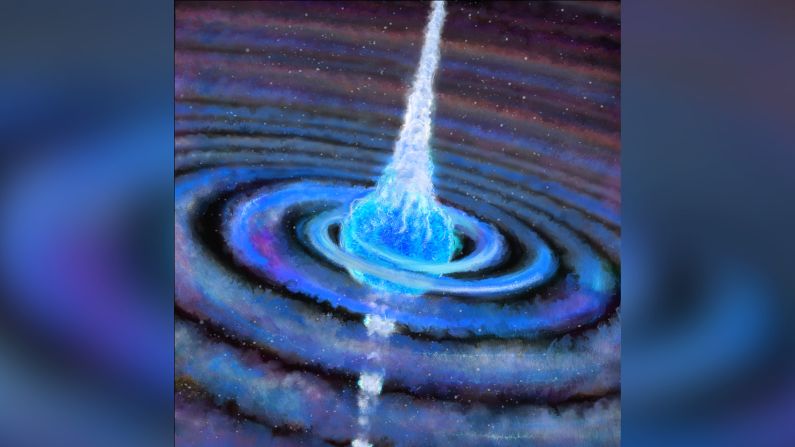

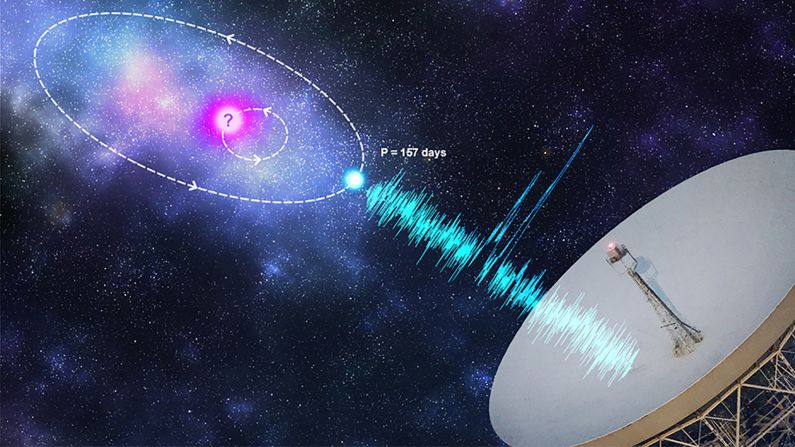

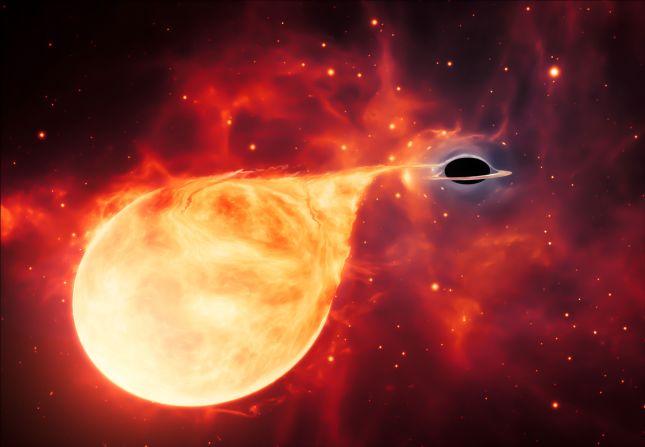

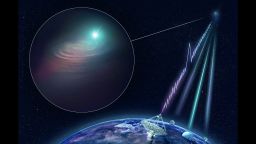

While tracing the signal of one space mystery, called a fast radio burst, it led astronomers to another intriguing observation.

