Story highlights

Dementia is one of the top 10 causes of death for women worldwide

Researchers are looking at factors within a woman's life that could contribute

At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Chicago this week, researchers are exploring biological and social differences that might explain why more women than men develop Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia.

A study to be presented at the conference found a link between a lower risk for dementia and the number of births a woman has. Women with three or more children had a 12% lower risk of developing cognitive issues than a woman with only one child, according to initial results of the study of nearly 15,000 women. Pregnancy failures, however, increased a woman’s risk, according to the Kaiser Permanente study. Compared with women who never lost a pregnancy, women with three or more miscarriages had a 47% higher risk for dementia.

It’s just one of several studies at the conference looking at how pregnancy, female hormones, age of menarche and menopause, and even a woman’s innate cognitive advantages might affect her risk for the condition.

A woman’s disease

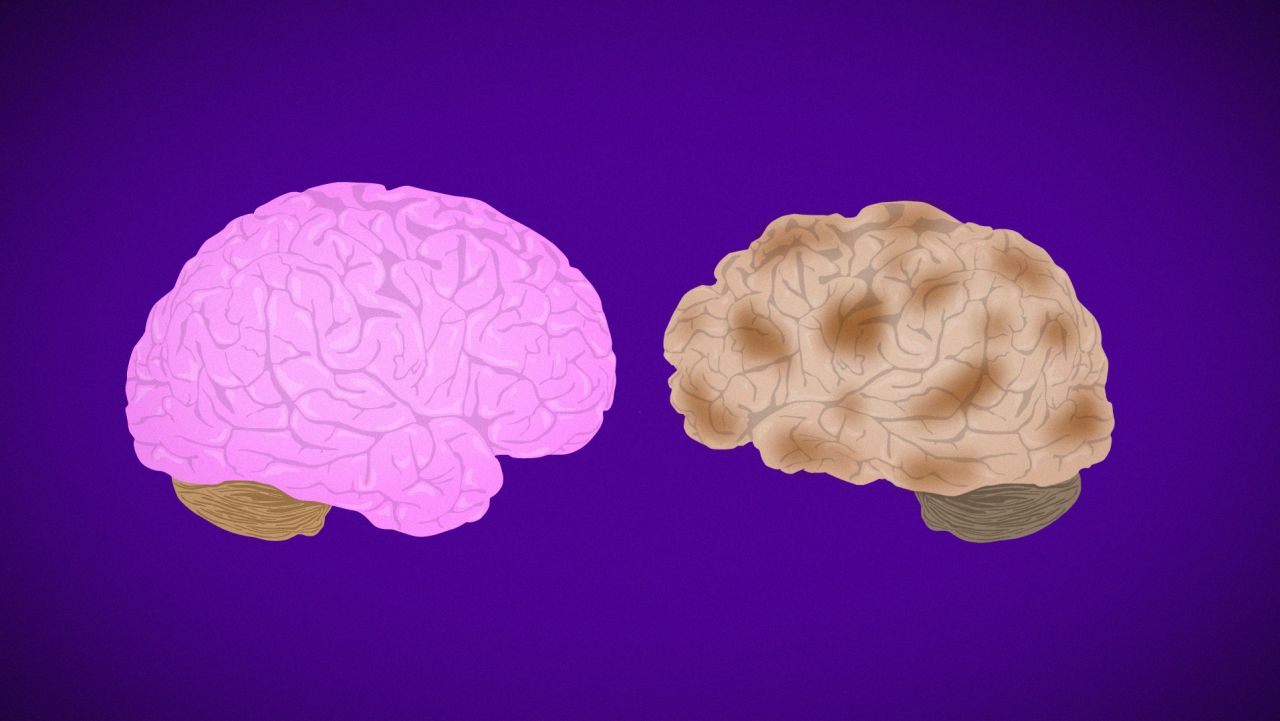

Alzheimer’s is a progressive mental deterioration of the brain that destroys memory and thinking skills until the person is unable to do even the simplest of tasks. The disease is thought to be caused by a buildup in the brain of beta amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles called tau.

