Jasmine Glenn’s friends remember late-night phone calls from her, sobbing and saying she was ready to kill herself, knife in hand.

The world saw her as a man. To pretend she was one, she behaved recklessly. She drank heavily and then ran through bonfires. She raced her car down dark country roads in rural Michigan in the middle of the night.

“I was trying to drink myself to death to escape who I was,” she said. “I wasn’t allowed to be myself, so I didn’t want to be anyone else.”

Then, at 35, she realized what she needed to do to be herself: accept that she’s transgender and live openly as the woman she always knew she was.

To do that, she said, she had to “fix” her body. But after the battle with herself came the battle with insurers.

Not all transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals need medical care to transition. And not all identify as a man or woman. Some resent the pressure to conform their bodies to traditional ideas about what makes a man a man or a woman a woman – especially as a growing body of research questions the relationship between sex and gender.

But those who seek solace in a typically masculine or feminine form say they are caught in a painful cycle of constantly having to prove that they are who they say they are to meet criteria set by physicians, insurance companies and lawmakers.?

And they fear that it’s about to get harder.

The Trump administration has signaled its intention in recent months to rewrite a federal rule that bars health care discrimination based on gender identity. In its current form, that rule is one of the precious few tools transgender patients have to fight insurance denials for various medical treatments and procedures that fall under the broad umbrella of gender-affirming or transition-related care. Even with the rule in place, Jasmine and four other patients in different states detailed protracted battles for coverage.

Jasmine began taking hormones in 2012, before she had insurance, paying out of pocket. In 2014, she got on a Michigan Medicaid plan offered by Priority Health. For the past four years, she’s been fighting to get coverage for vaginoplasty and facial feminization. Her doctors say the surgeries are medically necessary to treat her gender dysphoria – the diagnostic term for the distress she feels over the conflict between her gender and the sex she was assigned at birth.

After rounds of appeals, she won pre-authorization for vaginoplasty but not a prerequisite hair removal procedure. After she was approved for hair removal and started treatments, her pre-authorization for vaginoplasty expired. Priority declined to again pre-authorize the surgery in 2018 on the grounds that it was no longer a benefit. Now, she is appealing the denial for vaginoplasty while her battle continues for facial feminization surgery.

“Apparently, I am getting hair removed for prep for a surgery I now can’t get,” she said. “This crap is why I wish I were dead.”

Priority declined to comment on Jasmine’s case, citing privacy laws. “Please know that we have dedicated doctors, nurses and clinicians on staff who work closely with our members to ensure they have the access to the care and treatment they need,” the insurer said in a statement to CNN. “Our members’ health and safety is always our first priority.”

A landmark protection for transgender patients

Until recently, American health insurers routinely defined gender-affirming procedures like the ones Jasmine is seeking as ineligible for coverage, even though the consequences of untreated gender dysphoria – including depression, substance abuse and suicide – are well-documented.

A series of protections enacted during the Obama years attempted to make it easier for patients to access coverage for such care. The most significant was a provision of the Affordable Care Act known as Section 1557, which banned discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability in federally funded health care facilities and insurance plans. A rule enacted in 2016 interpreted the ban on sex discrimination to include discrimination on the basis of gender identity. Meanwhile, 19 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws or mandates against blanket exclusions for gender-affirming treatment in benefits packages.

Timeline of transgender health care rights

These measures applied to a sizable chunk of carriers, and many of them rushed to scrub their plans of exclusions and add benefits for transition-related care. A recent study linked the increase in coverage to an uptick in transition-related procedures from 2000 to 2014.

Although progress has been steady, “it’s still very uneven based on what kind of coverage you have and where you live,” said Harper Jean Tobin, director of policy for the National Center for Transgender Equality, a nonprofit advocacy group.

Though such exclusions are no longer permitted, CNN found that some policies offered on the ACA marketplace in 2018 still refused to cover gender-affirming procedures. One insurer, HealthFirst, acknowledged that the policies we found online were outdated and thanked us for pointing them out.