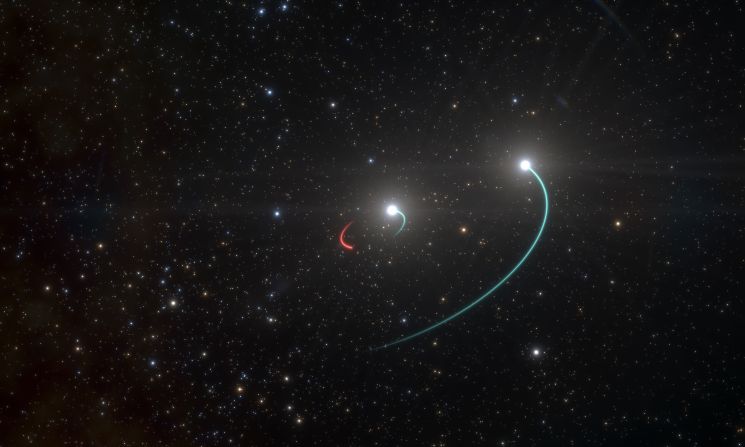

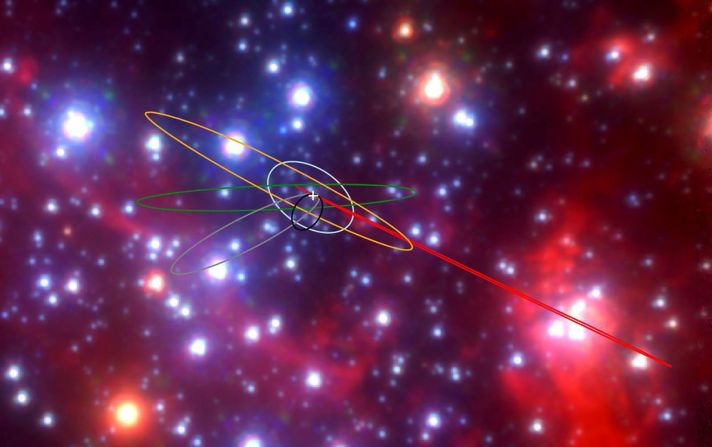

These fast radio bursts are only millisecond-long radio flashes, and such rapid bursts themselves aren’t rare in space. But finding out where they came from is incredibly difficult. In the last year, two have been traced back to their host galaxies. And astronomers still don’t know exactly what causes the pulses.

People love to believe that they’re from an advanced extraterrestrial civilization, and this hypothesis hasn’t been ruled out entirely by researchers at Breakthrough Listen, a scientific research program dedicated to finding evidence of intelligent life in the universe.

