Certain hormone replacement therapies have long been tied to an increased risk of breast cancer. Now, new research suggests that in some cases, that risk can persist for more than a decade.

The research, published in the journal The Lancet on Thursday, found that risks increased steadily the longer the hormone replacement therapy was used, and were greater for estrogen-progestogen hormone therapies than for estrogen-only hormone therapy. Every type of hormone replacement therapy, except for vaginal estrogens, was associated with excess breast cancer risks.

The menopausal transition most often begins between ages 45 and 55, causing symptoms to appear due to changes in the body’s production of the sex hormones estrogen and progesterone. Sometimes women take hormone replacement therapy, also called HRT or menopausal hormone therapy, to help relieve symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes, night sweats, pain during sex and vaginal dryness. Those symptoms can be mild in some women but can impact the wellbeing of others. The hormones most commonly used to treat symptoms of menopause are estrogen and progesterone.

‘Excess risk persisted for more than 10 years’

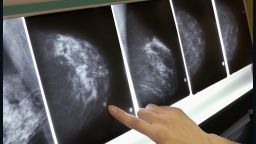

The new research was based on an analysis of data from 58 previously published studies on hormone replacement therapy, which included more than 100,000 postmenopausal women with invasive breast cancer.

The researchers found that for women of average weight in Western countries, five years of using estrogen plus a daily progestogen hormone therapy, starting at age 50, was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer up to age 70.

Specifically, the research suggests that the estimated incidence of breast cancer at ages 50 to 69 was tied to an increased risk – from 6.3% of women who never used hormone replacement therapy to 8.3% of those who used the therapy daily for five years.

That’s an increase of about one extra cancer case in every 50 users of the therapy, according to the research.

Similarly, five years of using estrogen plus intermittent progestogen hormone therapy was tied to an increased risk, from 6.3% to 7.7%, representing an increase of one extra cancer case in every 70 users of the therapy, the research suggests.

The research also suggests that five years of using an estrogen-only therapy was tied to an increased risk, from 6.3% to 6.8%, which would be an increase of one extra cancer case in every 200 users of the therapy.

Even if therapy is stopped at some point, “some excess risk persisted for more than 10 years,” the researchers wrote.

The new research showed just an association between hormone replacement therapy and breast cancer – not a causal relationship. More research is needed to determine whether hormone replacement therapy actually caused increases in breast cancer incidence.

If the associations in the new research are largely causal, the data suggests that menopausal hormone therapy used in Western countries may have caused about 1 million breast cancers out of the total 20 million that have occurred worldwide since 1990.

Weighing the risks and benefits

The findings came as no surprise to Dr. Otis Brawley, Bloomberg distinguished professor of oncology and epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who was not involved in the new research.

“For 18 years now I have been trying to convince women that they don’t want to start postmenopausal estrogens, and I’ve been encouraging women who have hot flashes to try to resolve those hot flashes through other medical means,” Brawley said.

“Now there’s some women who have hot flashes that are so significant that giving them estrogen actually is worth the risk,” he said. “Virtually everything we do in medicine has a risk and a benefit to it, and when the benefit starts getting to be clearly higher than the risk then perhaps you ought to do it, but when the benefit is not clearly higher than the risk, I try to avoid using it.”

In general, the US Food and Drug Administration says not to take hormone therapy if you have problems with vaginal bleeding; have or had a history of certain cancers; have or had a blood clot, stroke or heart attack; or have a bleeding disorder, liver disease or allergic reactions to hormone medicine.

For women who are already taking a hormone replacement therapy and might have some concerns, Brawley said to talk to your doctor.

The new research should help both women and their doctors in deciding whether or when to start hormone therapy and which preparation to take – estrogen and progestogen combined or estrogen alone, Dr. Janice Rymer, gynecologist and vice president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in the United Kingdom, said in a written statement distributed by the Science Media Centre.

“Women must be informed of the small increase in risk of breast cancer so they can weigh these up against the benefits that they may have from taking HRT,” Rymer said in the statement. She was not involved in the research.

“These findings should not put women off taking HRT if the benefits – such as protection of bones and decrease in cardiovascular risk – outweigh the risks,” she said. “To put the risk into context, a woman has greater risk of developing breast cancer if she is overweight or obese compared to taking HRT.”

‘We would urge patients not to panic’

The Royal College of General Practitioners in the United Kingdom urged women not to panic as a result of the new research.

“The link between HRT and an increased risk of breast cancer has been known for some time. But it is a complex relationship,” Martin Marshall, vice chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, said in a written statement in response to the research.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“There is still a lot of evidence to suggest that HRT is safe and effective, and current clinical guidelines recommend it as an appropriate treatment for some women going through menopause. Nevertheless, it is important that clinical guidelines are evidence-based, and that this study is taken into account as clinical guidelines are updated and developed,” he said. “We would urge patients not to panic as a result of this research, and to continue taking HRT as it has been prescribed to them – and we would urge prescribers to do so as normal, until clinical guidelines recommend otherwise.”