Multiple times a day, every day, Ron Davis sits with his head bowed, waiting outside his son’s bedroom for a subtle signal that it’s all right to come in.

He opens the door to the space where Whitney has spent most of the last decade.

Whitney lies motionless on a simple bed, his head shaved and his frame emaciated. He’s fed by a tube directly into his stomach. His lips haven’t uttered a word in five years.

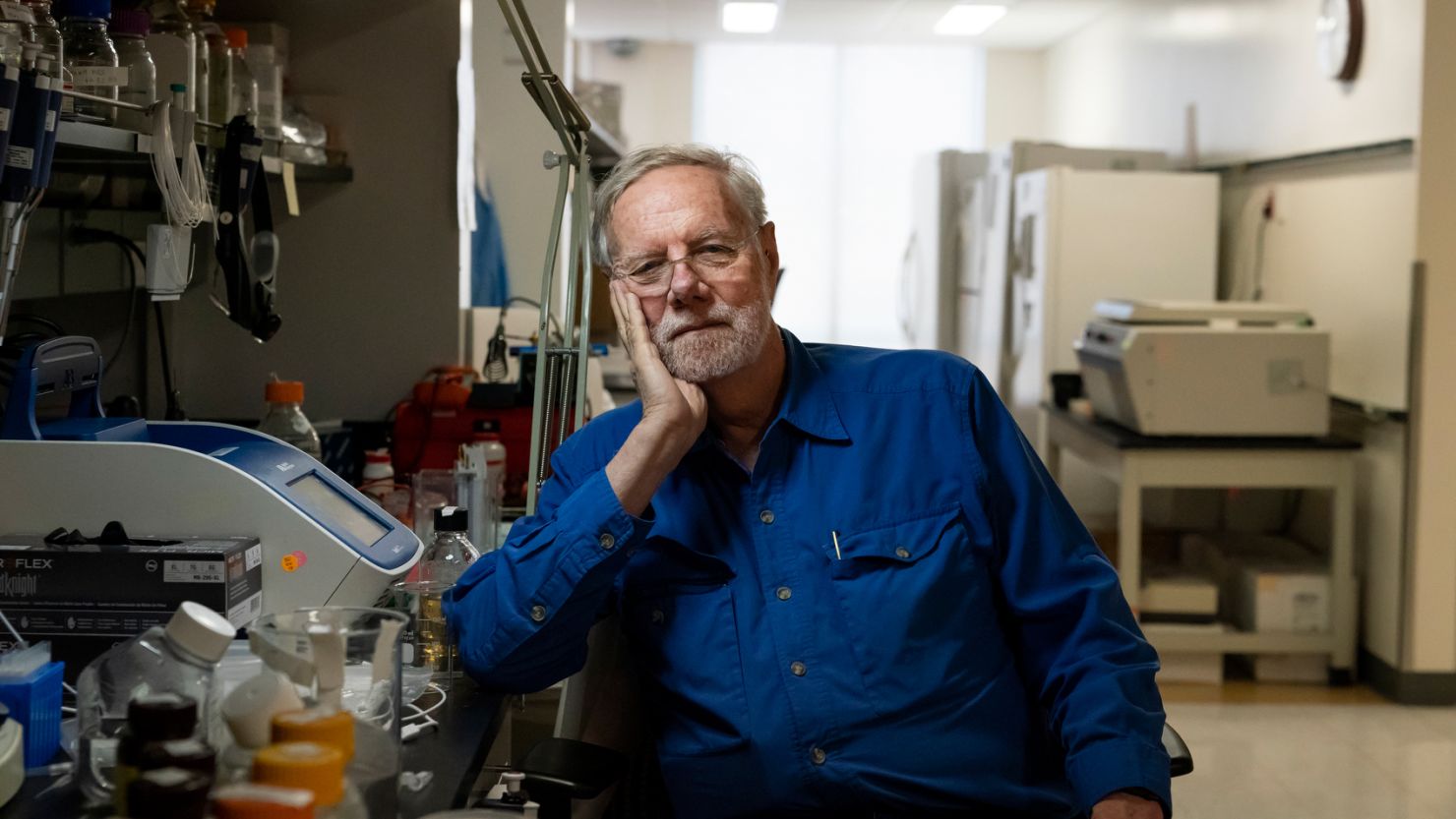

Davis, who is 77, leads a lab that invented much of the technology that powered the Human Genome Project. Now he and his wife spend much of their days caring for their 35-year-old son, who is immobilized by myalgic encephalomyelitis, or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Sunday is ME/CFS International Awareness Day. There is no cure. But Davis is leading a global push to root out the molecular basis of what is laying waste to Whitney and millions of other sufferers around the world so that scientists can better treat the disease.

