Eleven days after the Indian government suspended all communications in Indian-controlled Kashmir, the disputed region still has no contact with the outside world.

Millions of residents in the Kashmir Valley – one of the most militarized regions in the world – are living behind a virtual curtain. Unable to access the internet, send letters, or even make calls using a fixed line, India’s most volatile region has vanished from the modern world.

“No telephone lines are working, no internet is working, no broadband is working. There is a virtual clampdown. There is no communication link… My own office is not functioning and I am not in touch with a single bureau member in Srinagar,” said Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor of the Kashmir Times.

In an unprecedented move, the Indian government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi cut off the entire Jammu and Kashmir region at midnight on August 5. Kashmiris living outside the territory have not been able to reach friends and family.

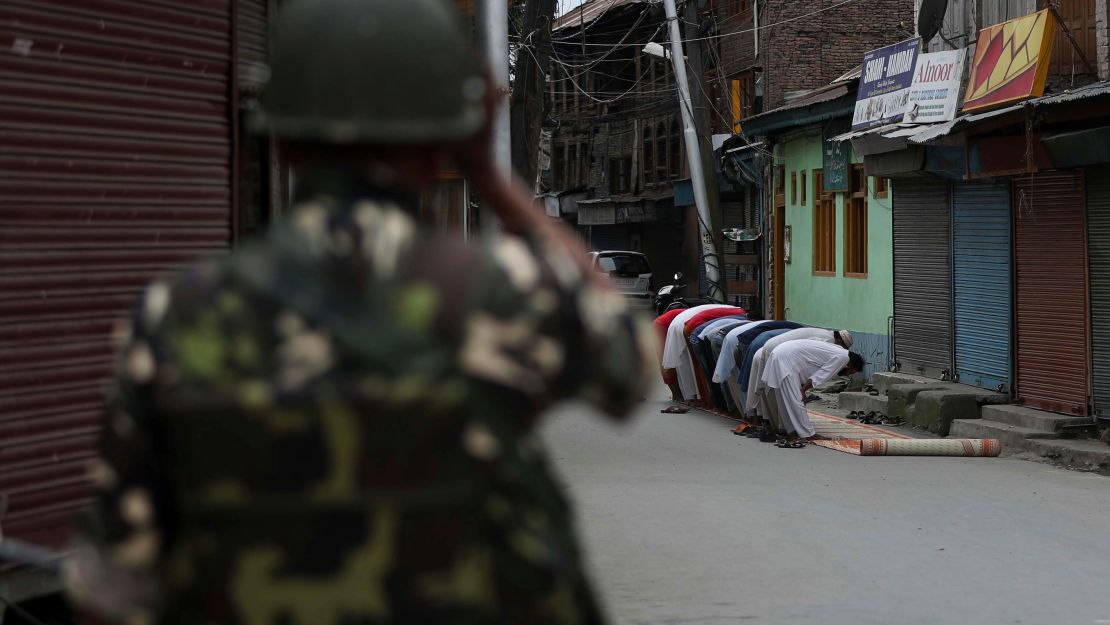

The move was preceded by tens of thousands of Indian troops moving into the valley, establishing check points every few hundred feet and laying down coils of wire at every corner to restrict the movement of vehicles.

A curfew has forced residents to mostly stay inside their homes, stepping out only to buy medicines or basic groceries.

Officials have repeatedly said that the lockdown will be lifted in phases over the next few days but have not provided a definitive timeline, leaving the entire region in confusion. Most newspapers have been unable to report or publish information across the region, especially from rural areas.

Less than 12 hours after the lockdown, Indian Home Minister Amit Shah announced in Parliament that the government was scrapping a constitutional article affording the state of Jammu and Kashmir special status.

Article 370 provided the state with semi-autonomy, which included a separate state constitution, its own flag and control over internal matters except for certain policy areas such as foreign affairs and defense.

Shah’s announcement was succeeded by the passage of a law reorganizing the state by downgrading it to a union territory.

In the Indian system, state governments retain significant authority over local matters but New Delhi has more of a say in the affairs of a union territory. The remote mountainous region of Ladakh, currently part of Jammu and Kashmir, will also be separated and turned into a standalone union territory.

Anger and confusion

Claimed by India and Pakistan in its entirety, Kashmir is one of the world’s most dangerous geopolitical flashpoints.

In 1947, after India’s independence from British colonial rule, the erstwhile ruler of Jammu and Kashmir was given an option to accede to either Pakistan or India and, in exchange for protection, chose the latter. But special provisions were added to the Indian constitution, under Article 370, to protect the rights of the territory’s residents.

The only Muslim-majority state in India, Jammu and Kashmir has erupted with violent protests over the past few years. Demanding accountability from New Delhi, protestors have stormed the streets, pelting Indian soldiers and police personnel with stones.

Activists who have recently visited the region say its residents are now angry both at what has happened with the scrapping of Article 370, and the way it was done.

“The manner in which it was done means that the Indian government is not willing to make any kind of concession. It will just have its way no matter what and they are prepared to enforce it. That is a big defeat,” said Jean Dreze, an economist who visited the region with a group of activists.

Fears of what may be happening in the valley, behind the latest blackout, have steadily increased with apprehension over the future.

“For now, protests are virtually impossible. Without communications, without any movement, people cannot gather and individual protests can be extremely dangerous… But I think people are waiting for a chance to protest although they know it may not be possible for some time,” said Dreze.

A report, published by Dreze and three other activists, describes an “intense and virtually unanimous anger” in the Kashmir Valley over the Indian government’s decision to abrogate Article 370, and the way it was done.

“It is very humiliating. The timing of it just before Eid. The people feel that they have been tied down and behind their backs this was done. Even though the entire purpose of that article was to prevent a unilateral takeover,” Dreze told CNN.

While the Kashmir Valley is familiar with internet blackouts, the latest all-encompassing ban on broadband, landlines and even cable TV has not been enforced before.

There have been 59 blackouts here so far this year, far more than anywhere else in India, according to the Software Freedom Law Center, India, an NGO.

It was never clear how long previous shutdowns would last. The longest blackout went on for 133 days in 2016, after Indian forces gunned down Burhan Wani, the 21-year-old leader of a militant separatist group.

“The economy is totally paralyzed right now. There is no employment, no income generation and I don’t think that that can go on for very long without consequences,” said Dreze.

Escalating geopolitical tensions

Pakistan, lying to the east has responded to India’s policy changes aggressively, with Prime Minister Imran Khan likening the ideology of India’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to that of Nazi Germany.

This “ideology of Hindu Supremacy, like the Nazi Aryan Supremacy, will not stop” in Indian-controlled Kashmir, “instead it will lead to suppression of Muslims in India and eventually lead to targeting of Pakistan,” he tweeted.

China, which shares a part of Jammu and Kashmir’s western border and controls 20% of the Kashmir region also protested India’s actions, with the Chinese Foreign Ministry accusing New Delhi of encroaching on Chinese territorial sovereignty.

Beijing warned India to “strictly abide by the relevant agreements reached by both sides, and avoid taking actions that would further complicate the boundary issue.”