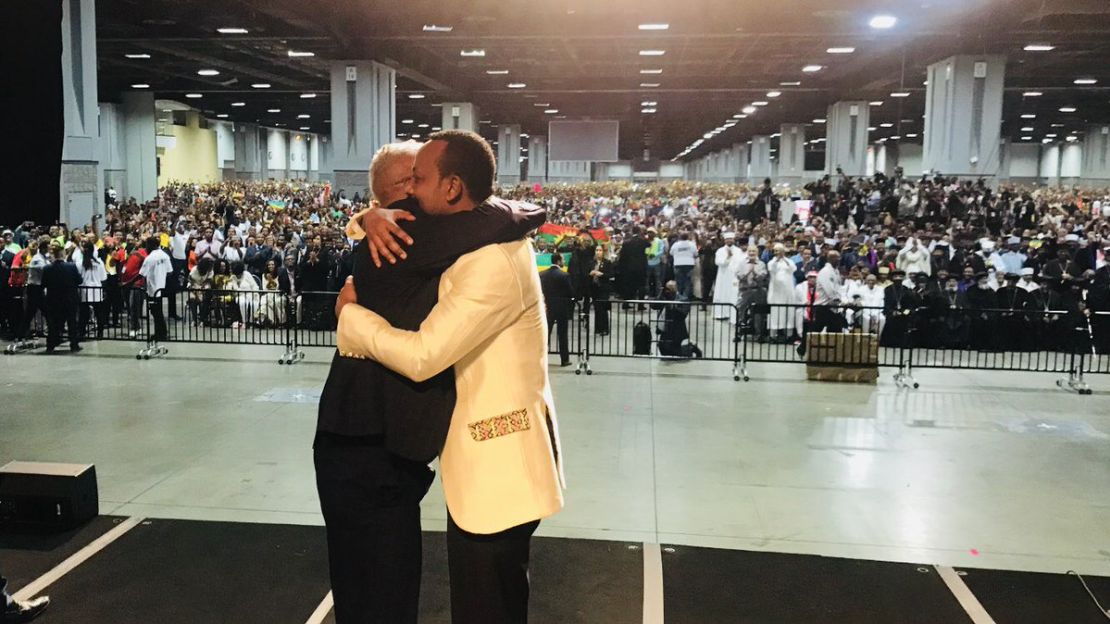

At 6 am when Gutama Habro arrived at the Target Arena in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the line for tickets already snaked around the block. Within hours, 20,000 fans had packed the venue. “People around me were crying,” says Gutama, a 28-year-old medical laboratory scientist. “Seeing this was a dream come true.”

Gutama wasn’t at a pop concert. This was the final leg of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s three-city American tour. Held in July, it was the first time the 42-year-old had visited the more than 251,000 Ethiopians living in the United States, many in self-imposed exile – fleeing ethnic clashes, violence, and political instability in their homeland. “The level of hope was something we had not seen since the election of Barack Obama,” says Mohammed Ademo, an activist who fled to the US in 2002 and founded OPride.com, a news outlet that was blocked for years at home.

Since taking office on April 2, Africa’s youngest head of government has electrified Ethiopia with a dizzying array of liberal reforms credited by many with saving the country from civil war. Abiy has freed thousands of political prisoners, unblocked hundreds of censored websites, ended the 20-year state of war with Eritrea, lifted a state of emergency, and planned to open key economic sectors to private investors, including the state-owned Ethiopian Airlines.

In the capital city of Addis Ababa, taxi windscreens are plastered with Abiy stickers, while citizens are changing their Whatsapp and Facebook profile pictures to pro-Abiy slogans and spending their money on Abiy T-shirts. Elias Tesfaye, a garment factory owner, says that in the past six weeks he has sold 20,000 T-shirts bearing Abiy’s face, which cost about 300 birr ($10) each. In June, an estimated four million people attended a rally Abiy gave in the capital’s Meskel Square.

Tom Gardner, a British journalist who lives in Addis Ababa, says there is an almost religious fervor to what has been dubbed “Abiymania.” “People talk quite openly about seeing him as the son of God or a prophet,” he says.

On the verge of civil war

A prime minister’s wardrobe doesn’t often attract attention. But the blazers with purple or green and gold trim that Abiy wore on his US tour were not just a natty pick: this was traditional Oromo attire.

That’s significant. Abiy is Ethiopia’s first prime mister from the country’s biggest ethnic group, the Oromo, who make up one third of its 100 million people. Ethiopia has more than 90 ethnic groups, and for decades the country’s politics have been organized along these divisive lines.