Davis signals to his wife, Janet Dafoe, that Whitney is ready. She goes in and wipes her son’s face. She pulls the covers up toward his head while he lies motionless.

She fixes an IV bag to a pole, which will drip water into her son’s veins.

Davis sinks to his knees and takes Whitney’s socks off. He clips his son’s toenails. He washes his son’s feet.

For the couple, it’s a holy moment.

Davis led a revolution in science

Davis and Dafoe will celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary in July. Decades ago, they would have never predicted their current situation.

Now their everyday lives are consumed with caring for their son. At least one of them must be at home every day to attend to Whitney.

“My wife and I can’t go away together anymore,” Davis says. They used to go to the beach every year, but it’s been more than seven years since they last went. On basically a single income, they struggle with finances.

“It has turned my life upside down in many respects. I decided to terminate everything I was working on before Whitney got sick,” Davis says. “Everything is ME/CFS now. It’s an emergency kind of effort.”

The couple have spent their careers in and around Stanford University. Davis worked for decades in the school’s biochemistry and genetics department while Dafoe, who just turned 70, works as a child psychologist. She has scaled back her hours to about five hours a week to care for her son.

After his PhD at Caltech, Davis completed his postdoc at Harvard studying under Nobel Laureate Jim Watson of “Watson and Crick” fame, who was immortalized in science textbooks for co-discovering the double-helix structure of DNA in 1953.

Davis joined Stanford’s biochemistry department in 1972 as an associate professor and quickly began making a name for himself.

He co-wrote one paper that created a map with a new way to link genes to the traits they caused, which became a cornerstone of the field of genomics. It led Davis and his colleague to write a “proposal for a map of the whole human genome.” The National Institutes of Health turned them down in 1979, saying their plan was too ambitious.

But Davis kept innovating, eventually accumulating more than 30 patents for technology he developed.

Finally, the world caught up to his vision. The $3.8 billion Human Genome Project began in 1990, with Davis’ gene-sequencing technologies at its core. Completed in 2003, it launched a revolution in science. Handing researchers that foundational blueprint for human life gave biologists and doctors what up to that point was an unimagined power to diagnose, treat and ultimately prevent the full gamut of human disease.

Davis was shortlisted by The Atlantic, along with SpaceX founder Elon Musk and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, as someone tomorrow’s historians will consider today’s greatest inventors.

The same prescient mind that dreamed up the Human Genome Project now devotes days to what Davis calls “the last great disease to conquer.”

He may need all his brilliance to save his son.

But then his son got sick, and his priorities changed

Davis and Dafoe raised their two children in a quiet Palo Alto neighborhood. Each year they backpacked as a family in California’s Sierra mountains, disappearing for weeks at a time.

“I carried Whitney up there when he was young,” Davis says. On one of these trips 5-year-old Whitney impressed his father by walking nine miles in a single day. On another Sierras trip their baby daughter Ashley took her first steps at 5,000 feet above sea level.

“I haven’t gone in 10 years now,” Davis says. “I would love to do that with Whitney again.”

By 2008, Whitney, was 24 and living in a small town in Nevada, knocking on doors for then-Sen. Barack Obama’s presidential campaign.

But he often complained about being exhausted. A skilled photographer, Whitney captured images at Obama’s inauguration in 2009, but even then he could no longer work a full day.

After years of declining health, seeing numerous doctors and not getting answers, Whitney was finally diagnosed with ME/CFS.

As his health worsened, he moved in with his parents in May 2011. He tried to keep working as a wedding photographer but soon gave that up because he needed a week to recover from shooting a single wedding. He soon became mostly bedridden.

