director. She recalled one teenage camp attendee who threatened to take his own life if he couldn’t leave the camp.

“For him, a smartphone was a bridge to society,” she said.

The South Korea government hopes that treating addiction early can prevent problems in the future.

“Later, when (these adolescents) grow up and have a hard time performing their social roles, not only is there a damage to an individual, but also the nation’s resources will be spent in order to support them. It’ll be a double loss,” said Kim Seong-byeok, the chief of the department that oversees the camps at the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family.

After camp

One month after the camp, Yoo said she only uses her phone for two to three hours a day, compared to around six to seven hours before.

One of the camp’s counselors helped her to understand why she was spending so much time online – as soon as she got bored with one app, she’d switch to another, then another, then another.

“Before, even if I thought in my head that I should stop, I couldn’t,” she said. “But now, if I want to stop, I’m able to stop right away.”

However, Yoo is not sure how effective the detox was for her fellow campers. “I had two roommates. As soon as the camp was over, one (of them) didn’t even say bye to me properly and ran out to use her smartphone,” she said.

According to psychiatrist Dr. Lee Jae-won, the camp’s long term benefits depend on how willing the teenagers are to change their habits. Those who still can’t control their need to use smartphones after the camp may need to seek medical help, he said.

Yoo said friends who went willingly to camp had noticed an improvement in their phone habits. However, she couldn’t say the same for those who fought the process.

“For friends who were forced to go because of their parents, I think the camp wasn’t that effective for them.”

CNN’s Lee Ji-su, Park Ji-min, Kim Na-yeong and Shin Jae-eun contributed reporting.