As the sun rose on the morning of June 4, 1989, the Chinese people woke to a country which had changed overnight.

For seven weeks it had seemed like China was on the brink of a massive social change, but in just one night the dreams of hundreds of thousands of protesting students and workers were brutally crushed.

For about a decade, China’s economy had been steadily opening up and allowing small amounts of free enterprise in the Communist country, after years of strict state control under chairman Mao Zedong.

Directing the change was then-Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping, who wanted to see China grow prosperous by embracing some pro-market liberalization.

But when large-scale protests in Beijing called for greater social freedoms, such as freedom of speech and even democracy, Deng would prove far less enthusiastic.

The protests first began in April, triggered by the death of former Chinese Communist Party leader Hu Yaobang at the age of 73. Seen by the public as a champion for liberalization, Hu had been deposed two years earlier and his death on April 15 was widely mourned.

Three days later, thousands of grieving students marched through Beijing, calling for a more democratic government in Hu’s honor.

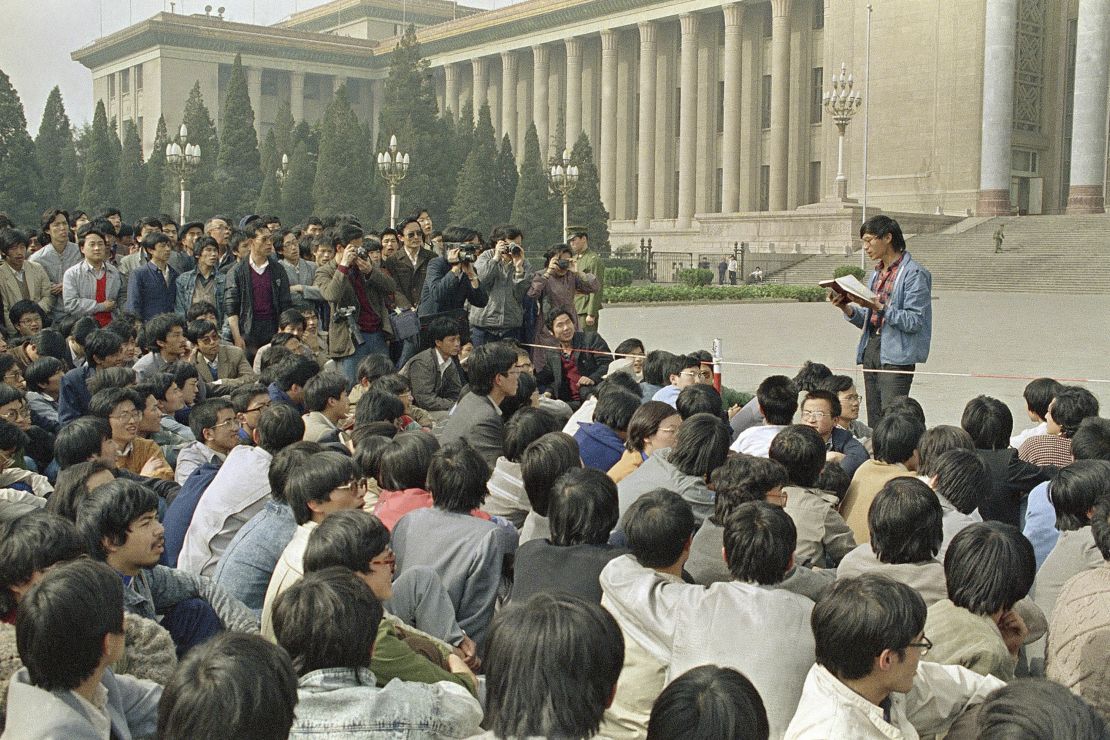

The protesters occupied Tiananmen Square, the massive public space in the center of Beijing which faces onto the Forbidden City, former home of the Chinese emperors, and the Great Hall of the People.

Over the coming month and a half, the numbers of protesting students and workers steadily grew. A rally on May 19 in the square drew an estimated 1.2 million people, leading then-Communist Party leader Zhao Ziyang to meet with them to plead for an end to the protests.

He began his now-famous speech by saying: “Students, we came too late. We are sorry.”

But he was ignored and hardline Premier Li Peng imposed martial law on the city the same day. Trucks of soldiers began to arrive in Beijing, but still the protests didn’t stop.

On May 30, in the center of the square, protesters built a 10-meter high statue called the Goddess of Democracy, to boost morale among the huge crowd.

In the end, the government moved swiftly. After a tense two weeks, on the night of June 3, convoys of armed troops entered Beijing with an aim to clear the square by whatever means necessary.

Blocked by civilians in the streets who were attempting to protect the students, the troops opened fire. Students, workers and other ordinary citizens fought back, setting fire to some military vehicles, but they were overwhelmed.

Witnesses told horrific stories of tanks driving over unarmed protesters and soldiers shooting indiscriminately into crowds.

No official death toll was ever released by the Chinese government, but human rights groups estimate it was the hundreds, if not thousands.

Many of the protest leaders were imprisoned, some of whom wouldn’t be released for more than a decade, and the government has worked hard to remove all mention of the massacre from Chinese history and media, seeing it as a threat to the legitimacy of its continued one-party rule.

So far, at least, it appears to have worked. On the 30th anniversary in 2019, no public memorials or events marking the day are expected in mainland China.

CNN’s Mohammed Elshamy contributed to this article.