In his last post on his photography website, Whitney lamented that “chronic fatigue syndrome” couldn’t do justice to his condition. He preferred “total body shutdown.”

Whitney has lost the ability to speak – something a very small fraction of ME/CFS patients experience. Dafoe says he used to communicate with the family via text messages, but that skill is now lost too, as even the glow of a smartphone screen is too much stimulation for him. The heart emojis he sent to his caregivers are just memories now.

Eventually he could no longer eat solid food.

In one of his last texts to his parents, he wrote, “I’m sorry I’m ruining your golden years.”

To seek a cure, Davis recruited a dream team of researchers

Over a life spent at the frontiers of science, Davis has collaborated with many accomplished researchers. He’s cashing in on those relationships now in building a world-class team he hopes can find the molecular basis for ME/CFS.

“I made phone calls, and everybody I called said yes,” Davis says.

Among those who picked up the phone were two Nobel Laureates: Paul Berg, who won the chemistry prize in 1980, and Mario R. Capecchi, who won it in the “Physiology or Medicine” category in 2007.

Some of his colleagues had never heard of the disease. He told them it affected 1% of the population, or about one in 300 Americans. He told them the National Institutes of Health at the time was dedicating less than $6 million annually to researching the disorder.

That poses a challenge in tackling an illness that lacks an FDA-approved treatment, doesn’t have a known cause or a singular lab test for clinicians to diagnose it. ME/CFS has lagged behind in the bio-medical imagination compared with cousins like multiple sclerosis, which also affects the immune system and the nervous system.

Following outbreaks in the 1980s, some dismissively called chronic fatigue syndrome the “yuppie flu.”

But its symptoms, which include constant exhaustion, pain, brain fog and unrefreshing sleep, can be as disabling as late-stage cancer. Taking a shower may leave someone with ME/CFS bed-bound and unable to do anything for days.

In 2017, NIH doubled its research spending on the disease to $12 million. But Davis argues that compared to other diseases of similar severity and prevalence, that’s not nearly enough. Multiple sclerosis, a disease that affects fewer patients than ME/CFS, attracts more than $100 million a year in NIH-funded research.

Davis now regularly convenes top scientists via an advisory board he set up through the Open Medicine Foundation, a California-based non-profit that’s raised $18 million to research the disease. Its hub is Davis’ Stanford Genome Technology Center, making Davis unique among living scientists in his ability to coordinate the discovery of a cure.

But to make the kind of progress he and his colleagues envision, they need a lot more money.

They are making slow but steady progress

ME/CFS patients, like those with multiple sclerosis and other diseases, fall on a spectrum. Some are still able to go to an office and work, while others are bedridden 23 or more hours a day.

At research conferences, Davis sometimes sits and talks with ME/CFS patients for hours.

“I’m very sympathetic to them,” he says. “It makes me feel that I have to solve this, but not in an arrogant way. I just know I have to put every ounce of energy into this to help all the patients, which also include my son.”

Davis and Dafoe know there’s a vibrant mind and spirit alive in their son’s weakened body. Whitney is a devout Buddhist, and their house is strewn with prayer flags. Dafoe thinks Whitney spends much of his day meditating.

When Whitney’s younger sister Ashley got married, Dafoe pointed to the ring on her finger to pantomime the happy news to her son. The two siblings had been very close. Whitney didn’t speak, but held his hands to his heart and wept with joy.

At Davis’ lab, Whitney’s blood samples are among many churning away in sequencing machines, contributing to what his organization believes is the deepest study of ME/CFS patients ever attempted.

This wouldn’t be the first time Davis has set his sights on a problem the scientific establishment found unsolvable. “You have to look for those,” he says.

