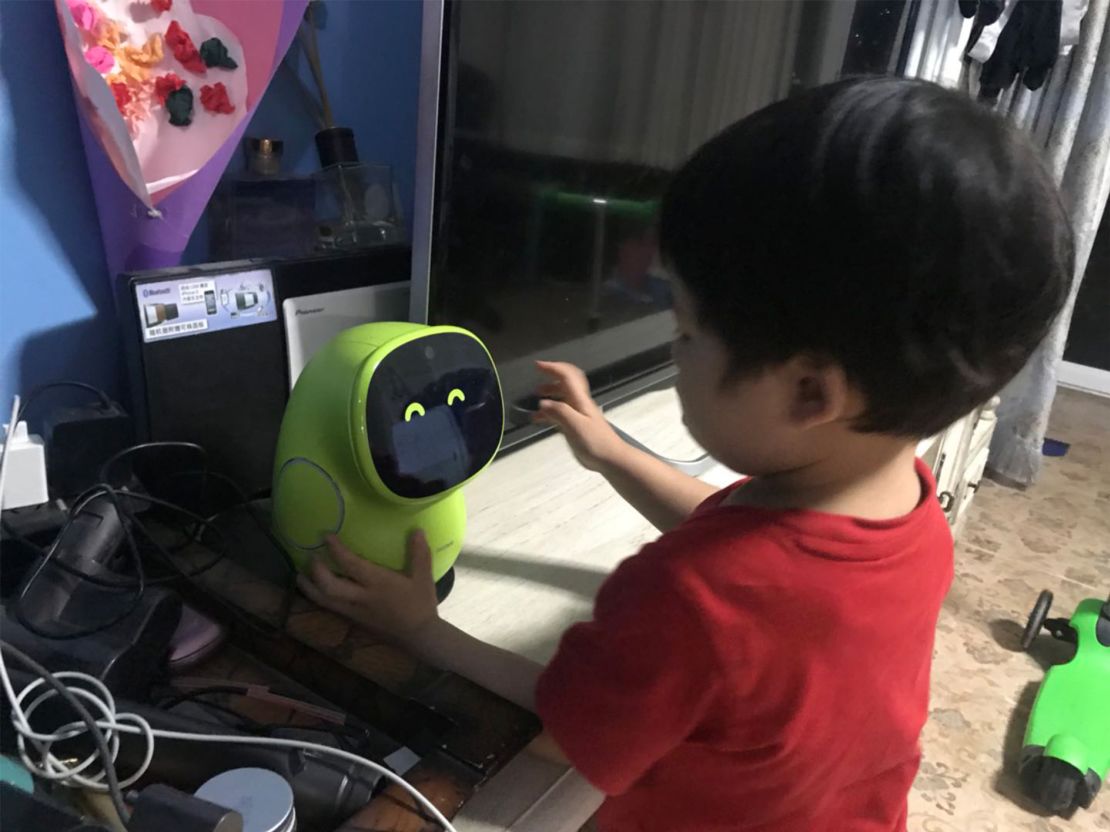

At kindergarten, three-year-old Seven Kong has his schoolmates to play with, but at home his best friend is a kidney-shaped, lime-coloured android named BeanQ.

The two spend hours together, with Seven peppering the robot with a continuous stream of questions.

“What’s up BeanQ? Have you eaten? I wanna watch cartoons!”

The green android responds with similarly simple words and phrases, alongside an array of different emoji facial expressions displayed on a large screen, which serves as its face.

Recommended to the family by a friend, the android is intended to be an early educator, sharing some of the parental burden.

“When we get really busy, BeanQ can be there keeping him entertained,” said Seven’s mother Liu Qian, 33, who is a work-at-home mom living in Beijing.

Despite occasional glitches in voice recognition, Liu said the machine doesn’t have any problems interacting with the active three-year-old.

Driven by a cluster of leading AI companies and using ad campaigns that target tech-savvy parents, early education products have taken a futuristic turn in China, where the popularity of such devices has boomed.

A search on Tmall (China’s equivalent to Amazon) with “education robot” gives 65 pages of products.

Parents say the benefits of AI gadgets extend beyond the realm of education. BeanQ, for example, also features a “remote babysitting” mode, under which it can serve as a moveable nanny, automatically taking snaps of children and uploading them online for parents to see.

Yuan Wen, a 32-year-old mom, said that she uses this function a lot to capture her son’s pivotal moments as he grows up as well as to communicate with him while away.

“With BeanQ, I can video chat with my son when I need to work late,” she said.

But some experts have questioned the value of the AI education devices, dismissing them as little more than a “low-end smart phone” for overworked parents.

Others have raised darker concerns around privacy and child safety, worried that parents are putting unsecured visual and location data about the children online.

Childcare for the masses

With a price tag of just $300, BeanQ has quietly made its way into millions of ordinary middle class households across China.

“In this industry, within three to five years, every toy will go digital. There will be no inanimate toys anymore,” James Yin, president of Roobo, the manufacturer behind BeanQ told CNN.

“Children get bored at toys easily, no matter how fancy they are. But AI is living, and ever changing,” he said.

Roobo is just one of a group of Chinese AI companies that use the concept of early child education to commercialize their technology.

“(Robots for children) is the sector where AI can take off in its earliest stages,” Yin said. He thinks that children are less picky about the level of intelligence of their robots as long as the toys look animated and interact with them.

Roobo recently developed an AI system that incorporates a range of English-language learning materials. It’s an area the company say is set to boom, as parents look to create native English-speaking environments, without the hassle of traveling abroad.

Booming market

If digital watches for children are included, an estimated 30 million AI educational robots were sold in China this year, and next year the number is expected to exceed 100 million, according to research carried out by Turing Robotics, a major AI toy solution supplier in China.

Turing is among a number of companies that are developing products that can be used outside the homes in schools and hospitals.

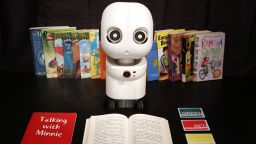

Turing recently partnered with tech companies Sharp and Foxxconn to develop RoBoHoN, an AI robot phone.

RoBoHon goes beyond simply taking voice demands and regurgitating encyclopedia entries, said Guo Jia, COO of the company.

“It has emotions. It’s playful, headstrong and mischievous,” he said. “It initiates talks and shifts the topic in conversations. It has the ability to learn.”

The $2,000 RoBoHon has been used in Harbin Children’s Hospital for children with autism.

Li Huaining, deputy dean of the hospital explained that RoBoHoN is more tolerant than most humans of the hyperactivity and repetition shown by many children with autism.

‘Misleading for consumers’

The demand for high-tech robot gadgets has led to a proliferation of products claiming to have AI functionality.

According to Christian Grewell, Professor of Interactive Media Arts and Business, NYU Shanghai, anything that implements some type of machine learning algorithm can be called an AI device.

“Most of the educational robots I’ve seen for sale commercially here (in China) are closer to a low-end smart phone, but without the benefit of a diverse app store,” he said.

While AI toys might appear to make parent’s lives simpler, they also carry a degree of risk, with many exerts calling attention to the trove of personal information typically stored on devices.

BeanQ, like many other popular AI toys on the market, builds up a detailed profile of a child through hours of daily interactions, allowing parents to analyze their child’s development.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“What I worry most about is the low-end market, where the producers are more focused on a quick buck and not on the security of the device,” said Grewell.

“The investment (for parents) might be better spent on a tablet that can perform the same functions.”