Story highlights

Strikes are planned in almost 1700 towns and cities in over 100 countries

Youth activists tell CNN that adults are passing the burden of climate change to future generations

"We need to be listened to and we have no intention of giving up until our demands are met," a UK schoolgirl tells CNN

Adults have failed. Failed to slash emissions and failed to curb global warming – that is the view of hundreds of thousands of students who will protest climate inaction this Friday, by taking part in the Global Climate Strike.

Inspired by 16-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg’s weekly protests, the global youth climate movement has swept the globe, with students organizing strikes on every continent.

Meet 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg

Now, students are putting their collective voices together in a coordinated global school walkout, called Youth Strike 4 Climate. So far, strikes are planned in almost 1,700 towns and cities in over 100 different countries.

Five youth activists tell CNN about their motivations and hopes for the future.

Toby Thorpe, 17, Australia

“I’m very lucky to come from a place like this and that’s why I became an activist,” says Toby Thorpe.

Thorpe grew up in the Huon Valley in the far south of Tasmania. He is helping to organize the strike in Tasmania’s capital - Hobart - because he wants to ensure that future generations will experience the island’s natural beauty and clean air.

“The reality of climate change really impacted my community this year, when bushfires ravaged the Huon Valley, and burned over 200,000 hectares of wilderness across the state” he says.

In other parts of the country, floods and tropical storms are wreaking havoc. “These disasters are increasing in frequency and intensity, and all the science points to climate change,” says Thorpe.

A rallying point for Australian strikers is the plan to open a new coal mine in central Queensland.

The Australian government’s consent to the Carmichael mine, also known as the Adani mine after the Indian company developing it, has caused great controversy.

A Queensland government official told Reuters this week that Adani Enterprises might have to wait up to two years for environmental approvals to start construction.

“It’s outrageous. But we’re not going to sit and watch our futures being trashed because of their addiction to the fossil fuel industry,” says Thorpe.

Thorpe believes the government has not done enough to embrace new forms of clean energy.

“Australia is one of the sunniest and windiest countries in the world,” he says. “We have the money and the experts. We should transition to renewable energy right now.”

Just 6.7% of Australia’s energy comes from renewable sources, according to the International Energy Agency. Australia has set a target of increasing its renewable energy capacity to 51% by 2050.

Thorpe believes that most Australians back the striking students’ efforts. “No matter what your political beliefs, climate change is an issue that affects us all.”

Seo-gyung Kim, 17, South Korea

Seo-gyung Kim, a high school student in the South Korean capital, Seoul, came to climate change activism via nuclear power protests.

“My mom was a science teacher. She explained how nuclear power plants work when I was a primary student,” says Kim, adding that when she learned that water used to cool nuclear plants is returned to the ocean, Kim became concerned about marine pollution.

As a teenager, Kim began campaigning against nuclear power plants. In this capacity, she encountered Youth for Climate Action and joined the group as a volunteer to raise public awareness.

“I don’t understand why my government is not investing more in the renewable energy sector but is still investing in coal-powered plants,” she says.

Read more: The world’s most polluted cities

Just 2% of South Korea’s energy sector is currently renewable, the International Energy Agency tells CNN.

The country has vowed to close 14 coal power plants as part of its ’2050 Energy Vision Plan’, but recently invested tens of billions of US dollars in coal, according to the World Energy Council.

Air pollution is a serious problem in South Korea. The government declared it a “social disaster” this week and passed a set of bills to tackle the problem after seven cities experienced record-high concentrations of harmful PM 2.5 particles.

“When I step out of my apartment, I run into a seven-lane road,” says Kim. She says she can see dust and is conscious of the ultra-fine particles that clog the city’s atmosphere. “Nowadays, I feel breathing is more difficult,” she says.

Some positive steps have been taken, however.

Kim is pleased that the city of Seoul is equipping one million households with solar panels and that last year, a floating solar farm –the size of three football pitches and the largest in the country – was established.

Kim believes that South Koreans are not doing enough to tackle climate change because they assume it is a problem for the future – not for now.

“I don’t think adults are taking enough responsibility,” she says. “They are passing the burden to future generations.”

Shaama Sandooyea, 22, Mauritius

Shaama Sandooyea lives on a small island in the Indian Ocean, about 2,300 km (1,400 miles) off the coast of Africa.

She describes her home as a pocket of “yellow sandy beaches, turquoise lagoons and coconut trees, under a burning sun.”

Although it appears to tick all the boxes for a tropical paradise, Mauritius is in the grips of climate change.

The nation is especially vulnerable to rising sea levels and some people have lost their homes, while storm surges have devastated sections of coastline.

Although overall rainfall is decreasing, there are more heavy downfalls.

What is climate change? Your questions answered

In March 2013, a flash flood caused the death of 11 people in the island’s capital, Port Louis.

“Since that day, everyone is scared of rainfalls,” says Sandooyea. Meanwhile, the corals that once thrived offshore have “bleached extensively” due to rising temperatures over the last decade.

Sandooyea – who is studying for a degree in marine environmental sciences – credits her education for inspiring her activism.

In Mauritius, young people feel more worried about climate change than older generations because they learn about it in school and understand the threat, she says.

But despite the keen interest, there has never been a climate strike in Mauritius before and “nobody knew where to start.”

Sandooyea took the initiative: she contacted strike organizers in Europe for advice, set up a Facebook page and started spreading the word.

Sandooyea feels frustrated by political inaction and hopes to make an impact. “What is the purpose of education if … those who have the power to make a difference, are not listening to us?”