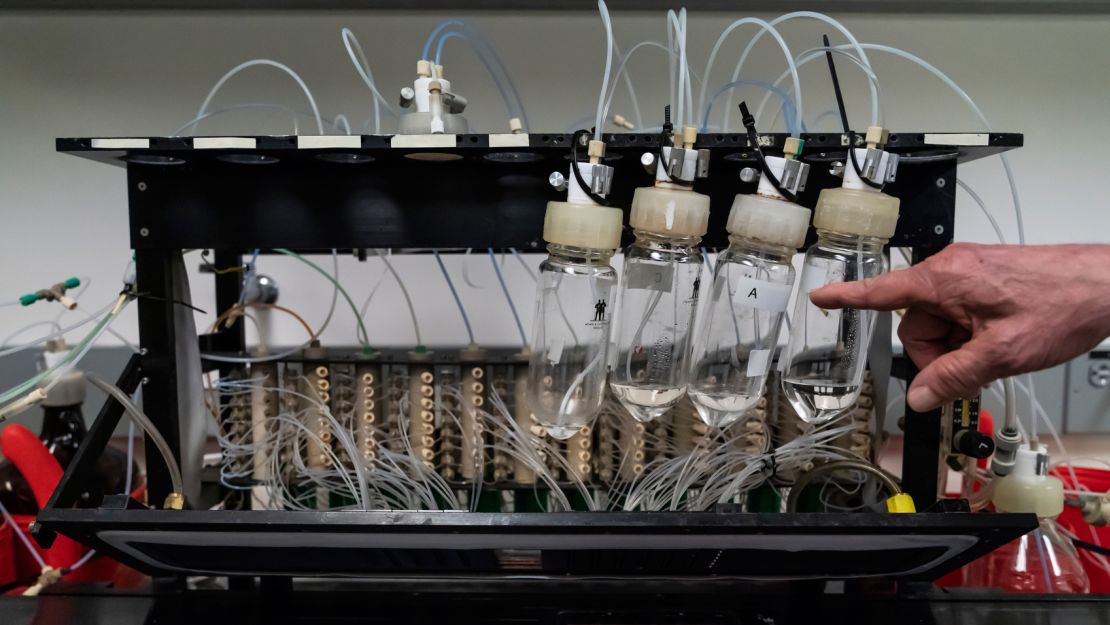

He and his team have been hard at work the past few years. One of their inventions, a “nanoneedle” for testing blood, speaks to the need to find a single biomarker in patients’ blood.

A blood test which identifies a specific molecular abnormality unique to ME/CFS patients has long been a sticking point in researchers’ quest to get the disease more recognized. Having one could spur more drug development, because pharmaceutical companies would understand the root of what’s wrong with patients.

Davis’ team has tested their nanoneedle with initial success and recently published their findings in a scholarly journal. They discovered ME/CFS patients’ blood responds to the introduction of “stress” – in this case, salt – differently than the blood of healthy people. Davis hopes the device will ultimately produce a cheap clinical test by which doctors can identify ME/CFS quickly and accurately.

He also wants to explore measures to prevent the disease. For example, he wants to understand why people with mononucleosis often develop ME/CFS.

Those are just a few of many things Davis’ team are working on.

“We don’t have enough money, so we have to prioritize,” he says.

Davis flew to Washington in early April for a symposium about ME/CFS. He almost didn’t make the trip because it would leave his wife at home alone, caring for Whitney while she had the flu.

But she told him he had to go.