Of the approximately 50 million people around the world living with dementia and Alzheimer’s, most are women. In the US alone, two-thirds of the 5.7 million Americans living with Alzheimer’s are female. Women 60 and older are twice as likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s as breast cancer.

The results are devastating. The World Health Organization calls dementia one of the top 10 global causes of death for women. In the US, Alzheimer’s is now the sixth leading cause of death, killing more seniors than breast cancer and prostate cancer combined. In England, Wales and Australia, 2016 death statistics show that dementia and Alzheimer’s kill more women than heart disease.

Yet for many years, experts say, science wasn’t focused on why Alzheimer’s affects more women than men.

“Age is the greatest predictor of Alzheimer’s, so for a long time, there was this notion that women are at higher risk only because they live longer,” said University of Illinois psychology and psychiatry professor Pauline Maki, who is presenting at the Alzheimer’s conference. “No one was paying attention to what was going on in the female brain throughout a woman’s life.”

“I was requesting grant money to research estrogen, and I was getting comments from reviewers asking, ‘Why are you doing this?’ ” said presenter Carey Gleason of the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Over the past few years, that’s been changing.

“We’re at a very exciting time in the field,” said Rachel Whitmer, professor of public health sciences at the UC Davis School of Medicine. “Rather than just brushing it aside as ‘women live longer and that’s the end of story,’ science is now breaking it down to a deeper level to understand the where, when, why and how.”

Role of reproductive life

The Kaiser Permanente study, which looked at number of births and dementia risk, followed women who have used the company’s health care most of their lives. This allowed researchers to access each woman’s medical records between 1964 and 1973 and then again from 1996 to 2017.

That was important, the researchers said, because they weren’t relying on a woman’s memory of her reproductive and medical history, a key flaw in many study designs.

“I myself have trouble sometimes with remembering what happened last week,” said Whitmer, who co-led the study. “But we actually have the questionnaires they filled out from the ’60s and ‘70s.”

“We could then compare that to their midlife risk factors such as hypertension, stroke, diabetes and heart disease and factor those out,” added Paola Gilsanz, a staff scientist at Kaiser Permanente who co-led the study. “So in that sense, it’s very, very powerful.”

When the study began in 1964, all of the women were 40 to 55. Their medical records documented reproductive history, education, race and midlife health status, as well as when each woman began menstruating, when she went into menopause and the length of those reproductive years. Dementia diagnosis and later-life chronic conditions, such as heart failure and diabetes, were pulled from records between 2016 and 2017.

In addition to finding that multiple pregnancies were protective against dementia but multiple miscarriages were not, the study found that women who were fertile for only 21 to 30 years had a 33% higher risk for dementia than women who were fertile for a longer time period.They also found that women who started their first menstrual cycle at 16 or older were 31% more likely to have cognitive problems than women who began at age 13.

What do all of these results mean? It’s too early to tell, Whitmer said.

“This is an observational study,” she said. “It doesn’t tell you the mechanisms, but it’s telling you who is at higher and lower risk. This information allows basic scientists to take the next step and do more experimental work and really delve in.”

The Kaiser study conflicted with recently published research that found South Korean and Greek women who have given birth five or more times may be 70% more likely to develop Alzheimer’s later in life.

“Korean, Greek and American women are pretty different genetically,” said Alzheimer’s researcher Dr. Richard Isaacson, who was not involved in either study. “You have to be very careful with generalizing these studies. Take for example, studies done in China on stroke. You can’t generalize those findings to stroke patients in the United States unless they’re Chinese American or born in China and moved here.

“Alzheimer’s disease is a life course disease in my opinion,” said Isaacson, who founded the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “The risk starts in the womb and is then affected by your genes, your early life risk factors, your educational attainment, your diet and exercise and so much more.”