Two others, Medica and Oscar, said they did not cover such procedures because they were not included in a state’s Essential Health Benefits, a set of services insurers are required to cover under the ACA. Nothing in state or federal law precludes insurers from offering benefits that are not spelled out in a state’s Essential Health Benefits. But in a state without explicit anti-discrimination mandates, health care experts say there’s little incentive for an insurer to be the only one offering gender-affirming benefits – especially if no one is holding them accountable.

Further complicating matters is a lawsuit challenging Section 1557 from several religious health care providers, including Franciscan Alliance Inc. Two insurers, Oscar and HealthFirst, told CNN that a preliminary injunction meant that they did not have to cover transition-related treatment – an interpretation that LGBTQ patient advocates and legal experts say is incorrect.

Ambetter and MercyCare did not answer repeated requests for comment. Dean Care and MedMutual declined to comment.

The trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) said carriers comply with state and federal laws and work to ensure that members have access to services they need. If a patient encounters barriers, “we would encourage them to have conversations with their health care plans to help ease the path to access to care,” said Cathryn Donaldson, communications director for the association.

Now, LGBTQ advocates fear that Section 1557’s gender-identity protections may be rolled back. “The Trump administration, in the last year-plus, has been sending signals that it wants to not only not enforce but change its interpretation of health care law to exclude protections for transgender people,” Tobin said.

On February 13, government lawyers said in a court filing that the US Department of Health and Human Services had submitted a draft of a proposed rule to the White House, suggesting that it had come up with new regulations for Section 1557. The action was confirmed in a notice on the Office and Management and Budget’s website.

“A federal court struck down the gender identity provisions of the rule as contrary to law and issued a nationwide injunction barring HHS enforcement. We are reconsidering the reasonableness, necessity, and efficacy of the rule in light of the injunction and will continue to vigorously enforce all prohibitions on discrimination in health care according to the law and court orders, before, during, and after any rulemaking,” Roger Severino, director of the Office for Civil Rights within HHS, said in a statement to CNN.

Fighting to be herself

Nearly seven years ago, Jasmine was trapped in a cycle of despair fueled by alcoholism. After long days working in restaurants, she would often drink with friends in bars or their homes to the point of blacking out.

“I preferred to be in that Salvador Dali level of drunk, where everything’s melting off the walls,” she said. “I was hurting, and so I wanted to watch the world burn.”

She began to rethink her life in 2011, while she was under supervised probation for her second drunken driving arrest. She was living in a trailer in her hometown of Allendale, Michigan – a semirural suburb of Grand Rapids, in the conservative part of the state, where hospitals and stadiums are named for the family of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

Jasmine’s driver’s license had been revoked, and she was unable to leave home except for work and Alcoholics Anonymous. Sober for the first time in her adult life, she started looking online for the language to describe what she was experiencing. She heard success stories that defied the sensationalized portrayals of people who identify as transgender that she grew up watching on daytime talk shows. She connected with others who shared her anxieties and identified what she’d been trying to suppress with alcohol.

After coming out to friends and family, she took the first step toward changing her body to match her gender, a process referred to as physically or medically transitioning. In 2014, she applied for insurance through a Michigan Medicaid plan offered by Priority Health.

It took her months to find the right doctor and seek referrals, then months more of filing claims, receiving denials and appealing. Then came hearings in which, she says, Priority’s representatives misgendered her by calling her a man even though she had been referring to herself in paperwork as a woman. She says they questioned her need for surgery despite her doctor’s recommendations. She spent countless hours on the phone and researching court cases that she could cite as precedents in her favor.

Although the battle consumed her waking hours and frustrated her, it was the only thing keeping her from taking her life, Jasmine said. “I was so angry, I didn’t understand why they were making it so hard,” she said. “There was only one other option, and I couldn’t do that, because that would mean letting them win.”

Navigating a jurisdictional maze

Jasmine is not alone. Other people who identify as transgender with different types of plans from states across the country also described running into red tape and denials when they tried to get coverage.

Like Jasmine, Derrick Robinson turned to alcohol to forget who he was before he transitioned. Back then, he identified as a woman and a lesbian. His 20s are a blur of blackouts, clashes with family and run-ins with police, he said. Then, he started dating a woman he knew from high school. As they grew close, she came to see how Robinson struggled with his identity and encouraged him to transition.

