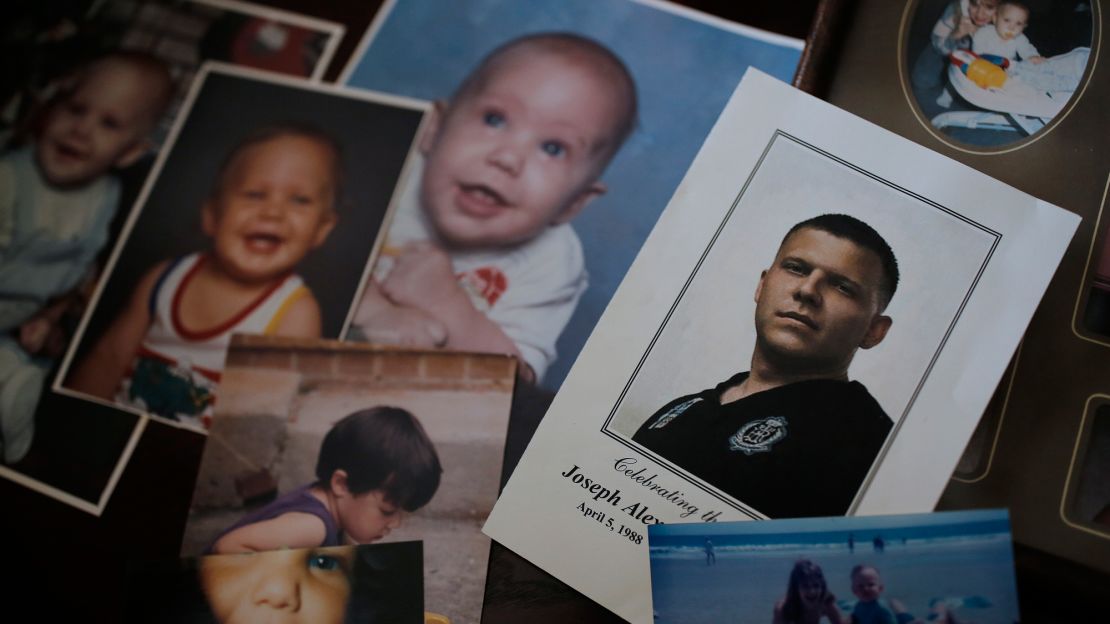

Jennifer Alba sifts through the boxes of photographs and documents. It’s a collection of what once was, and what her life has become. A mother sorting through pain.

There’s her son, Joseph, as an infant, smiling, dressed in a onesie with his bright blue eyes matching the blue backdrop. He was her firstborn, a gift who came into her life when she was just 17.

Not too far away lies the document from a middle school recommending that he be suspended for the last few weeks of school after being caught with marijuana. He was 13.

It was the start of a lifelong struggle with drug abuse that his mother desperately wanted him to break. Over the next 16 years, Alba says, her son spent dozens of nights in jails, cycled through nearly 20 stints in rehab and served two prison terms.