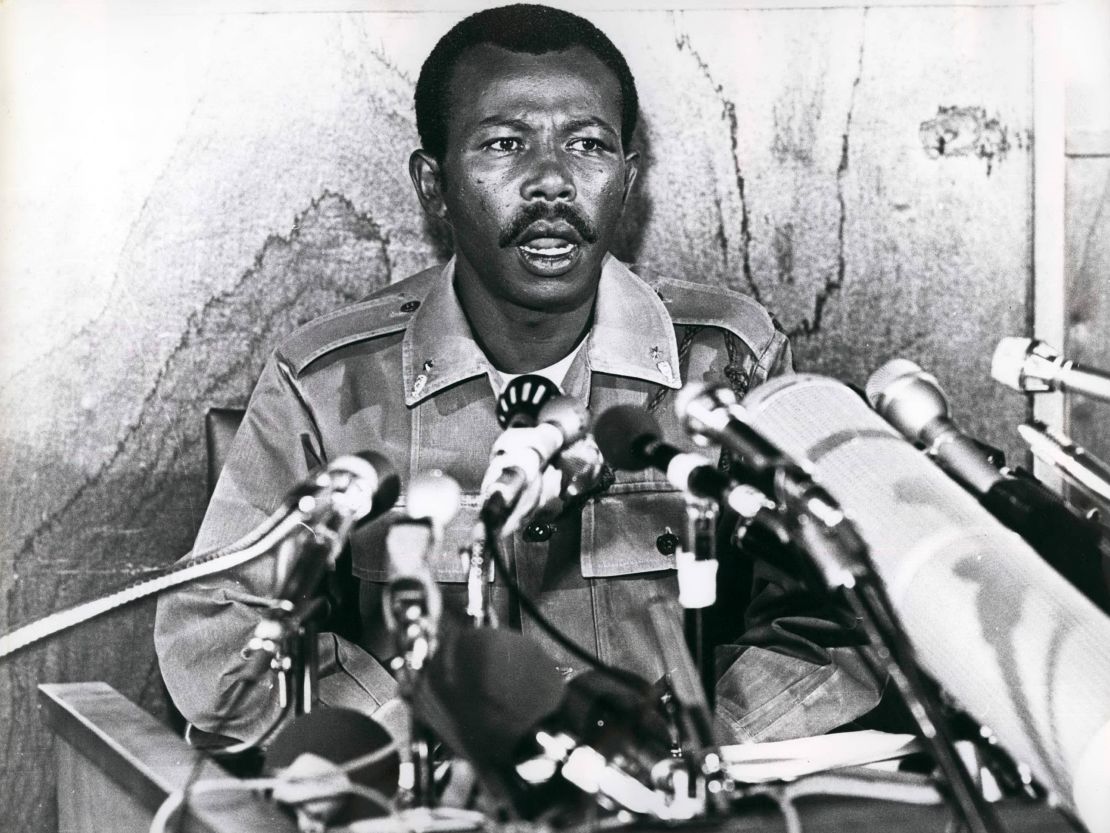

In 1991, the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) toppled the dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam, whose communist regime had imposed military rule since 1974. Mengistu had thousands of his political opponents murdered and ignored a famine that killed one million people – a tragedy that found a global spotlight in the 1984 Band Aid charity record “Feed The World.”

The TPLF began as a small band of guerrilla fighters from the Tigray ethnic group, who account for six percent of Ethiopia’s population. As the party prepared to assume power, in 1989, it engineered a coalition with larger ethnic groups, such as the Oromo and Amhara, to bolster its legitimacy. The catch? “The TPLF formed the rest of the parties – they don’t have an autonomous existence,” says Tsedale Lemma, editor-in-chief of the Addis Standard, an independent newspaper.

Until Abiy, that coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), ruled with an iron fist. Government marginalizationof other ethnic groups prompted an exodus of professionals from the nation and secession cries from the Oromo at home. Government plans to annex Oromo farmland in order to expand Addis Ababa saw civil unrest explode across Ethiopia in recent years.

As the country disintegrated into chaos, in February 2018 Prime Minister Haile Mariam Desalegn did something African leaders rarely do. He quit. A state of emergency was called for the second time in 18 months and an internet blackout followed, including in the capital. “It was devastating for the economy,” says Tsedale.

“Everyone feared that if Ethiopia didn’t get an Oromo leader then the nation would collapse into civil war,” says Abel Wabela, a former engineer for Ethiopian Airlines, who was imprisoned for blogging about democracy under the previous administration. “Luckily, we got Abiy.”

The selfie prime minister

Abiy is nothing like those who came before him. He hugs politicians in public, takes selfies with fans, and doesn’t just smile for the cameras, he beams. His message to Ethiopia’s ethnic groups has been: “Take down the wall, build the bridge.”