Robinson started taking testosterone in June 2016 as part of his transition. Two months later, he said, he started wearing a chest binder to minimize the appearance of his breasts and help him look more masculine. His chest was the first thing people would look at when they saw him, he said. Their confused looks made him paranoid and fearful for his safety.

By the time the couple married in October 2016, he had a mustache above his lip, and his hairline was receding. A few months later, his voice took on a raspy edge. He was eager to undergo surgery.

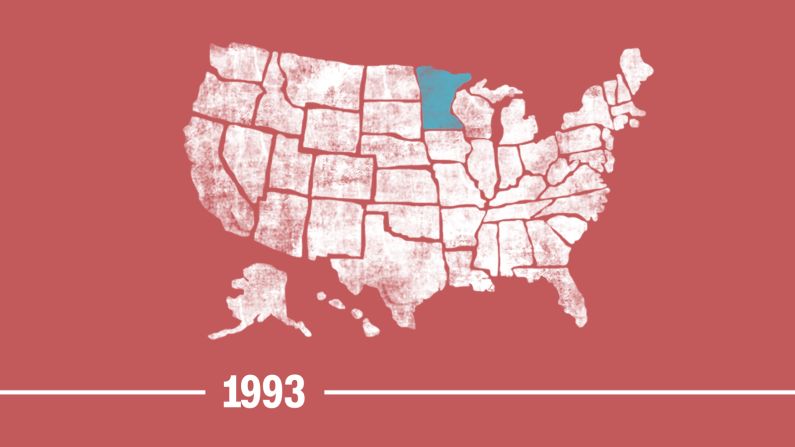

An exclusion for gender reassignment surgery was written into the group plan offered by his employer, even though his home state, Minnesota, forbids discrimination based on gender identity in group and individual plans. A spokesman for his insurer, Medica, told CNN that it follows whatever the employer chooses to include or exclude in self-insured group plans like Robinson’s, which are subject to some federal laws but not the ACA. Medica denied his request for gender reassignment surgery, citing the exclusion. But when his psychologist provided a letter recommending bilateral mastectomy to treat Robinson’s gender dysphoria, Medica granted the request. Robinson had surgery in October, and after he recovered, he and his wife burned his bras and chest binders. Now, for the first time, he’s not afraid to look at himself in the mirror.

“I just feel like I see the person I should’ve been seeing the whole time,” he said. “I’m finally living the life I want to live.”

Brynn Mahsman tried to challenge an exclusion for gender confirmation surgery in her employer’s group plan in January 2016, thinking Section 1557 and Nevada’s anti-discrimination insurance mandate would be on her side. A representative for her insurer told her the plan complied with the most recent requirements of the ACA but noted that Health and Human Services had not yet “issued guidance or regulations with respect to many aspects of these laws,” which was true at the time. She would later find out that others like her – with self-insured group plans that are not subject to the ACA – have filed complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which enforces workplace anti-discrimination laws. But she wasn’t aware of her rights. By the time she had invested the energy in educating herself on the jurisdictional maze of health plans, she had lost her job and her benefits. Now, the software engineer said she works for a new company with benefits for gender-affirming procedures, and she has hope.

Autumn Trafficante says she spent most of her 20s “trying to do the guy thing” after puberty forced upon her a masculine visage. By her late 20s, it got to the point where she couldn’t stand to catch her reflection in a car window – let alone a mirror – and see someone she didn’t recognize. She tried to feminize her appearance with clothes and makeup, she said, only to have her identity undercut by a stranger calling her the wrong gender.

“It really wears on you when your life is made up of moments like that,” she said. “I woke up more days than not thinking about killing myself.”

Right before her 28th birthday, she decided she’d had enough and put together a timeline and a budget for transitioning, she said. Then, she hit a snag with her marketplace plan. Despite letters from her physicians attesting to the medical necessity of the surgery, her insurer said in a denial letter that it considered facial feminization procedures cosmetic. She picked up extra work as a software engineer, extended a line of credit and borrowed money from relatives to scrape together around $70,000 to pay out of pocket for facial feminization surgery in April 2016. Two years later, she is still trying to seek reimbursement – not just for her own wallet’s sake but to set a precedent so that paying out of pocket is no longer necessary.

