Almost six million people are under threat from rising flood waters across South Asia, where hundreds of thousands of people have already been displaced as a result of heavy monsoon rains.

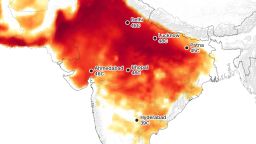

The flooding comes as India was still reeling from a weeks-long water crisis amid heavy droughts and heatwaves across the country which killed at least 137 people. Experts said the country has five years to address severe water shortages, caused by steadily depleting groundwater supplies, or over 100 million people will left be without ready access to water.

In Afghanistan, drought has devastated traditional farming areas, forcing millions of people to move or face starvation, while in Bangladesh, heavy monsoon flooding has marooned entire communities and cut-off vital roads. Especially at risk are the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees living in fragile, makeshift camps along the country’s border with Myanmar.

This is the sharp edge of the climate crisis. What seems an urgent but still future problem for many developed countries is already killing people in parts of Asia, and a new refugee crisis, far worse than that which has hit Europe in recent years, is brewing.

Monsoon disaster

Agriculture in South Asia has depended on the annual monsoon for centuries. If the rains arrive late, as they did this year, they can cause widespread drought and water shortages. Since the late 19th century, scientists and government agencies have sought to model and predict when the monsoon will come, a vital task in apportioning relief and assistance to the two billion or so people who depend on the monsoon for sustenance.

Climate change is making this task increasingly difficult, however. According to a study in the journal Nature, the warming of the Indian Ocean, the increasing frequency of the El Ni?o weather phenomenon, air pollution and changing land use across the subcontinent has led to steadily decreasing rainfall, increasing the variability of the monsoon and making it harder to accurately model.

Cruelly, as the overall amount of rain has decreased, leading to drought, the frequency of extreme rainfall, causing flooding and landslides, has actually gone up, the Nature study found.

Researchers said there had been a threefold increase in “widespread extreme rain events” over central India between 1950 and 2015, which brought with them a potentially “catastrophic impact on life, agriculture and property.”

“The overall intensity and frequency of extreme events are increasing over the region,” the study said, adding that projected changes showed “further intensification of extreme precipitation over most parts of the subcontinent by the end of the century.”

A combination of rising temperatures and more severe droughts and flooding is raising the very real question whether parts of India could soon be unlivable for humans. And its not just India, scientists predict extreme heatwaves that can kill even perfectly healthy people are becoming more common across South Asia, as well as much of the Middle East and North Africa.

Unequal effects

Climate change is no longer a future event. We already appear locked into 1.5C of warming, once hoped to be the top limit of human-caused climate change, and are now on path to blow through the 2C limit set by the Paris Agreement.

The unfolding climate emergency will affect the entire world, but it will not do so equally, or all at the same time. Parts of the globe will see manageable temperature spikes or variable weather, as others face deadly droughts, heatwaves, flooding and extreme weather. Those who survive these climate shocks may find local agriculture and infrastructure devastated, making them all the more vulnerable in future.

Rising sea levels and coastal flooding is expected to effect millions more in some of the world’s least developed countries.

According to the United Nations, more than 120 million people could slip into poverty within the next decade because of climate change, forcing them to “choose between starvation and migration.”

Researchers from Stanford University have previously warned that climate change is making poor countries poorer, widening global inequality between nations.

“We risk a ‘climate apartheid’ scenario where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger and conflict while the rest of the world is left to suffer,” said Philip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, last month.

But while the air conditioned, hurricane and typhoon-proofed cities in the developed world may be able to better cope with the immediate effects of climate change, they will not escape the ramifications of how the crisis unfolds in other countries.

Climate refugees

People affected by climate change will not stay put as their children drown or die of heat stroke or thirst. The Norwegian Refugee Council estimates that 26 million people are displaced by disasters such as floods and storms every year, or one person every second. By 2045, according to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, some 135 million people could be displaced as a result of land and soil degradation.

Most of those people become internally displaced, in effect refugees within their own country. But the numbers forced to flee across borders is on the rise – driven too by violence and persecution – reaching 70 million this year, a record high.

According to government documents published by the ABC this week, Australia alone may face up to 100 million climate refugees in the coming years, as large parts of the Indo-Pacific is hit by rising sea levels and extreme weather.

Australia – which is among the worst offenders for global emissions – has some of the most draconian policies for dealing with refugees in the developed world, housing them in offshore detention camps which have been denounced by the United Nations and human rights groups.

Other countries have reacted to existing refugee flows – many of which are already effected by climate change even if this is not widely discussed – with shifts to nativism and often violent anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Making matters worse, the UN’s Refugee Convention currently does not recognize those fleeing climate change as entitled to protection by international law. This could enable countries to refuse to offer sanctuary, or regard those entering the country as illegal immigrants.

South Asia is already suffering as a result of climate change, a crisis caused by the developed world’s consumption patterns and fossil fuel-driven capitalism. The effects of that crisis will not remain confined to the region for long, however, nor will the people already dealing with the sharp end of it.