Story highlights

Horticultural therapists work with plants to improve clients' health

Studies show that horticultural therapy shortens hospital stays

Plants and people have an ancient bond

It’s a warm, sunny morning in Tony Wright’s lush backyard in Roswell, Georgia. The retired human-resources manager sits on a folding chair and gazes around in contemplation, surrounded by shade trees and chirping birds. He sips coffee and reads from his 12-step program book, “Daily Reflections.” Then he takes a slow walk through his garden, observing how his plants are doing and what they might need.

This is how Wright begins every morning. It’s a routine the youthful-looking 68-year-old began after years of struggling with addiction. He starts to pot petunias, digging his large hands into the soil and pouring water from a watering can to nourish the transplant.

“Even if I’m just watering a plant or trimming a bush, it just gets me in touch with nature, and I try to listen to what nature’s trying to tell me that morning,” Wright said.

“It makes me feel lighter. Depression made me feel very heavy.”

Four years ago, Wright was introduced to “horticultural therapy” while in treatment at a mental health center called Skyland Trail in Atlanta.

Horticultural therapy is a professional practice that uses plants and gardening to improve mental and physical health. A horticultural therapist works with any group that can benefit from interaction with plants, including veterans, children, the elderly and those dealing with addiction and mental health problems.

“I was having severe issues with depression and alcoholism, and they were taking quite a toll on my life, quite a toll on my family and relationships,” Wright said.

Nearly every day for three months, Wright spent time in Skyland’s greenhouse.

“I was introduced to a situation where it’s like, ‘can you do flower arranging? Can you repot plants, and can you prune plants?’ I said, ‘Well, I’ll try it.’ “

“It was therapy, and I didn’t know it was therapy. No one was sitting down saying, ‘OK, now we’re in therapy, and here is what we do,’ ” he said. “When I’m touching a plant … it’s a very calming experience.

“It was really, really a godsend for me.”

The mental and physical benefits of nature

Horticultural therapy is rooted in the idea that interacting with plants can bring about well-being, whether it’s tending a garden or just having plants in your home.

Many studies have found that just being in nature – such as taking a walk through a garden, a park, a forest – can improve not only your state of mind but your blood pressure, your heart rate and your stress hormone levels and, over time, can lead to a longer life.

But taking care of a plant or a garden with guidance from a therapist goes a step further.

The clients “are the caretakers, and that’s an important role for people who are on the receiving end of medical care,” said Joel Flagler, a professor of horticultural therapy at Rutgers University.

Studies have found that horticultural therapy supports recovery and improves mood, resulting in shorter stays for many populations, such as mental health facilities and hospitals.

One study Flagler cites out of Rutgers looked at the impact of Japanese gardens on a group of Alzheimer’s patients.

“Patients with advanced dementia were seen to have greatly improved short-term memory retention after a horticulture session,” Flagler said. “Some of the participants remembered the chirping sound of a cricket in the garden almost two weeks after the event.”