“Even though it left me with more debt than I ever thought I would have, in retrospect, it was the best decision I ever made for myself; imagining my life without facial feminization surgery is the stuff of nightmares for me, yet that is the reality for the vast majority of trans women,” she said.

An Oregon graduate student who asked to remain anonymous said she chose her school in part because its health plan offered benefits for gender-affirming procedures. She still spent nearly a year going back and forth with her insurer to get pre-authorization for facial feminization surgery – even with her doctor’s endorsement of its medical necessity. Her provider finally agreed, but she said she still had to pay out of pocket because her surgeon required payment upfront. She sold her car and pulled money from retirement accounts to cover the $38,000 bill and then requested reimbursement – only to be denied again, documents show. Thanks to efforts of her graduate student labor union, the plan changed in 2018 to explicitly cover the procedure, and she was able to obtain reimbursement from her insurer.

Negotiating the insurance labyrinth

Being transgender is not a mental illness. It’s a state of identifying with a gender that differs from the sex you were assigned at birth. But for a transgender person to get coverage for gender-affirming care, they must often be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, a mental disorder.

Some contend that the diagnosis inappropriately pathologizes gender noncongruence and should be eliminated. Others argue that the diagnosis ensures access to care.

Initially, Jasmine thought the diagnosis would help her obtain coverage. Four years later, she says it has created barriers to treatment by stigmatizing her with a mental health diagnosis.

As soon as Jasmine found out that 12 months of hormone treatment was a prerequisite for genital surgery, she started therapy to confirm a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, she said, even though she didn’t have insurance at the time. Her therapist provided a letter for her physician, who prescribed her hormones. She started taking them in July 2012, paying for them out of pocket.

Her breasts grew to a C-cup size, and hair growth slowed on her arms and legs. She used hair regrowth treatment and her wispy orange hair grew past her shoulders and filled in her bald spots.

As her body started to change, she says, she experienced harassment over her appearance at work. She lost her job as a waitress in Grand Haven and could no longer afford to live on her own. In 2013, she moved into her parents’ home, also in Allendale.

Her experience is common. A leading survey of the American transgender population found that 30% of respondents who had a job in the previous year reported being fired, were denied a promotion or experienced some other form of mistreatment related to their gender identity.

The same survey by the National Center for Transgender Equality underscored the impact of stigma and discrimination on the health of people who identify as transgender. Thirty-nine percent of respondents said they experienced serious psychological distress in the month prior to completing the survey, and 40% had attempted suicide in their lifetime – nearly nine times the overall attempted suicide rate in the United States.

Much of that stress could be related to difficulties accessing health care, the survey authors said. One in four respondents experienced a problem in the past year related to insurance, such as being denied coverage for routine care because they were transgender. More than half of respondents who sought coverage for gender-affirming treatment were denied, and 25% of those who pursued hormone coverage in the past year were unsuccessful.

Insurance in the United States is a patchwork of policies that are regulated differently, depending on where and how they were purchased. Almost half of Americans get insurance through their employer, according to data analyzed by the Kaiser Family Foundation for 2016. The other half consists of those without insurance, those relying on Medicare, Medicaid, military plans or plans bought on the ACA market exchange.

The breakdown among the US transgender population is similar: According to the 2015 US Transgender Survey, 53% of respondents were insured through an employer-sponsored plan, 14% had plans they purchased directly from insurers or from health insurance marketplaces, 13% were insured through Medicaid, and 14% reported that they were uninsured.

Jasmine enrolled in a basic state-funded Medicaid plan through Priority Health in 2014. The first time she requested coverage for surgery, Priority sent her a denial letter.

“Sex change or transformation” was excluded from coverage, it said. “This exclusion applies despite any diagnosis of gender role or psychosexual orientation problems.”

She channeled her anger into researching laws and court rulings to fight the decision. By then, she had heard of Section 1557 and cited it in the appeal of her denial.

She called her condition “a significant disability that interferes with employment,” mirroring language in the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s standards and research on the effects of gender dysphoria.

After two reviews, Priority upheld the denial, citing the same exclusion.

Federal protection under 1557: A moving target

In 2015, when Jasmine sought coverage for surgery, federal rules may have technically been on her side – but there was ambiguity and room for interpretation. By then, a growing number of court decisions had interpreted federal laws against sex discrimination to apply to people who identify as transgender. And HHS had announced the proposed rule barring discrimination based on gender identity. But such an interpretation had not been codified in the ACA’s regulations.