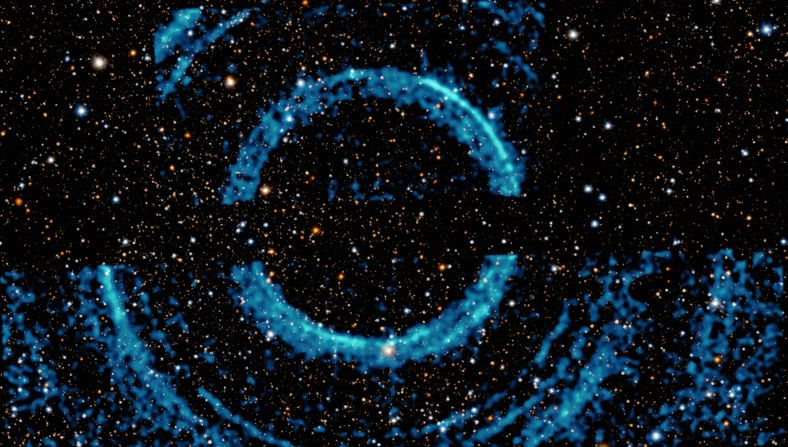

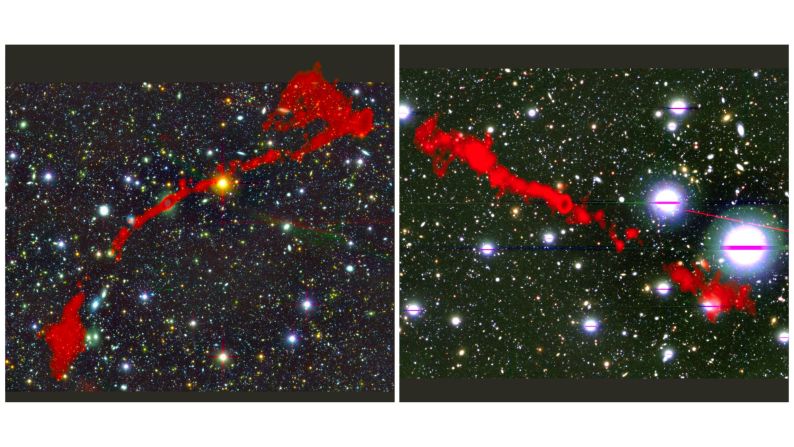

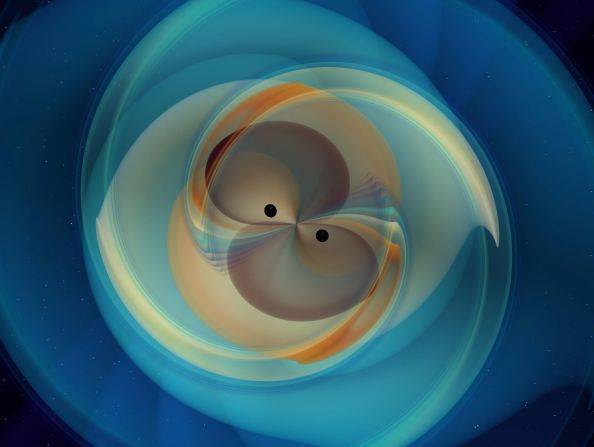

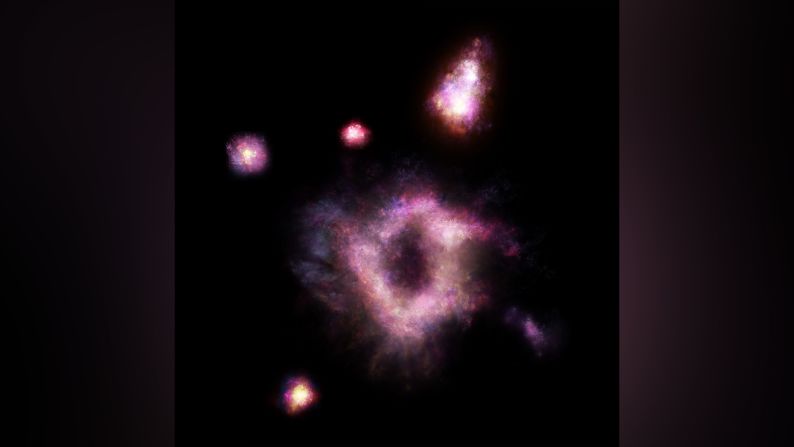

Follow-up observations of a fast radio burst designated FRB 181112, originally pinpointed in November 2018, revealed that the pulses traveled through a massive galactic halo while heading towards Earth. The astronomers were able to study the radio signal itself to learn more about the halo.

A study, including the findings about the radio burst and galactic halo, published Thursday in the journal Science.

“The signal from the fast radio burst exposed the nature of the magnetic field around the galaxy and the structure of the halo gas. The study proves a new and transformative technique for exploring the nature of galaxy halos,” said J. Xavier Prochaska, study author and professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California Santa Cruz.

Data from the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder radio telescope and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope provided the data necessary to study the radio burst’s trajectory.

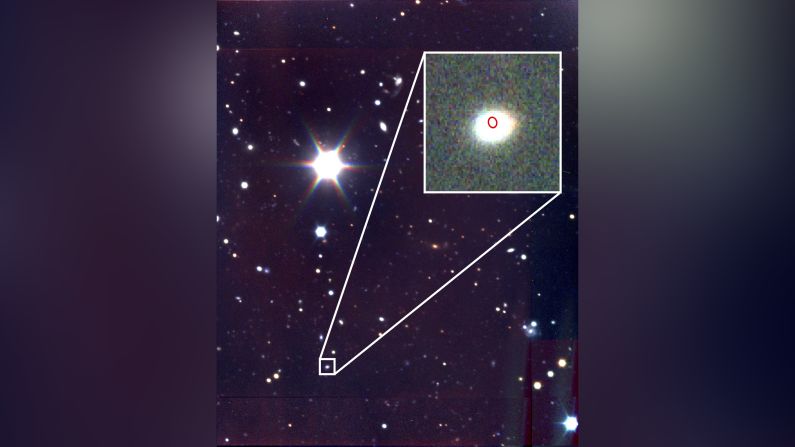

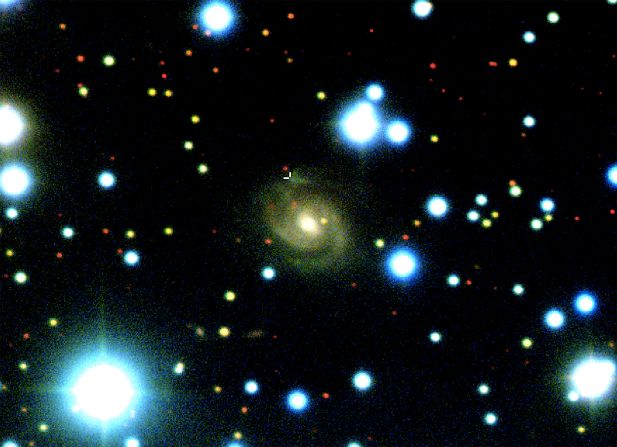

“When we overlaid the radio and optical images, we could see straight away that the fast radio burst pierced the halo of this coincident foreground galaxy and, for the first time, we had a direct way of investigating the otherwise invisible matter surrounding this galaxy,” said Cherie Day, study co-author and a PhD student at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia.