In Minnesota, he asked the crowd to “medemer,” literally, be added to one another. “If you want to be the pride of your generation,” he said, “then you must decide that Oromos, Amharas, Wolaytas, Gurages, and Siltes are all equally Ethiopian.” In a country physically carved up along ethnic lines (many groups were given their own region to govern in 1991, as the country moved to ethnic federalist politics), this is a revolutionary message.

“He talks in a language people understand,” says Ademo, who joined Abiy’s US tour as a consultant on the American diaspora. Embracing the previous government’s enemies is a classic Abiy move. “People cry because for the first time they see light at the end of the tunnel. People have finally found the leader they’ve been waiting for.”

It helps that Abiy’s own identity bridges ethnic groups: his father is a Muslim Oromo while his mother was a Christian. He is fluent in Oromo, Amharic, Tigrinya as well as English. In Minnesota, he addressed the crowd in all three of these Ethiopian languages, as well as some rehearsed Somali for attendees from Ethiopia’s restive eastern region.

His professional experience is also diverse. In the 1990s, Abiy was a United Nations peacekeeper in Rwanda, he subsequently headed Ethiopian cyber security agency INSA and served as minister of science and technology before shrewdly leaving the embattled central government to become deputy president of the contentious Oromia region, aligning himself with that area’s struggle.

As Abiymania swells, there is talk of a “brain gain.” Ethiopians are being pulled into his orbit, and back to a country that now has the fastest growing economy in Africa. Ademo returned to Addis last month. Olympic Marathon silver medalist Feyisa Lilesa plans to do the same in September. He has been exiled in the US since crossing his arms at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympic Gamesin protest against government land grabs and ethnic killings. “If I had gone back, I would have been killed,” says the runner. Former political prisoner and democracy blogger Atnaf Berhane says that in Addis “for the first time in six years, I don’t feel like I’m going to be arrested.”

Abiy’s own safety might not be so assured. In June, a bomb was detonated at a rally he gave in Meskel Square, in what was seen as an assassination attempt. While Tsedale says many of the old guard are “disgruntled” by Abiy’s disrupting of their political hegemony, there is also a pragmatic “reformed wing” of the TPLF that backs his leadership.

Arkebe Oqubay, a founding member of the EPRDF, senior figure within the TPLF and government minister, appears to be in their ranks. “Abiy is young and he brings vigor,” he says. “The whole country should get behind him.”

A cult of personality?

There’s a slightly awkward sticking point in Abiy’s success story. While he presents himself as a liberal champion, in four months in office he hasn’t given an interview. Private media, for a time, stopped being invited to government events for “reasons we don’t understand yet,” Tsedale says. Consequently, a question mark hangs over much of Abiy’s worldview and biography, other than the fact he is married with three daughters. On August 25, however, he did hold a three-hour press conference – his first – at which Tsedale says he seemed “relaxed and convincing.”

Having already visited Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the US and Djibouti, Abiy is the region’s “most active diplomat by some way,” Gardner says. Ademo notes that he has taken tough questions from the public at multiple town halls.

Official news now comes almost exclusively via the Twitter account of Abiy’s chief of staff, Fitsum Arega, who posts his boss’ achievements in real time. As ethnic violence in rural areas has claimed lives in recent weeks, Abiy’s silence and Fitsum’s cheer leading have jarred. “You have people being lynched in Shashemene and then he [Fitsum] is tweeting about Abiy visiting the Jimma Industrial Park. It’s ridiculous,” says Mula Geta, an Ethiopian living in Tel Aviv, Israel.

And the government still appears to be turning off the internet during flashes of unrest.

“The government should be doing more to address such violence and ensure there are credible investigations into killings,” says Maria Burnett, associate director of the Africa division at Human Rights Watch.

Furthermore, while Abiy has apologized for the torture that political prisoners endured in jail under previous governments, there is no sign that offending guards will face charges.

Ahmed Shide, minister of government communication affairs, did not reply to CNN’s request for comment. Abiy did not reply to multiple CNN requests for interview.

Perhaps the biggest concern is that “Abiymania,” and the faith it confers, will blind Ethiopians to the potential flaws of their leader, and weaken the democratic process. Natasha Ezrow, a professor in the department of government at Essex University in England, says: “We should be cautious of leaders who emerge and appear to be a messiah for everybody.” Ethiopia, she adds, has “no institutions for democracy” and is “used to a strong man.” Unless Abiy implements significant checks on his own power, then it will be hard to avoid a dictatorship, she says.

For now, Ethiopians worldwide are hoping that will not be the case.

“For a country like Ethiopia, Abiy is one in a million,” says Geta. “He really could be one of the greatest leaders that Africa ever saw.”