Then, in May 2016, HHS’ Office of Civil Rights (OCR) issued a regulation explicitly stating that discrimination based on sex includes gender identity and sex stereotypes. The regulation applied to Medicaid, Medicare and private insurers offering plans on state marketplaces, forbidding them from excluding gender-affirming care from coverage.

The regulation did not tell insurers which services to offer. But it prohibited them from denying transgender patients equal access to coverage for medically necessary services available to other patients, such as mastectomies or prostate exams.

As of January 2017, all blanket exclusions were supposed to be removed from policies on the marketplace. But CNN found at least 19 policies offered in 2018 that still had blatant blanket exclusions.

When asked about the policies with blanket exclusions, some of the insurers offering them acknowledged that they should not be on the marketplace. Others said Section 1557’s regulations no longer applied to the plans because of the Franciscan Alliance lawsuit, a claim that experts dispute, suggesting that there is inertia and confusion about the state of the law that creates bureaucratic hurdles for transgender patients.

When CNN pointed out the exclusions to Health First, which offered eight of the 19 plans, it acknowledged that the plans on healthcare.gov were outdated. The carrier provided documentation showing that it has offered benefits for medically necessary transition-related services since 2017.

“We apologize for any confusion this administrative oversight has caused and we are committed to improving the health and well-being of all of our members and our community,” said Matthew Gerrell, senior vice president of consumer and retail services.

However, Gerrell also noted that his understanding was that 1557 did not apply to Health First policies because of the injunction in the Franciscan Alliance lawsuit.

Before 1557’s updated regulations could take effect for insurers in January 2017, a federal district court judge said the rule violated the federal religious freedom law. Texas District Judge Reed O’Connor issued a nationwide injunction preventing OCR from enforcing the gender identity provisions of the rule. On May 2, 2017, government lawyers won a stay to allow HHS to reconsider the rule’s “reasonableness, necessity, and efficacy” in light of the court’s injunction.

But the impact of that injunction varies depending on whom you ask. Interviews with a dozen stakeholders – lawyers, policy experts, state insurance commissioners and insurance company representatives – yielded different responses.

Gender identity discrimination is still impermissible under the statute, says former agency director Jocelyn Samuels, who oversaw 1557’s final implementation. She is now executive director of UCLA Law’s Williams Institute, a think tank dedicated to sexual orientation, gender identity law and public policy.

The injunction only bars OCR Rights from proactively enforcing the regulation, said Samuels, who served as director of the office from 2014 to early 2017.

But 1557 is still in place, she said. The statute builds on other longstanding federal civil rights laws, which interpreted sex to include gender identity. Even if the administration withdraws regulations protecting transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals – as the Departments of Education and Justice have done – they cannot undo years of case law and precedent, she said.

The injunction applies only to HHS enforcement, not private citizens, who can sue under the statute, Samuels said. In September, for example, a district court in California ruled in favor of a family that sued a San Diego hospital over the staff’s treatment of their transgender son, based in part on 1557.

While Section 1557 is in effect, insurers that receive any federal funding must ensure that all health plans comply with its anti-discrimination provisions, said Julie Mix McPeak, president of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The group has not taken a position on the injunction, leaving it to states to decide.

Representatives from two insurance companies said they did not offer transition-related benefits in states that did not include such services in their Essential Health Benefits, a set of 10 categories that insurers must cover under the ACA. They said state laws and mandates guide their policies.