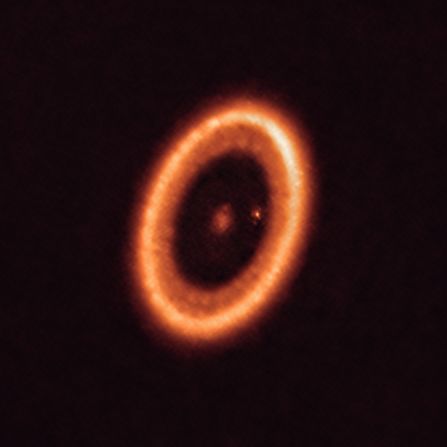

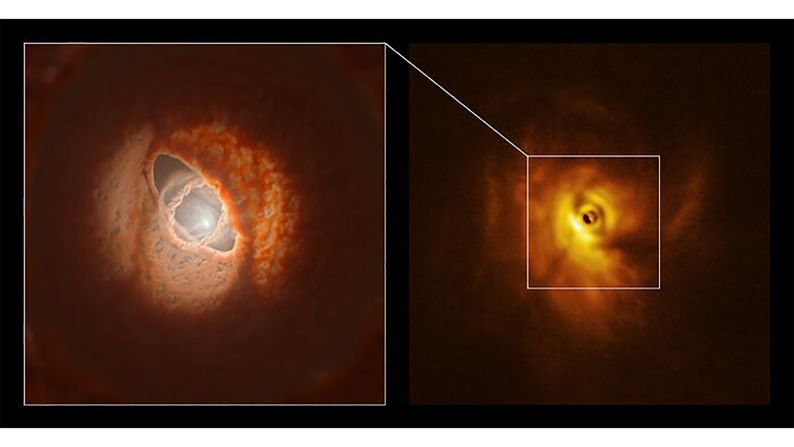

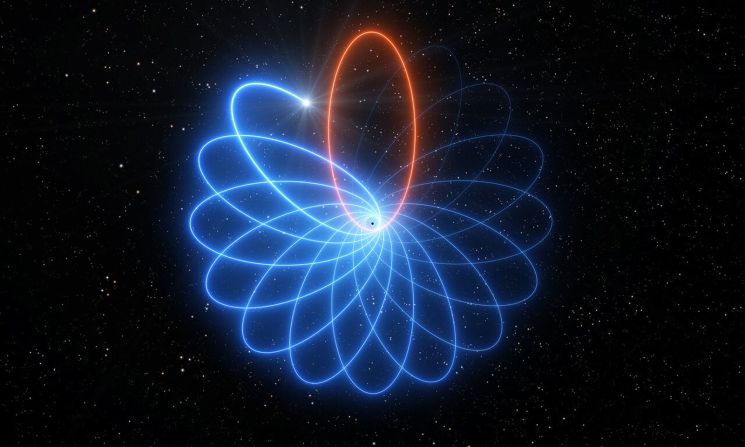

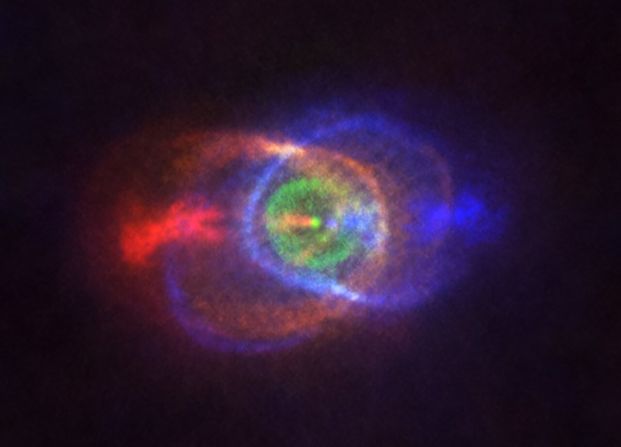

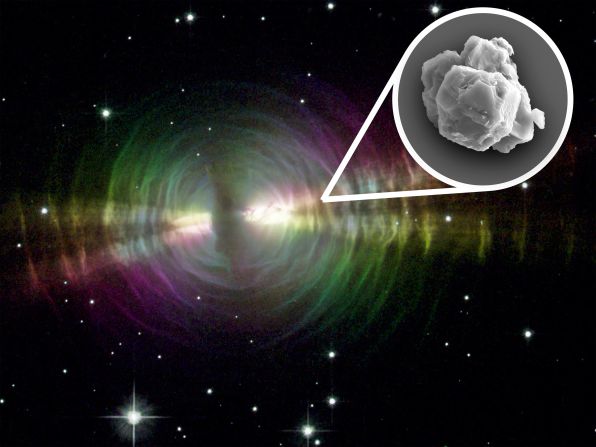

Galactic halos are enigmatic rings composed of hot, energetic gas that surround galaxies. Massive galaxies can be thousands of light-years across and the halos around them can be up to ten times larger in diameter.

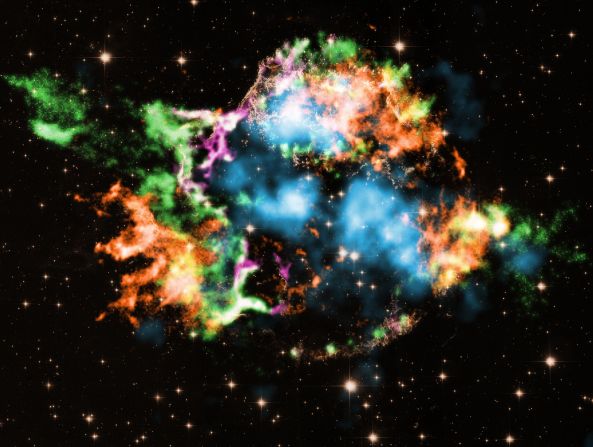

