The teenagers drop down on their stomachs, slap the floor with their hands and rise with a gracious twirl. They then proceed to flap their arms like a flock of birds to the beat of a K-pop song.

There are at least 50 of them, crowded into a low-ceilinged room with mirrors on three walls. It is hot, it is sweaty and it is 9.30 p.m. on a Wednesday night.

The group, who have been practicing the same move repeatedly for nearly two hours straight, are all students of Def Dance, an elite dancing and singing school in Seoul’s upscale Gangnam neighborhood.

“I spend about three hours here every day after school,” says Lee Jae-Gi, a skinny 16-year-old wearing a gray sweatshirt. I started taking classes when I was 11.”

He studies K-pop, hip-hop and singing. “Practicing the same move over and over again can be tiring but I am progressing and that is all I care about,” he adds.

The teenagers enrolled in Def Dance are all single-mindedly pursuing the same aim: to become a K-pop idol. Becoming one of the chosen few guarantees fame, success and a bank balance that sets them up for life.

But the school, which charges $200 per month and has 1,400 students, some as young as eight, is only the first rung on the ladder to fame.

To become a true idol, teenagers like Lee must first make it through ultra-competitive auditions held by the record labels. Those who are chosen become “trainees.” They will be expected to give up their freedom to live and train for several years at one of Korea’s elite K-pop academies. Only then will they get a shot at stardom.

There are dozens of schools helping to prep kids for these auditions across Seoul, each charging anything up to $1,000 per semester.

Life as a trainee

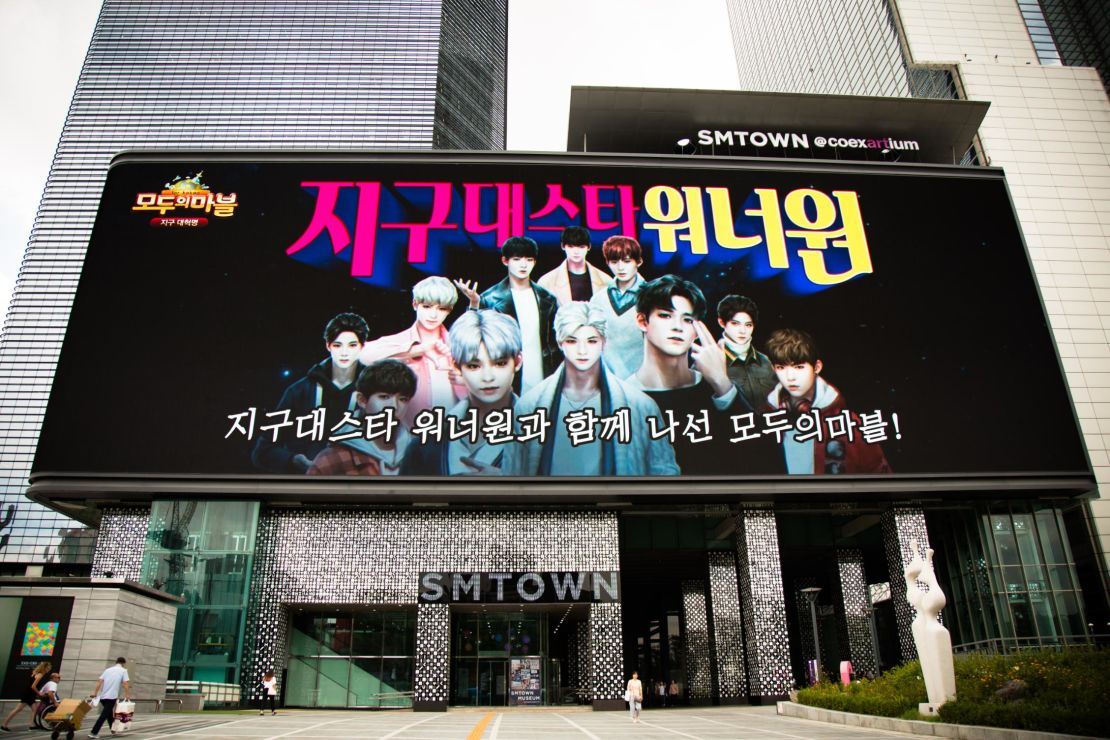

Three record labels dominate the K-pop industry, which generated $4.7 billion dollars in 2016, SM Entertainment, JYP Entertainment and YG Entertainment. All were formed in the late 1990s, when K-pop first started to take off.

Their trainee selection process is incredibly competitive. “We hold 500,000 auditions a year,” explains Choi Jinyoung, who is setting up a new academy for SM Entertainment. “Less than 10 people get chosen every year to become trainees.”

Personality and a “good character,” which means being hard-working and disciplined, are the key elements recruiters look for.