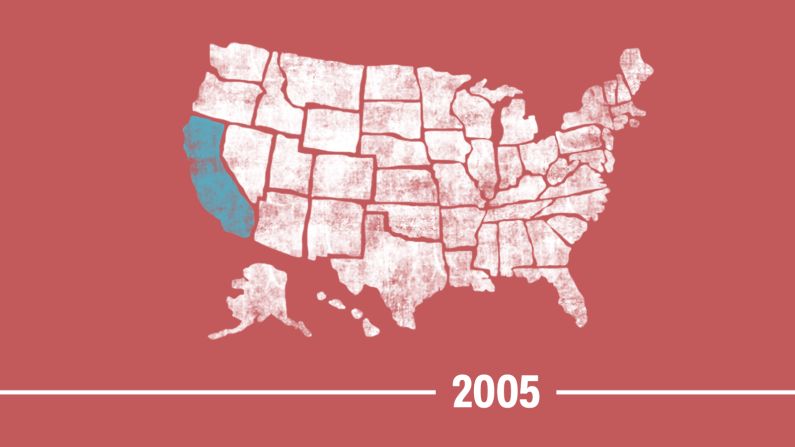

For example, Oscar Health offers plans with exclusions for gender-affirming care in Texas and Ohio, states without anti-discrimination policies that cover gender identity. When CNN contacted the insurer, its general counsel pointed out that its plan in California covers gender-affirming care, in compliance with the state’s anti-discrimination law and its Essential Health Benefits.

“Oscar believes that gender-affirming care, including gender reassignment services, should be considered an Essential Health Benefit and covered by all health insurers,” general counsel Bruce Gottlieb wrote in an email to CNN.

“Unfortunately, this is precisely the kind of issue that requires federal or state regulators to ensure that all insurers cover these services – otherwise, insurance markets will suffer from adverse selection,” Gottlieb wrote. “Oscar is proud to cover gender-affirming care in states that consider gender-affirming care an Essential Health Benefit, like California. And we are in constant conversation with regulators in other states to encourage them to mandate that all insurers cover these benefits.”

But a state’s Essential Health Benefits establish baseline requirements for benefits packages – not a ceiling, said Dick Cauchi, a health care policy analyst with the National Conference of State Legislatures. Even so, adding benefits can increase premiums, which can factor into negotiations with the state when developing benefits packages, he said.

Still, advocates say that’s beside the point when it comes to federally-funded plans. The ACA provides that, except where Congress has made explicit exemptions, all “health programs and activities” receiving federal funds, including insurance credits or subsidies, are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, national origin, age, disability or sex.

In other words, “a state cannot enable a provider or an insurer to opt out of nondiscrimination requirements that apply under federal law,” Samuel said.

‘Not medically necessary’

Jasmine tried again to get coverage for surgery in 2016, twice. She was denied, first based on the same exclusion and then because the surgeon was in another state.

The repeated crushing disappointments began to weigh on her. The stress exacerbated chronic pain in her muscles and turned her into a recluse, she said. She struggled to find a restaurant job despite her credentials: a culinary arts degree, a bachelor’s in hospitality and 15 years working in restaurants.

“To put it bluntly, it’s hard to get a job when you dress like a woman but look like a man,” she said.

After a friend helped her find work, she suffered regular panic attacks in the kitchen, a place she had once loved. She rambled on about her suicidal thoughts to her co-workers, unnerving them and eventually costing her the job, she said.

After long days working against the stiffness in her muscles, she went straight home and cried herself to sleep, she said. She spent her days off in bed, wary of the outside world. Strangers would “clock” her as trans and ask her questions, she said. Cashiers misgendered her and made her feel worse. She’s reluctant to go anywhere alone, including her favorite neighborhood sports bar, after encountering a drunk high school classmate who shouted derogatory names at her.

She missed her favorite holiday, Halloween, on the year she convinced her parents and sister to dress as superheroes for their annual group costume tradition. She would have gone as Harley Quinn, her favorite.

“I couldn’t do it. I was super stressed out,” she said.

Finally, in 2017, Priority agreed to cover her genital reconstruction. But she couldn’t get on the year-long wait list for surgery until she went through multiple rounds of hair removal.

Priority refused to cover that, as well as her request for surgery to make her facial features more typically feminine, saying that both were “cosmetic in nature and not medically necessary.”

Leading medical organizations in the United States agree that gender-affirming care is the most effective treatment for gender dysphoria. The American Medical Association and the American Psychiatric Association have issued position statements supporting coverage for medically necessary treatment as determined by a patient and their health care provider.

But to evaluate a procedure’s medical necessity, many insurers use criteria outlined in what’s known as the Stanford definition, Kristine Grow, senior vice president of communications at America’s Health Insurance Plans, wrote in an email.