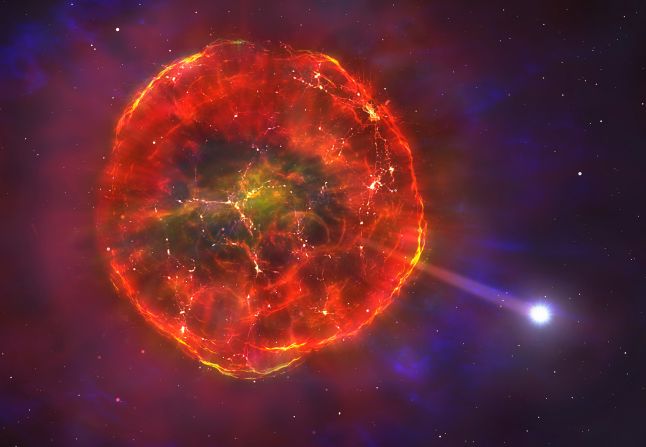

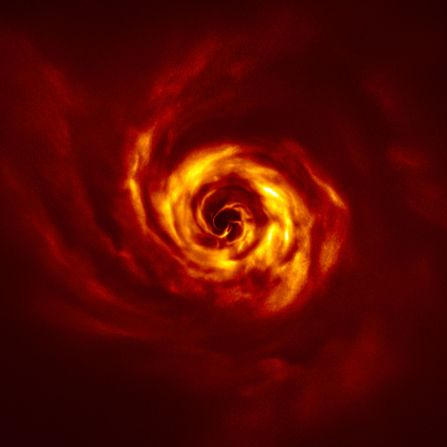

The gas in the halo is active, moving towards the center of the galaxy and helping with star formation. In turn, explosions, like a star’s supernova, can send material from the galaxy into the halo.

“The halo gas is a fossil record of these ejection processes, so our observations can inform theories about how matter is ejected and how magnetic fields are threaded through galaxies,” Prochaska said.