Caring for Whitney is a daily ritual

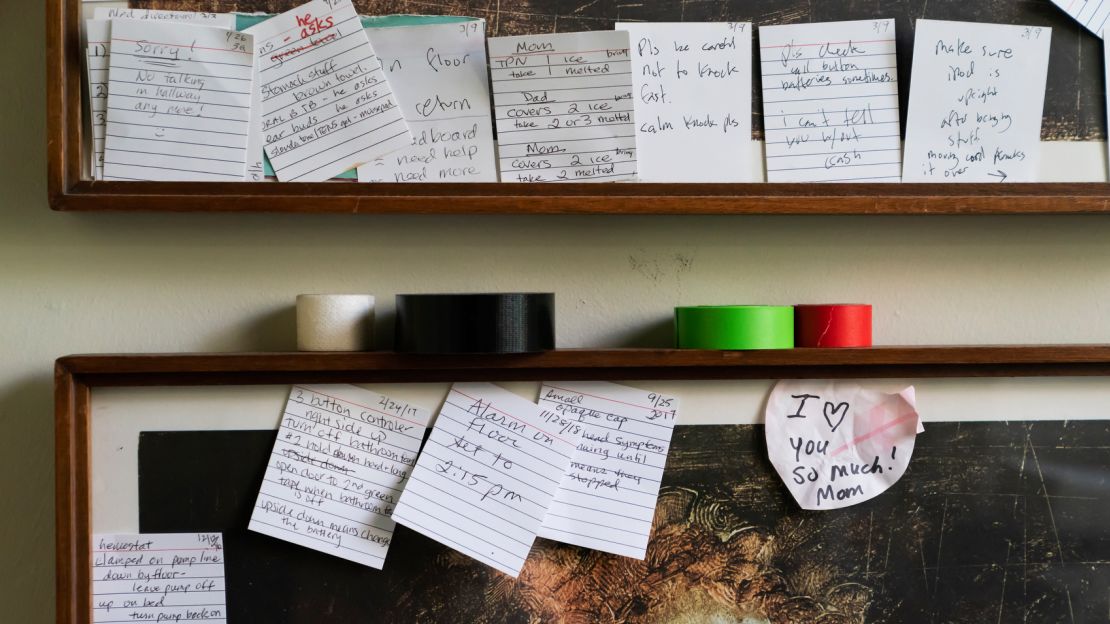

Davis and Dafoe sometimes wait for hours outside Whitney’s room, peering through a keyhole to see whether he has assumed a position in bed indicating it’s all right to come in. With words no longer an option, they must interpret Whitney’s postures and occasional hand signals.

Six times each day, every day, they perform this ritual, silently, dutifully, shut off from the gaze of the world.

They start around 2:30 p.m., first hooking up Whitney’s IV. On the next entry into his room, they hook up the pump for the “j-tube” that will send nutrients directly into their son’s stomach.

On the third visit, they wash and clean the small plastic vessels next to Whitney’s bed that he uses as urinals. Next they come back in to put the urinals on Whitney’s stomach for when he’s ready to use them again. On their last visit, often around 2:30 a.m., they’ll put ice on Whitney’s stomach to help soothe his excruciating digestive pains.

“I feel like I’m living in a different world. It’s hard to say anything when people ask ‘how are you doing?’” Dafoe says. “Our world has just been consumed by a chronic illness.”

There’s a disciplined intentionality behind their movements. For Whitney, the tiniest deviation in their procedure can be devastating.

“His cognitive processes don’t work right,” Dafoe says. She and her husband wear plain shirts with no lettering when they’re in Whitney’s room because the sliver of energy it takes his brain to process a word can cause him to crash. They even use tape to cover labels on tubes of Neosporin.

Such crashes cause Whitney severe stomach pain, which make it impossible for them to put more food in his feeding tube.

Dafoe wants her husband to get enough sleep so that he can stay fresh and focused on researching the disease. That means on many nights she’s up until 5 or 6 a.m. helping Whitney.

By 5 p.m. she’s back to caring for her son.

They hope their son’s suffering can have a greater purpose

“I got a PhD. That was hard,” Dafoe says. “I’ve climbed mountains. That was hard.”

But she says enduring Whitney’s illness is the most difficult thing she’s done in her life, “by a factor of thousands.”

One simple truth guides her. “He’s my son. I just love him.”

Dafoe receives messages from ME/CFS patients all over the world who say they are inspired by her husband and alarmed by her son’s severe condition. She says she feels like a mother to these people, many of whom are suicidal – a rational response to a life spent hovering just above death.

Many tell her Whitney is their north star. They say if he can go on living through hell, year after year, then their suffering must be endurable too.

“He’s saving lives,” Dafoe says. “Just by lying there.”

Nearly all her and her husband’s communication with Whitney is through pantomimed gestures. If he wants more of something he’ll hold his hands together, then bring them apart.

But every so often the fog lifts a little and Davis and Dafoe can speak more complex ideas aloud to Whitney. A few months ago, they told him how prominent his father has become in the field of scientists researching his disease.

“He was really excited about that,” Dafoe says.

Whitney punched the air like a boxer, signaling that he intends to fight on.

Ryan Prior is a cross-platform associate producer at CNN. He was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome in 2007 and wrote about that experience here.