Unlike the American Medical Association, the Stanford definition factors in “the cost-effective(ness) for this condition compared to alternative interventions, including no intervention.”

After Priority upheld denials for hair removal and facial surgery twice, Jasmine brought the case to Michigan’s Department of Insurance and Financial Services for external review.

In August 2017, a physician reviewer agreed that hair removal was medically necessary for her. But the reviewer upheld Priority’s denial for facial feminization surgery, citing insufficient literature to support a claim of medical necessity. Jasmine resubmitted her request for surgery and after Priority denied it, she appealed again. Earlier this month, a state administrative judge heard the case and sided with her. Priority has not yet responded to the decision, her lawyer said.

“We don’t want insurance companies determining our medical care, our treatment. We want doctors and professionals to make those decisions,” said Jay Kaplan, a staff attorney for the ACLU of Michigan’s LGBT Project.

“To be able to visually conform is part of her completing her transition. If not, she’s always regarded as ‘that trans person.’ And she’s encountered problems in her life because of that.”

‘A backdoor way of maintaining an exclusion’

CNN looked at more than 150 policies on HealthCare.gov. Most of them, rather than containing blatant exclusions, were limited or unclear on what gender-affirming care they might cover. Some policies offer “certain” transition-related services without specifying which. Other policies say they offer “gender reassignment surgery” and services related to gender dysphoria on one page, only to exclude services that authorities on transgender health recommend for treating gender dysphoria.

“We think this language is very problematic. We know that the way these exclusions operate in practice, ‘certain’ means ‘all we can get away with,’ ” said Kellan Baker, a health services researcher at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“This is a back-door way of maintaining an exclusion without having the kind of bald-faced exclusion that invites all but the laziest of regulators to intervene.”

The ambiguity leaves claims to be decided on a case-by-case basis that can stretch out for months – or even years, in cases such as Jasmine’s.

Dr. Tracy Kayan, who specializes in chest surgeries in Plymouth, Minnesota, said she tries to make the case for medical necessity by describing the impact of gender dysphoria on a patient’s daily life. A transgender man with extra breast tissue may experience anxiety when people call him a woman, discouraging him from interacting with others. Or people at the gym may stare at him as his breasts move around, causing him to avoid exercising.

Often, she said she finds the review process to be subjective, no matter what she says.

“If you asked two different physicians working for the same insurance company and doing peer-to-peer reviews for transgender pre-authorizations, I’m not sure if the approval would be the same,” she said.

“I honestly think a lot of what insurance companies approve is inconsistent and based on the personal biases of a single person, who could be an older, semi-retired family physician living in Texas who’s making a decision for a 19-year-old transgender patient living in Minneapolis who wants a breast reduction,” she said.

Dr. Joseph Silletti, chief of the urology division at Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center in New York, said he has met transgender patients who went for decades without surgery until insurance made it financially feasible.

“I’d see them in the recovery room crying, and they’d say, ‘You don’t know what this means to me,’ ” he said. “There is no faking that.”

Silletti started performing orchiectomies on transgender patients in 2013. The surgical procedure to remove one or both testicles helps with hormonal control. He said he saw an influx of transgender patients after New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced in 2014 the first of a series of measures preventing all insurers, including Medicaid, from discriminating against transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals.

“I couldn’t imagine living every day and waking up and wondering why I have the wrong organs,” Silletti said. “I just couldn’t. But these folks have been, and now I understand what a relief it must be to have the organs you believe you need, and I don’t see that as any way ‘cosmetic.’ “