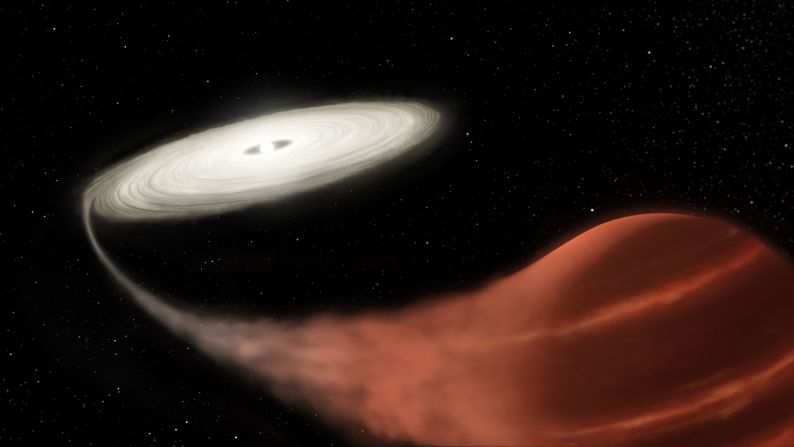

So what happens when a fast radio burst zips through a galactic halo? In this case, surprisingly, nothing.

“This galaxy’s halo is surprisingly tranquil,” Prochaska said. “The radio signal was largely unperturbed by the galaxy, which is in stark contrast to what previous models predict would have happened to the burst.”

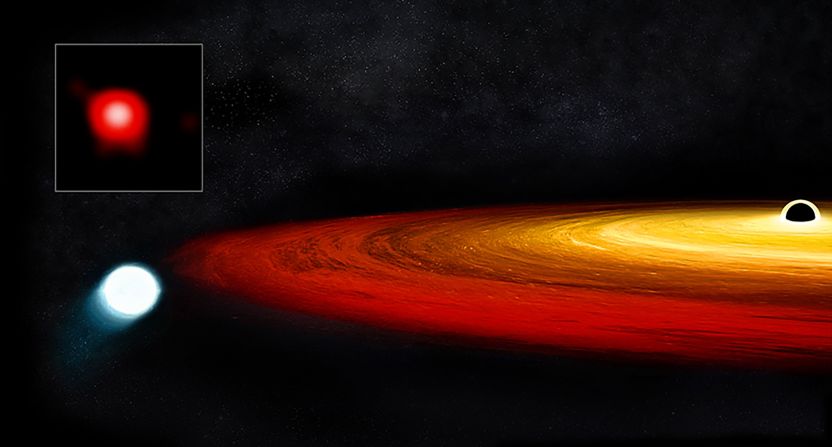

The astronomers thought the density of the gas in the halo would affect the speed of the radio signal.

“Like the shimmering air on a hot summer’s day, the tenuous atmosphere in this massive galaxy should warp the signal of the fast radio burst. Instead we received a pulse so pristine and sharp that there is no signature of this gas at all,” said coauthor Jean-Pierre Macquart, an astronomer at the International Center for Radio Astronomy Research at Curtin University in Australia.

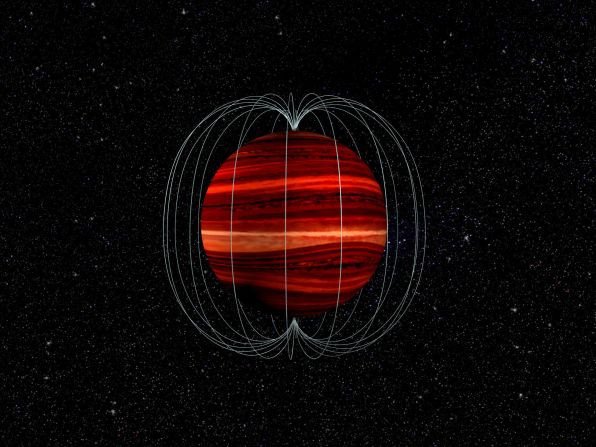

A previous model of galactic halos suggested they would be full of dense, clumpy gas clouds. But the pristine pulse didn’t enoucnter any. The radio burst signal also highlighted the fact that the magnetic field is one billion times weaker than that of a magnet on a refrigerator.

Surprisingly, these large halos are hard to see with telescopes. But the signal passing through the halo will allow astronomers to learn more about what happens in these gaseous regions of galaxies.

But the astronomers are also curious about whether this halo is an exception or represents the majority.

“This galaxy may be special,” Prochaska said. “We will need to use fast radio bursts to study tens or hundreds of galaxies over a range of masses and ages to assess the full population.”