Editor’s Note: Peniel Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of several books, most recently “Stokely: A Life.” The views expressed here are his. View more opinion articles on CNN.

The end of February also marked the end of an utterly bizarre Black History Month. It brought us what for many was a long-awaited conversation addressing the ways in which America’s discussion of racial injustice has regressed by decades. In a country where Barack Obama was President, public discourse is still dominated by enduring, pernicious tropes such as blackface, cotton, and “some of my best friends are black.” Notably, the blackface and cotton episodes occurred in the same state, and featured the same couple: a month that began with Virginia governor Ralph Northam facing calls for his resignation after he admitted to dressing up in blackface ended with his wife Pam under fire for handing cotton to a group of black and white children on a tour of the governor’s mansion and, according to the mother of a black child in the group, asking them to imagine being slaves in the fields.

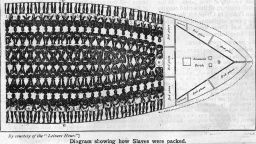

Black History 2019 contained plot twists that wove together politics, culture, law enforcement and more into a dizzying national reckoning: politicians in blackface, a white actor who confessed to murderous racist impulses, a black actor who seemingly faked his own hate crime, films about race touching off a firestorm at the Oscars and white fragility about confronting racism unfolding in real-time in the House of Representatives during the Michael Cohen hearing. All of this, implausibly but inexorably, managed to overwhelm the staggering fact that this year represents 400 years since Jamestown, Virginia introduced slavery to colonial North America.

It also managed to overshadow the settlement between Colin Kaepernick and the NFL, a monumental victory for the former quarterback who set the world ablaze by simply taking a knee during the national anthem in protest against police violence against black Americans.

Liam Neeson’s awkward confession about his failed efforts to hunt, capture, and kill a random black man after his white friend’s sexual assault set the stage for an at-times candid discussion about the roots of anti-black racism. Neeson’s openness, while pilloried in some quarters, represents a refreshing departure from the clichéd responses by most whites in the public eye that they are absolutely “not racist!” While Neeson defensively proclaimed the same under intense scrutiny, we are left with hints about the merits of courageous conversations about race, ones where people can admit to racial prejudice – past or present – in hopes of bridging political and cultural divides.

Jussie Smollett’s apparent faking of a hate crime in Chicago dominated black Twitter and national news for large chunks of Black History Month. If Smollett – brilliant, openly gay and charismatic – began the month standing in a long line of black heroes who faced physical violence just for breathing in their own skin – by the end he became a cautionary tale, accused of irrevocably damaging future real victims of racial and homophobic violence and hate.

Chicago Police Superintendent Eddie T. Johnson, who is black, and Mayor Rahm Emanuel immediately castigated Smollett as the literal bête noir of every white American who has ever feared, from the days of antebellum slavery to the present, that blacks unscrupulously make up allegations of racial discrimination from thin air.

Chicago’s mayor and police superintendent deployed the “race card,” but the punch line to their righteous indignation in the Smollett case is Chicago’s history of systematic police abuse and cover-ups of physical violence, brutality, and even death of black folks at the hands of the police.

If real life during Black History Month took on strange new dimensions, cinematic depictions celebrated at the Academy Awards showed the best and worst of where America stands in its efforts to grapple with its own racial past. We saw both the honoring of complexity and nuance and the lionizing of unearned racial reconciliation.

Black folk were so conspicuous at the 2019 Oscars that one might almost forget the recent stinging #OscarsSoWhite campaign that helped usher new and more diverse members into the Academy. That campaign paid off handsomely in the best picture nominations of Black Panther, a futuristic vision of unapologetic black excellence that smashed box office records and myths about commercial viability for black movies, and BlacKKKlansman, which riffed on both the political climate of the Black Power era and the post-Charlottesville contemporary moment.

BlacKKKlansman’s ending, which featured real life footage of the 2017 white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, deftly connected the past to the present by illustrating that racial hatreds once thought relegated to history’s dustbin remain frighteningly alive in the present.

Spike Lee’s long overdue Oscar, for best-adapted screenplay, seemed particularly appropriate. Lee, still the cinematic enfant terrible whose masterpiece “Do The Right Thing” set my 16-year-old heart aflame during the summer of 1989, gave a poignantly stirring acceptance speech dressed in full purple regalia in homage to the late artist Prince.

But then “Green Book” won the Oscar for best picture.

“Green Book,” a film based on the real-life relationship between a gay black concert pianist and his Italian-American chauffeur, is at once astonishing and to be expected. Denounced by the family of Don Shirley, the late pianist, “Green Book” casts a familiar cinematic spell by examining racial discrimination on a black man – through the eyes of a white man who comes to be his friend. Critics have called it a reverse Driving Miss Daisy, the Morgan Freeman-Jessica Tandy film that won the Best Picture in 1990 for its white-palatable version of interracial friendship, and accused it of being the worst Best Picture winner in 10 years – since the elevation of “Crash,” a melodramatic rehearsal of our worst racial stereotypes. To put a final point on it, “Green Book’s” producer singled out white actor Viggo Mortensen in his acceptance speech, saying “it started with Viggo” – instead of acknowledging Shirley or Victor Hugo Green, who created the Green Book from which the film takes its title (a yearly guidebook for African-Americans to safely navigate the segregated south on road trips).

Just as the “my black friend” trope was winning statues, it also took center stage during Michael Cohen’s testimony before the House Oversight Committee. Cohen gave a first-hand account of President Donald Trump’s anti-black racism – and his candor represented a step toward progress. Cohen’s accusation that the President is “a racist,” coming on the next to last day of February, seemed a fitting end to Black History Month, a time that reminds all of us to form a better understanding of the gap between the promise of equal citizenship and its reality.

Then Rep. Mark Meadows stepped in and took us all back to the Jim Crow era by defending the President against charges of racism by pointing to the presence of Lynne Patton, a black event planner turned Housing and Urban Development official, as definitive proof that Trump does not hate black people. The “black friend,” a trope as old as the history of racial slavery in North America, stood resuscitated on a national stage for the 21st century. Only Donald Trump (with an assist from Meadows, who, though he now says he no longer supports these remarks, in 2012 was caught on video vowing to send then-President Barack Obama “home to Kenya”), who once spoke of legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass as if he were still alive, could surpass the sepia-toned mythology of racial relations in “Green Book” with a more shameless effort at purchasing racial justice on the cheap.

When called out by Rep. Rashida Tlaib for his actions, Meadows wrapped himself in the cloak of white fragility, forcing his own black friend, Rep. Elijah Cummings, to testify to Meadows’ moral standing and mediate Meadows’ pain before the cameras – rather than acknowledging what he’d done.

Black History Month 2019 closes, then, with America off balance when it comes to race, in the middle of multiple conversations about courage and discomfort about racial injustice. This year’s jaw-dropping Black History Month essentially tells the story of America, the complex and damaged underpinnings of our democracy.

I’m taking away from Black History month the image of Spike Lee preaching to the nation about the significance of 1619. My hope is that he will rouse future generations, who will ask more difficult questions on the road to more courageous conversations about racial justice and black citizenship.