Story highlights

The US obesity rate for youth, aged 10 to 17, was 15.8% in 2016 to 2017, new report says

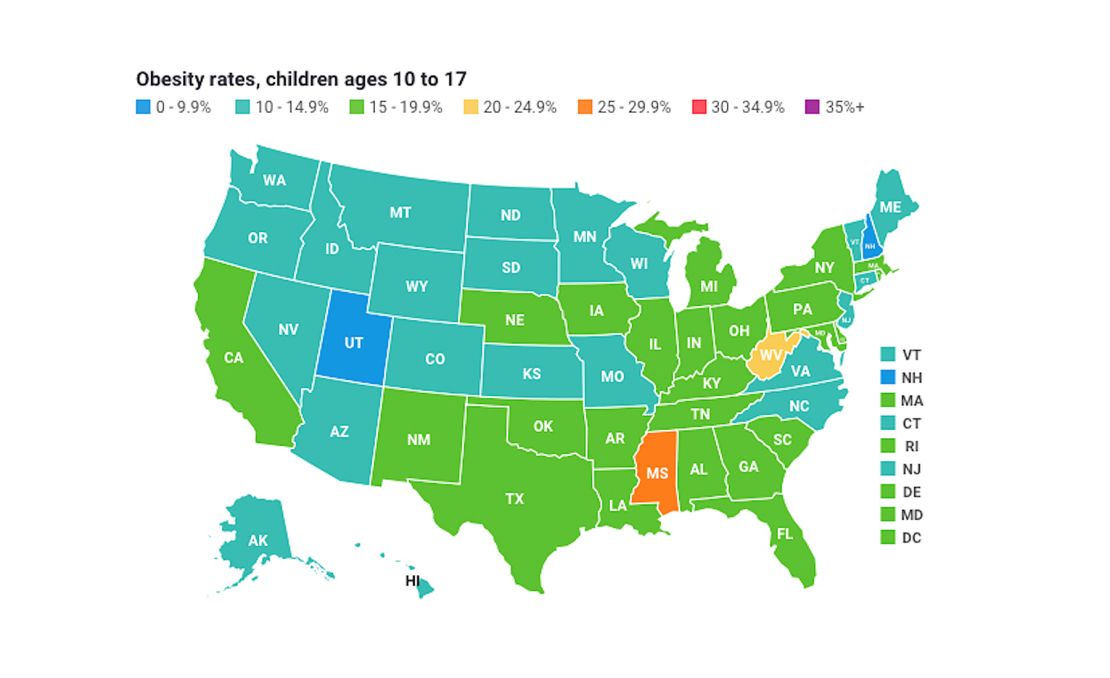

Mississippi had the highest childhood obesity rate at 26.1% for that time

Utah had the lowest at 8.7%

Childhood obesity has long been a problem in the United States.

Now new research from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation reveals new state-by-state differences and just how serious the problem has become.

The research brief, which was released on Wednesday, shows that the national obesity rate for children, aged 10 to 17, was 15.8% in combined data from 2016 and 2017, similar to the 16.1% rate found in 2016 data alone.

“We know childhood obesity continues to be a major challenge, a public health crisis in this country, and one that has many significant health and financial impacts,” said Jamie Bussel, a senior program officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in New Jersey, who worked on the report.

“Roughly one in three young people nationally is overweight or obese and I think the new data we’re releasing are a real stark reminder of that fact,” she said. The data “should really urge all of us to think about the kinds of changes that we need to be making that will help all kids grow up at a healthy weight.”

Obesity, which means having too much body fat, can increase the risk of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and even some cancers.

In the US, the percentage of children and teens affected by obesity has more than tripled since the 1970s, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In the United Kingdom, obesity is a common problem estimated to affect around one in every five children aged 10 to 11.

Obesity also has become a global issue. Worldwide, the number of overweight or obese infants and young children, up to 5 years old, climbed from 32 to 41 million between 1990 and 2016, according to the World Health Organization.

The current state of childhood obesity in America

The new research brief involved analyzing national health data on children in all 50 states and the District of Columbia who are up to 17 years old. The data came from the 2016 and 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health, which sampled 364,150 and 170,726 households nationwide respectively.

In the surveys, parents or caregivers provided their children’s height and weight, which was used to calculate body-mass index, which then could determine childhood overweight and obesity for the brief.