What we can learn from plants

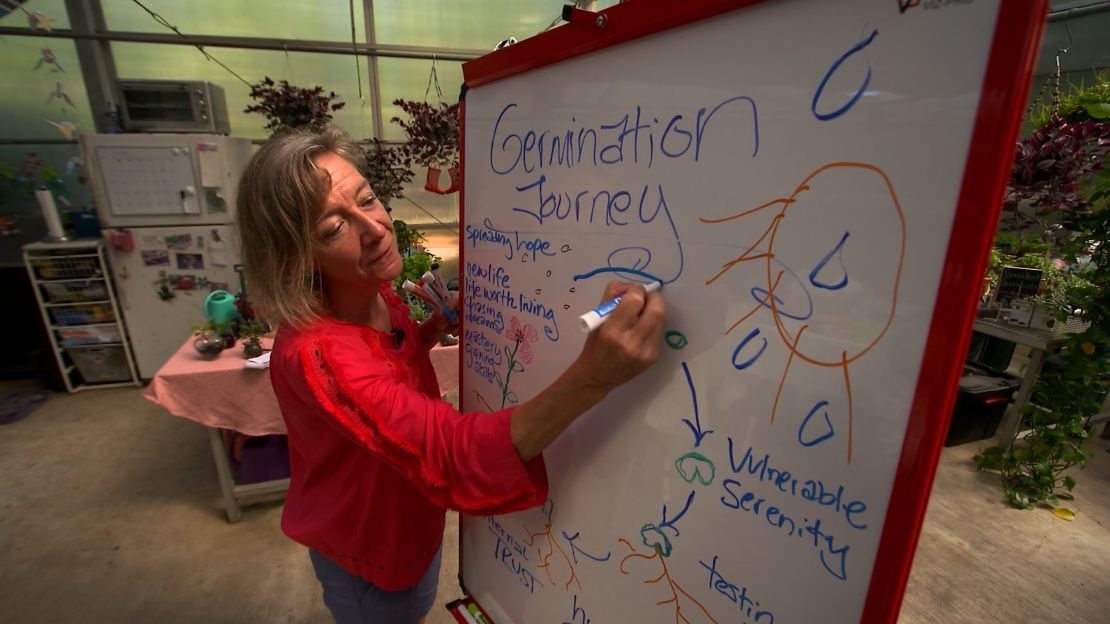

When CNN visited Skyland Trail in June, a group of 20-somethings were gathered in the greenhouse as horticultural therapist Libba Shortridge excitedly pointed out how a seed’s journey into a plant parallels the recovery process for those with mental health issues.

As she spoke, she drew on a dry-erase board. “Come winter, when things are dormant and nature sheds its leaves, it looks like there’s no hope. There actually is,” Shortridge said.

“Seeds have these cool internal clocks that tell them when they can bust open and form roots!

“What do you need to grow? Sun, water, confidence, courage!”

A participant added, “patience!!”

Shortridge echoed, “Patience! I love it!”

The group then took seeds into their hands and planted them in one of Skyland’s many gardens. Birds chirped overhead, and a cool breeze blew through.

Shortridge pointed out how the sun filtered through the leaves like a projector, creating designs on the grass. “Do y’all notice the pattern?”

Observing is a big part of the therapy.

One young man read the Serenity Prayer after a planting. “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Gardening also has physical benefits, such as increased hand-eye coordination and finger flexion.

There’s the lifting of soil, “digging with shovels and standing for increasingly long periods of time, which helps their balance, especially when they’re walking down to the garden carrying a tool,” Flagler said.

“Often, our clients are sure that their seeds won’t grow. But as the seed germinates, as a seedling develops, it proves to the individual that their actions made a difference. As the plant thrives, it builds self-esteem, it builds confidence, and it makes the person feel like it’s their success.”

Helping those in wheelchairs, special needs

And for those in wheelchairs, container and box gardening brings the soil and plants to the level they need. Extender tools help them reach, and horticultural therapists teach them how to use the tools.

Rachel Cochran started the Atlanta nonprofit Trellis Horticultural Therapy Alliance after her daughter was hit by a car, causing a traumatic brain injury.

The horticultural therapist found that there weren’t many opportunities in the city for special-needs students to access special gardens.

The Georgia Tech grad got a grant to help her daughter’s school create a sensory garden that students in wheelchairs can access.

It’s not built yet, so for now, she brings nature to the classroom.

“We bring in flowers. We make homemade birdseed so they can put their hands in a big bucket of seeds. We bring in pine cones, mosses, bright flowers, yellow and red. We put a bird feeder right on the window,” Cochran said. Not only is it stimulating for the students, she said, “it’s also boosting the mental state and health of the teachers. Being caretakers can be very mundane and repetitive.”

Today, she has multiple projects across the city, including a garden next to an elder residence high-rise where she works with a small group of seniors, planting, tending and tasting.

An ‘ancient bond’

“Plants are unique in that they offer sensory stimulation,” said Flagler, who is also the agricultural extension agent for Bergen County, New Jersey. “Fragrance, texture, taste and sound,” like leaves rustling in the wind and bamboo creaking.

Flagler says plants reward the individual with change: a new leaf, a new fruit, a new flower, fragrance.

He points out that humans evolved in a green world with plants over millions of years. Trees and vegetation have always provided us food, medicine and shelter. “People and plants share an ancient bond.

“Now, we’re able to use that people-plant connection for therapy and rehabilitation.”

For prison populations, Flagler says, there are reduced recidivism rates among inmates who participate in horticultural therapy programs. In part, the program teaches “green skills” so that people can learn a trade.

“I work closely with the landscape industry. If we can get that young person to feel like they have a green thumb – propagating, pruning – then they can get a job.”

Some universities, including Colorado State University and Rutgers, offer degrees in horticultural therapy.

Other schools offer concentrations through their horticulture programs and certificates through the American Horticultural Therapy Association.

Giving back

In his lush backyard in Georgia, Tony Wright says that working in a garden helps him realize he’s part of something much bigger. His daily struggles seem diminished.

Join the conversation

Wright now volunteers at Skyland Trail, his old stomping grounds, and in other programs across the South.

“The garden is a living thing. So it has its own flow. Sun comes up; the sun goes down. Plant responds to light; it responds to darkness. We do the same thing,” Wright said.

“The plant goes to sleep at night. What’s my rest protocol look like? Am I up to 3 o’clock in the morning, or do I get a good night’s rest?”