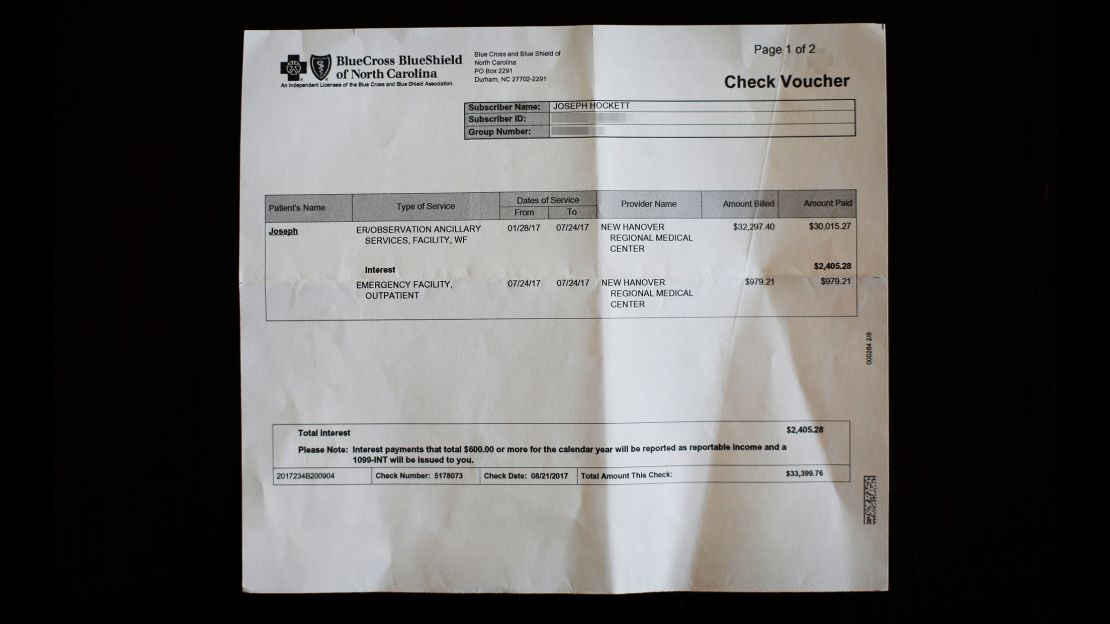

Alba pulls out a bank receipt for a deposit her son made in late August 2017. At 29, he was a DJ who played music at dive bars and strip joints. A good haul was 100 bucks a night. But this deposit was for more than $33,000.

She shakes her head.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina had sent her son a check for $33,399.76. It was for emergency care after he’d broken his jaw in a bar fight seven months earlier.

The check, which included $2,405.28 in interest, was more than he made in a year.

“Dirty money,” his mother says.

Over the next four days, her son made three cash withdrawals totaling $13,000. Alba has the receipts.

On September 2, 2017, the day after his last withdrawal, Joseph Hockett II was found dead.

Alba says her son had used the cash to go on the biggest binge of his life. Housekeepers found him in Room 135 of the Suburban Extended Stay of Wilmington.

A bottle of whiskey and a rolled-up dollar bill with white powder were found in the room, according to the autopsy report. The cause of death: cocaine and heroin toxicity.

‘A cloud of grief’

Alba reached out to CNN after reading a recent story detailing how Anthem and its Blue Cross entities send checks to patients for out-of-network care instead of reimbursing the providers directly.

Another woman told CNN that a family member received a check for more than $240,000 after out-of-network surgery. The practice has forced some providers to sue patients to recover the money.

Critics say it’s a tactic insurers use to pressure providers into joining their networks and accepting lower payments – one that puts patients in the middle of the fight by sending money straight to them.

The insurance industry says the policy is designed to protect patients from surprise bills and exorbitant charges from out-of-network doctors and hospitals.

For Alba, the story crystallized the questions she had after her son’s overdose.

It also compounded her grief: She had helped him sign up for insurance to avoid the tax penalty originally mandated by the Affordable Care Act.

“I didn’t realize insurance would be part of his death,” she says.

Alba says her son was the last person who should have received such a large amount of money. Her son’s life mattered, and she’s determined to let the powers that be know something must change.

“I’ve been in a cloud of grief for the last year and a half,” she says. “I’m angry at Blue Cross Blue Shield because they gave him money that wasn’t his … [and] it killed him.”

At the time, Alba had no idea about the Blue Cross check. It was only after police turned over his belongings and she went through them that she pieced together the money trail.

Among the items she says she found, in addition to the receipts for the $33,000 check and cash withdrawals for $7,000, $3,000 and $3,000:

? A PDF on his computer showing a $6,096.14 check voucher from Blue Cross in April 2017.

? A $14,104 check from Blue Cross in June 2017.

? A spreadsheet showing that Blue Cross owed him $73,400.01 for some three dozen medical services in 2017.

“They were sending the checks directly to him and not paying the hospitals,” his mother says, “which to me is absolutely absurd, and it’s careless, and it’s just ridiculous.”