Dedication though is no guarantee of success. “Knowing how to dance and sing are not so important,” details Patty Ahn, an expert on contemporary Korean culture at the University of California, San Diego. “That can be taught.”

Looks – a crucial element of the K-pop universe, which churns out about 20 new bands every year with perfect faces and figures – can also be arranged. Most idols have had some form of plastic surgery, says Ahn.

Academy trainees are usually aged between 10 and 14 and spend two to three years following a grueling full-time training schedule, modeled on Korea’s military service.

Close to the country’s border with North Korea is the Global K Academy.

The academy is set amid a housing development modeled on a small English town near the city of Paju in Gyeonggi Province. There is a pub, statues of Buckingham Palace guards, and a cafeteria covered in dark wood paneling that makes it look like an Asian Hogwarts.

“Trainees spend one year with us,” says Penny Park, the school’s marketing manager. “They learn how to sing, dance, do their make-up, pose in front of a camera and speak in public.” During their training, the future idols live in dorms. The academy has lodging for up to 800 students.

“They only go home once every three months,” says Park. Crayon drawings on the walls and a pile of board games stacked on a table are a reminder that the trainees are barely in their teens.

The students also take drama lessons. “It teaches them how to use their voices and facial expressions,” explains Aurore Barniaud, who works at Global K where she helps to oversee the trainees’ development.

She points to a long narrow room, with mirrors on all of the walls. “Here, they train their walking and posture, to prepare for the stage,” she says. There is also a recording studio and a concert hall.

Daily life for the trainees at the academy is tough.

During the first few months of their training, she says she finds them in tears most evenings. There is no privacy for the trainees. They sleep, eat and train together. Their mobile phones are confiscated.

“The girls are weighed every day and we monitor everything they eat,” explains Barniaud. “On days when they have TV appearances, they only get one meal, because being on camera makes you look fatter.”

Making the grade

The lucky few that get through the training are assembled into bands of 4 to 12 members. Their official debut is usually an appearance on a music show, during which they play their first single and present themselves to the public.

After they have debuted, most K-pop stars have to sign what are often dubbed “slave contracts.” These can run for as several years and provide them with only a tiny share of the potentially massive revenue they generate in record sales and concerts.

Training an idol costs an estimated $100,000?per year and the studios want to recoup their investment. Only when the stars have paid off all their debts will they begin to make better money.

Their private lives are also closely monitored: relationships, alcohol and drugs are all prohibited. In September, Cube Entertainment, a K-pop label, fired two of its stars, Hyu Ah and E’Dawn, because they were dating.

In one of Global K’s classrooms, a group of girls is dancing to the tune of Twice’s “Dance the Night Away.” The teacher shows them the moves and helps them position their arms. And off they go, stomping their feet, swinging their arms high in the air, a permanent smile plastered on their faces.

They have all come from Taiwan to take part in one of the academy’s specially designed intensive training courses. This morning, they spent several hours singing a Shawn Mendes number. Tomorrow, they will audition in front of South Korean music execs.

“I wanted to see if I have enough talent to become a trainee,” says Amber Tseng, a self-assured 14-year old with a strong voice. Yang Fang Chi, a petite 17-year old with a bob, hoped to improve her dancing. “My aim is to move to South Korea and become an idol,” she announces.

Unfortunately, the following day, none of the Taiwanese students make it past the audition. “None of them really stood out,” sighs Bora Kim, the dance teacher.

After taking over South Korea, K-pop is now conquering the rest of the world.

“It spread to the rest of Asia, especially to Japan, China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, at the turn of the century, fueled by the export of South Korean TV shows,” explains Michelle Cho, who studies K-pop at Canada’s McGill University.

After 2008, it started gaining popularity in the United States and Europe, thanks to YouTube.

Recording studios have started actively promoting K-pop abroad. China, with its gigantic audience, looks especially promising. Many bands are translating songs into Japanese, Mandarin and English.

Some split into subgroups, each one touring a different linguistic area. The new trend is to create super-groups made up of different nationalities.

Global K has embraced it wholeheartedly. “The Korean market is saturated so we are now focusing on recruiting Chinese, Taiwanese and Hong Konguese trainees,” says Park.

In 2017, the academy debuted a band called Varsity, with Korean, Chinese, American and Emirati members. It has also held a series of auditions in Myanmar and hosted a reality TV show to create a half Japanese, half Korean band called Iz One. It will debut on October 29.

If the South Korean experience is anything to go by, there won’t be a shortage of young would-be stars ready to offer themselves up for hours of training and endless scrutiny.

For many, it’s all or nothing.

“This is one of the biggest problems in the industry,” says Park, the marketing manager. “Since they often stop school to pursue a musical career, there is not much out there for them if it doesn’t work out.”