Scarlet Possnett, 15, United Kingdom

Climate change is “something that terrifies my generation”, Possnett says, expressing her frustration that as a teenager she cannot vote on climate-related issues “which we will have to deal with the rest of our lives.”

When the UK experienced its hottest February day on record this year, Possnett, who lives near Cambridge, says her immediate thought was “this is not how it should be!”

“It is impossible not to notice climate change,” she says.

Possnett says Thunberg’s weekly strikes outside the Swedish parliament made her realize “there is something students can do” to put pressure on their governments to take climate action.

She joined the UK Student Climate Network (UKSCN) in January and started organizing strikes across the country.

With other UKCSN activists, Possnett wrote an open letter calling on the UK government to declare a national climate emergency, to lower the voting age to 16 and include climate change in the national curriculum.

“I would much rather be at school [than striking] but I don’t have that luxury,” she says.

“We’re being heard, by politicians and the media, but that’s not enough. We need to be listened to and we have no intention of giving up on making noise until our demands are met,” she says.

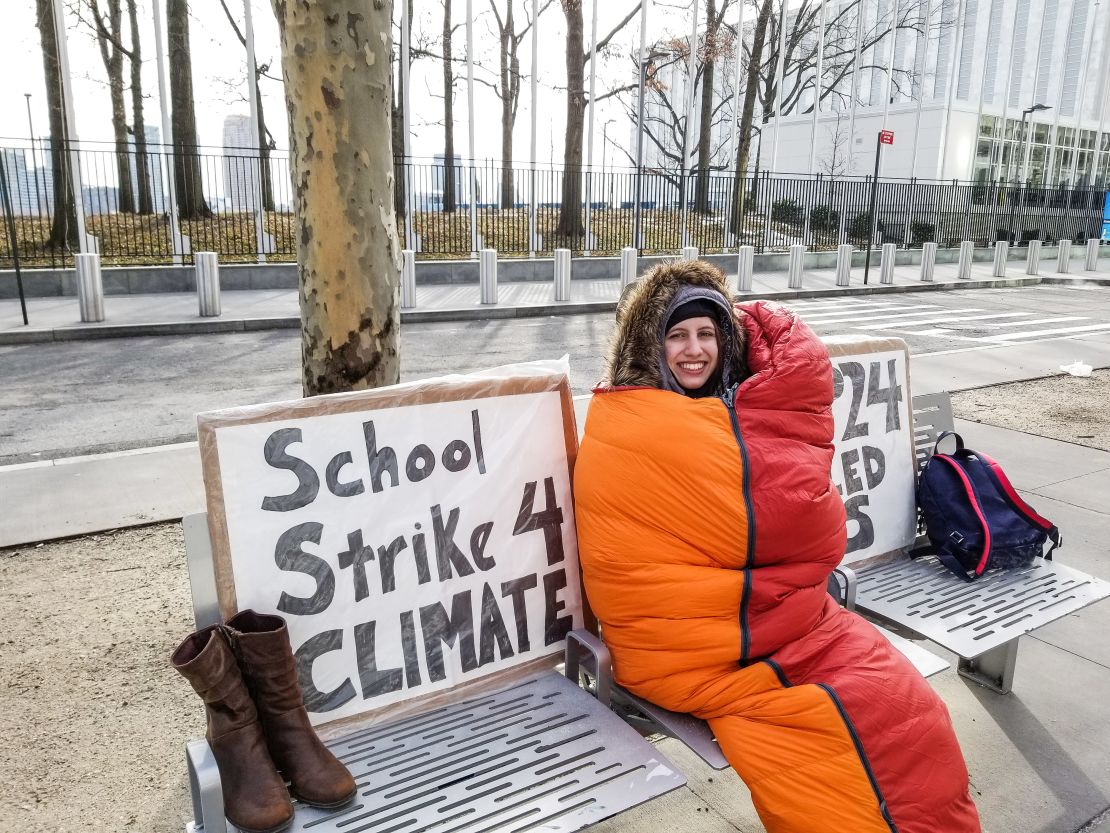

Alexandria Villasenor, 13, United States

When she was just eight years old, Alexandria Villasenor first became aware of the devastating impacts of climate change. A prolonged drought in 2013 caused the lake in her hometown Folsom, California, to completely dry up.

“I could walk across the lake and saw dead fish. It was a scary experience,” recalls Villasenor, who now lives in New York City.

Villasenor was once again confronted by the threat of climate change when mass wildfires broke out in Paradise, California, last summer. She was visiting family nearby but had to leave because she was struggling to breathe because of the smoke.

“I started to realize [these events] aren’t normal and that they are linked to climate change,” she says.

Villasenor’s experiences of climate change and Thunberg’s rousing speech at the United Nations climate summit inspired her to become an activist.

Every Friday, Villasenor strikes against global climate inaction outside the United Nations headquarters. “I sit there until I’m numb. I’ve even striked in the polar vortex,” she says.

She has been striking for 14 weeks now and helped organize strikes across the United States.

“I’m upset with how world leaders are treating the climate crisis. [The youth] need to make sure that people in power start taking action because we don’t have time to wait until we can,” she says.

Curbing global warming is possible, but only if governments take “drastic change now,” Villasenor says. “We need to cut emissions by 50% by 2030, stop fracking and stop coal mines,” she adds.

She hopes that the youth climate strikes “will achieve more action from world leaders,” pointing to the success of campaigners in Germany, who lobbied the government to phase out coal by 2038.