Better cognitive assessment

Another study presented at the conference focused on the need for more accurate screening tests for Alzheimer’s – tests that would consider a woman’s innate advantage over men in verbal memory.

“If you go to the store without your grocery list, a woman is going to do the better job of remembering it,” said Maki, who led the study. “A man will be better at visual-spatial things, like finding the way home.”

Cognitive tests used to diagnose Alzheimer’s rely heavily on recalling word lists, stories and other verbal materials. That means women who have mild cognitive decline can score as normal, Maki said, thus keeping them from possibly beginning medication and making appropriate lifestyle changes. It could also mean that some men might get a false positive on the memory test, she said, and be diagnosed with brain changes when they are actually normal.

Using data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, a multicenter study designed to develop biomarkers for Alzheimer’s, Maki found that women performed better even when they had the same level of disease as a man. It also took high levels of disease for that advantage to be eliminated. This could explain, she said, why women seem to deteriorate faster than men after diagnosis: They are further along in the disease.

Maki then tested a new scoring mechanism for the Alzheimer’s memory test, making it harder for women to get a “passing grade” while making it easier for men. She found that 10% of women who showed Alzheimer’s pathology on brain scans could now be identified; she also found that 10% of men who would have been considered cognitively deficient now ranked normal.

“More research is needed to apply these results to larger populations,” Maki said, “but it shows the need for a re-evaluation of the tests we use to diagnose Alzheimer’s so both men and women can get the help they need.”

The role of estrogen

A third study at the conference, presented by Gleason of the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, looked at more recent studies on the cognitive effects of hormone replacement therapy, a topic with a controversial history.

“We’re recognizing that our models were too simplistic,” she said, “and that there’s a lot more things to pay attention to, including a woman’s underlying health, genetic profile and the timing of when hormone replacement therapy is started and stopped.”

For years, science believed that giving women hormone replacement therapy, or HRT, at menopause was beneficial for the aging brain and would help prevent heart disease. But then came shocking preliminary results from the Women’s Health Initiative, a long-term national study designed to look at ways to prevent heart disease, osteoporosis and breast and colon cancer in women.

Those 2002 and 2004 results found that the estrogen-progesterone combo of HRT actually increased the risk for heart disease as well as stroke, blood clots, dementia and breast cancer.

The use of HRT plummeted. Then, 10 years later, the Women’s Health Initiative reversed its findings. Because the original analysis looked at older women, who were already at risk for heart attacks, blood clots and stroke, the initial results were flawed because they failed to consider a woman’s age at the start of replacement therapy.

Today, it’s believed that HRT could be helpful in controlling menopausal symptoms at the time when most women undergo the change, in their late 40s and early 50s, when their risk for chronic disease is lower.

Women who wish to take hormones later in life, when the risk for blood clots, stroke and cancer is higher, should look at their risk factors and discuss the option carefully with their doctor.

HRT also might not help the older brain: Women who start hormone therapy in their 70s, said Gleason, showed persistent declines in cognition, working memory and the ability to organize and get things done, which is called executive functioning.

Join the conversation

For younger women, Gleason said, more recent research has found no cognitive harm or benefit to several forms of HRT if started within a few years of menopause, unless the woman has Type 2 diabetes.

“If you’re a diabetic, you’re at increased risk to progress to dementia, period,” she said. “But the risk is bigger if you’re on hormone therapy.”

It’s complex and often confusing, but researchers in the field say that all signs point to more definitive answers within the next five years.

“We need a personalized medicine approach to menopausal hormone therapy,” Gleason said. “We are in a really exciting time in terms of understanding the complexity of estrogen, menopause and menopausal hormone therapy and how all of these things combine.”

“No one size fits all,” agreed Isaacson. “We need to use imaging, biomarkers, blood biomarkers, clinical history, such as when they started their menstrual period, when they stopped. Different women are going to need different therapeutic interventions. This will be precision medicine at its finest.”