Even after his death, the money kept coming. Nearly a year later, in June 2018, Blue Cross sent his estate a check for $2,496.95.

In all, Alba says, she is aware of at least $56,096.85 in checks from Blue Cross.

North Carolina insurance commissioner: This is ‘a real problem’

Making matters worse, Alba says, Blue Cross knew that her son had an addiction problem when it sent him the money. The June 2017 check for $14,104 arrived shortly after Hockett had checked out of rehab following a relapse. Alba also has Explanation of Benefits forms showing that Blue Cross covered at least one of Hockett’s visits to rehab in his final months.

Sending tens of thousands of dollars to a person with an addiction, she says, is “like dangling a piece of meat in front of a lion and telling him not to eat it.”

“Why would you give a person with mental health and addiction problems cash like that?” she asks. “It’s careless. It’s morally wrong. It’s horrible. I don’t know of any other way to put it.”

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina refused to answer questions about Hockett. The insurer also declined to discuss why it sent large checks to someone with addiction problems, whether checks have been sent to other people struggling with addiction, or whether anyone else has overdosed and died after receiving such sums.

“While we cannot comment on the specifics of a case due to privacy laws, we recognize this is a tragedy and extend our condolences to the family,” Blue Cross spokesman Austin Vevurka said.

Vevurka said the insurance giant tries to negotiate with out-of-network providers for urgent or emergency care on amounts over $25,000. But, he said, “if they refuse, we pay the member because that is who we are contractually obligated to pay.”

“We have applied this policy to numerous providers in the state and have typically successfully negotiated payments directly to the provider as a result,” he said.

That’s news to Cody Hand, a senior vice president with the North Carolina Healthcare Association, which represents more than 130 hospitals and health systems in the state.

Hand says he’s not aware of Blue Cross ever negotiating with any out-of-network providers on payments of more than $25,000.

Blue Cross sends the money straight to patients “so that they can force people into their network. They’re pretty blatant about that,” Hand said. Almost every other insurance company pays out-of-network providers directly, he said.

“Blue Cross is using the patients as a bargaining chip,” Hand said.

It’s a practice his association wants to see changed.

So does Mike Causey, North Carolina’s insurance commissioner.

“Generous insurance benefits and lump sum payments with few restrictions on out-of-network providers are a real problem that needs to be addressed by health insurers and legislators,” Causey said in a statement to CNN.

“The current system makes it way too easy for fraud to be committed and lives to be destroyed. The issue regarding how insurers use contract provisions to prohibit Assignment of Benefits is under review. Our goal is to establish guidelines that will protect the consumer while allowing insurers the ability to control health care costs. Our concern is provisions like these can be exploited and we are researching ways to address this issue.”

‘Can I be buried with grandma?’

Alba clutches her silver necklace, which is etched with her son’s name, his fingerprint and a heart.

A decorative wooden box containing some of her son’s ashes rests on a table in the front hallway, next to photographs of her boy over the years. The rest of his ashes is buried about an hour away.

His DJ turntable sits unused in the garage. “That was his passion,” she says. “It was one of the few things that brought him joy.”

Her son was an outgoing person with a warm heart and wry sense of humor, she says. Beyond his drug addiction, he struggled with suicidal thoughts and other mental health issues. He said that he hated being addicted and that if he ever overcame his addiction, he hoped to become a substance abuse counselor. She says he once recalled trying to help a young woman addicted to heroin.

“She’s not listening to me,” he told his mother. “You don’t understand how hard that is.”

“Yeah, I do,” his mom responded.

Realizing that truth, he broke down in tears.

Her son began spiraling in late January 2017, after he was blindsided at a Wilmington bar. He was there meeting friends when he was attacked. Someone punched him in his jaw, breaking it so badly that there was a 1-centimeter break on the lower right side, according to his medical records. Some of his front teeth were shattered.

A friend took Hockett to a nearby hospital, where he underwent multiple procedures, including having his jaw wired together due to the extensive break. The hospital wasn’t in his insurance network.