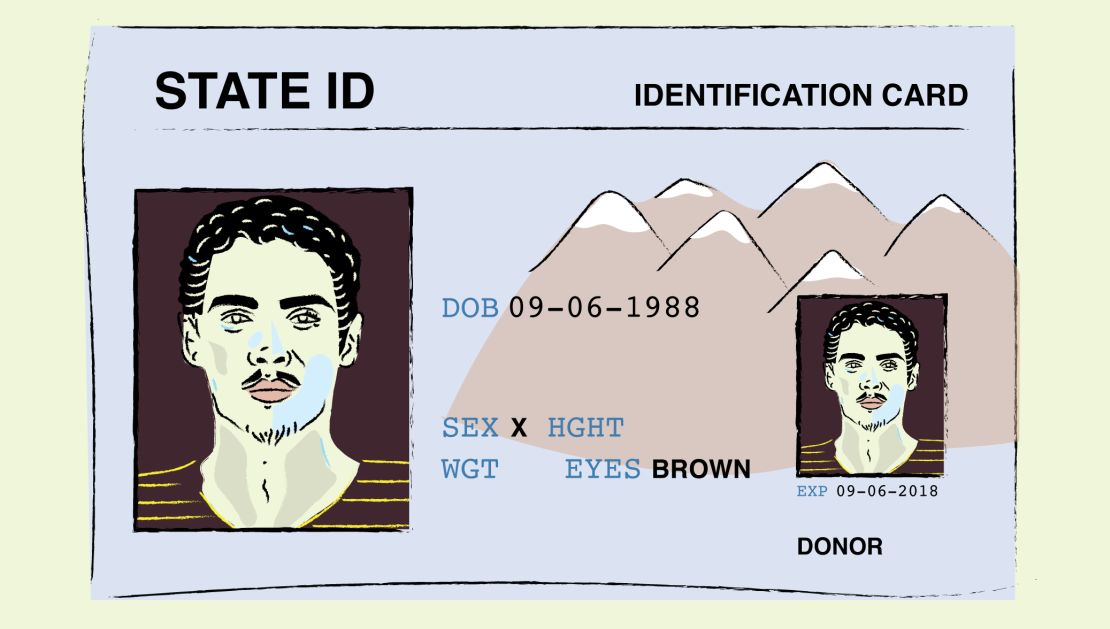

Because New York sets forth criteria for coverage of gender-affirming procedures, Silletti has found that getting surgery pre-authorization is typically easy, he said. The hard part is getting reimbursed due to an insurance coding issue, what he and other surgeons call the “gender mismatch denial” that occurs when an insurer will approve a certain procedure only for patients of one gender. That leads to denials when, say, a doctor seeks reimbursement for a transgender woman’s orchiectomy. This can cause problems for transgender or gender-nonconforming people who have not changed their gender marker on government-issued identification.

“The best way I can think to describe it is, in the pre-transgender world, we had two buckets you could live in,” he said. “We still have that, effectively, in computer systems.”

Kayan said she gets around gender mismatch denials through creative coding. She used to see frequent denials for transgender men seeking mastectomies, a surgery most commonly associated with breast cancer in women. Then, she began asking insurance companies to cover breast reductions – essentially, the same procedure – to treat gender dysphoria, and she saw fewer denials, she said.

Getting insurers to pay can be so complicated that some doctors preferred not to accept insurance at all. CNN reached out to 363 doctors listed on transhealthcare.org as offering transgender services. Of the 112 active surgeons who responded fully, 49% did not accept Medicaid, 38% did not accept Medicare, and 26% did not accept any form of insurance.

Dr. Beverly Fischer, a plastic surgeon in Baltimore, performed her first breast-reduction surgery for a transgender man in 1996. For years, her private practice was cash-pay only. As demand for gender-affirming procedures grew and more companies began to offer them in their health benefits, she started accepting insurance in 2012.

She said she stopped in 2017 because of the hassle.

“We spent so much time on the phone arguing, it became too much of a chore,” she said. “I got to point where I said, ‘I can’t run my business anymore.’ “

To be treated like any other woman

Jasmine is still waiting.

Each hurdle has stood in the way of a stable life and a job that makes the most of her culinary training. She would have preferred to spend the past few years managing a restaurant or a bar, the goal she was working toward before she came out. For now, she’s working at a fast-casual restaurant.

She wants to move on with her life. She wants to stop discussing her latest insurance grievance with friends. She wants to stop explaining her identity to customers looking for a “token trans friend,” she said.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

She wants to date and have a meaningful romantic relationship. She doesn’t want to be alone. She doesn’t want to go to another party and sit off to the side, fearful of starting something, only to have it end when a potential mate finds out that she has the wrong anatomy. She wants to meet someone with whom she can share her passion for “Batman,” “Star Wars” and Legos.

“Transness has monopolized my entire life, and that’s not OK. I just want to do the surgery and be treated like any other woman.”

CNN’s Braden Goyette contributed to this report.