The combined 2016 and 2017 data revealed that Mississippi’s rate of 26.1% was the highest state rate above the national rate of 15.8%.

Mississippi was the only state that had a rate statistically significantly higher than the national average, the researchers noted in the brief. Other states with rates that were higher, but not statistically significantly, were:

- Alabama at 18.2%

- DC at 16.1%

- Delaware at 16.7%

- Florida at 16.9%

- Georgia at 18.4%

- Iowa at 17.7%

- Illinois at 16.2%

- Indiana at 17.5%

- Kentucky at 19.3%

- Louisiana at 19.1%

- Michigan at 17.3%

- Ohio at 18.6%

- Oklahoma at 18.7%

- Pennsylvania at 16.8%

- Rhode Island at 16.8%

- Texas at 18.5%

- West Virginia at 20.3%

Whereas, eight states – Colorado at 10.7%, Connecticut at 11.9%, Minnesota at 10.4%, New Hampshire at 9.8%, Oregon at 11.4%, Utah at 8.7%, Washington at 10.1%, and Wyoming at 10.6% – had rates significantly lower than the national rate, the combined data showed.

When comparing its 2016 rate alone with its combined 2016 and 2017 rate, “one state that stands out this year is North Dakota, which saw its obesity rate go down,” Bussel said. “This is really encouraging.”

In 2016, North Dakota had a rate of 15.8%, which dropped to 12.5% in the combined data, according to the research brief.

The data also showed significant differences in national rates by race and ethnicity.

“From the national perspective, over 22% of black youth have obesity and that’s actually compared to over 20% of Hispanic youth and over 12% of their white counterparts,” Bussel said. The rate was 6.4% among Asian youth and 16.3% among youth of multiple races.

“So I think the persistency in the disparities in rates is an incredibly troubling factor that we as a nation need to be addressing and really focusing on,” she said.

The study had some limitations, including that the height and weight data were self-reported from parents, so subject to possible bias. Also, the data only showed rates for 2016 and 2017. More research is needed to determine rates from previous years in order to track and determine trends over time.

The brief included recommendations, from this year’s State of Obesity report, for preventing obesity and promoting a healthy weight among children nationwide. Some of the recommendations were:

- Congress and the current administration should maintain and strengthen nutrition supports for low-income families.

- The US Department of Agriculture should maintain nutrition standards for school meals that were in effect prior to changes made last year.

- States should ensure that all students receive at least an hour of physical education or activity during each school day.

- Food and beverage companies should eliminate children’s exposure to advertising and marketing of unhealthy products

What’s driving state-by-state differences

The new report provides a “succinct” and “clear” snapshot of the current state of childhood obesity in the US, said Marlene Schwartz, a professor and director for the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity at the University of Connecticut, who was not involved in the report.

She added that several factors could be driving the state-by-state differences seen in the research.

“I think that part of it may be economic – states with higher levels of poverty may have higher rates of obesity. That can be traced back to the fact that it’s difficult to eat a healthy diet with limited income. The researchers also found that overall, there are different rates of obesity by race and ethnicity. So, another explanation for differences across states may be the variability in demographic profiles in states across the country,” Schwartz said.

“I live in Connecticut and I know that Connecticut is on average a higher income state. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that on average we also have lower rates of childhood obesity,” she said. “Until there are larger shifts in our food system to make it more affordable for families to buy healthier foods, this will continue to be a challenge.”

‘This is a true national crisis’

All in all, the new research brief confirms what has been seen for decades: that childhood obesity is a national epidemic and it could have serious implications for the future of public health, said Dr. David Ludwig, a professor at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, who was not involved in the study.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Ludwig and several coauthors published a 2005 report in The New England Journal of Medicine that predicted a significant shortening of life expectancy in the US by mid-century due to the effect of obesity on longevity.

Now, “that prediction seems to have come to pass many years sooner than expected. In 2015 and in 2016, life expectancy decreased for the first time since the Civil War in the United States. Many factors were likely involved – including the opioid epidemic – but obesity-related diseases were an important contributor,” Ludwig said.

The first generation born in the obesity epidemic is just reaching middle age. They’re going to be developing life-threatening complications – diabetes, heart disease, fatty liver – at much higher rates than was ever before the case. This has and will continue to place an enormous strain on the health care system, cost hundreds of billions of dollars to the economy, and extract a tremendous human toll of suffering and shortened healthy lifespan,” he said. “This is a true national crisis.”