Hockett also was prescribed the powerful opioid oxycodone for his excruciating pain. He had always preferred a mix of cocaine, Xanax and alcohol, his mother says. Now, he was on to something much stronger.

On March 11, about six weeks after his jaw was broken, he woke up alone in a hotel room with a massive pool of blood on the floor and nightstand.

He had overdosed, and whatever he had taken had left him unable to recall events. He began texting his mom for help:

Three days later, Hockett was still struggling with memory loss and sent Alba a series of excruciating text messages:

Over the next three weeks, he would text about how he never wanted to use drugs again. That he wanted to start anew and make her proud.

But like so many who struggle with addiction, Hockett relapsed again, this time in early April. He checked back into a treatment center on April 8.

The ups and downs of recovery continued over the next few weeks. Anytime his mom began to think that her son had finally rounded the corner, a new text would arrive.

The next morning, he checked back into rehab.

For the next three months, he continued to struggle. In between, he sent texts of wanting a Shar-Pei, a type of dog known for its deep wrinkles and dark tongue. He talked about how big his two younger brothers were getting and spoke about wanting to cook a steak for his mother.

Her son would cook her that meal – a last supper she cherishes to this day. He swung by the house outside Raleigh and grilled steak for the family. They laughed and told tales. Then, he left the next morning for Wilmington, about two hours away on the North Carolina coast, where his girlfriend lived.

On August 31, 2017, at 10:53 p.m., he sent one more text to his mother. By then, he’d already deposited the $33,000 from Blue Cross and withdrawn at least $10,000.

“I love u mom,” he said.

She responded the next morning at 5:31 a.m.: “I love u.”

Joseph Hockett II would be found dead around midday the next afternoon, on September 2, 2017. Alba remembers looking out her front window. Three police officers were standing in the driveway, their heads hung.

She instantly knew.

A couple weeks later, when police returned her son’s possessions, she found the receipts and Blue Cross material in his backpack. She says she called Blue Cross, laid into them and really “let them have it.”

She was told a supervisor would call back. One never did, she says.

‘A punch in the heart’

The rectangular headstone reads:

JOSEPH ALEXANDER HOCKETT II

APRIL 5, 1988

SEPT. 2, 2017

LOVING SON & GRANDSON

His mother kept her promise to her son. Most of his ashes are buried with his grandmother Myra Thompson Long, who acted as a second mom in helping raise him.

“Seeing your child’s name on a gravestone,” Alba says, “it’s like a punch in the heart.”

Joining Alba at the cemetery is Jess D’Englere, who met Hockett in grade school and remained close with him throughout his life. She remembers him for “his smart mouth” but says he was “the warmest person.”

“He’d make you smile,” she says. “I’m really glad to be here for his mother.”

Steps from his grave, D’Englere says that the Blue Cross checks leave her baffled. After her own surgery four years ago, she says, she received a check from the insurer for more than $3,000 – an amount worth more than her car.

There was no explanation as to what the check was for or what she was supposed to do with it, D’Englere says. After speaking with several Blue Cross representatives, she says, she got this explanation: “It’s your money but not your money.” She ended up depositing the check and sending the funds to her provider.

“It was confusing,” she says. “It made no logical sense.”

The temptation to keep the cash, she says, was great. “What other emotion would you have?”

Imagine, she says, what it’s like for a person struggling with addiction, like Hockett, “when you see that type of money.”

The wind whips through the cemetery at the Shallow Ford Christian Church, providing a cold chill.

Alba fights back tears. “He shouldn’t have died that way,” she says. “It’s not the normal order of life.”

She and her son used to visit his grandmother’s grave to pray and honor her memory. “Now, they’re at peace together. It’s just odd seeing it,” she says. “But this is what he wanted.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

The sign in front of the church bears a fitting message: “What on Earth am I here for?”

Standing over her oldest son’s grave, Alba says she’s here to speak up for her son and make him “proud he’s not forgotten.”

“I couldn’t save him, but I’ll never stop talking about him,” she says. “Why else would we go through 16 years of hell? That is the reason.”

She repeats, “that’s the reason.”